Halet Çambel, architect of a lost Hittite city

Yonca Moralı ISTANBUL

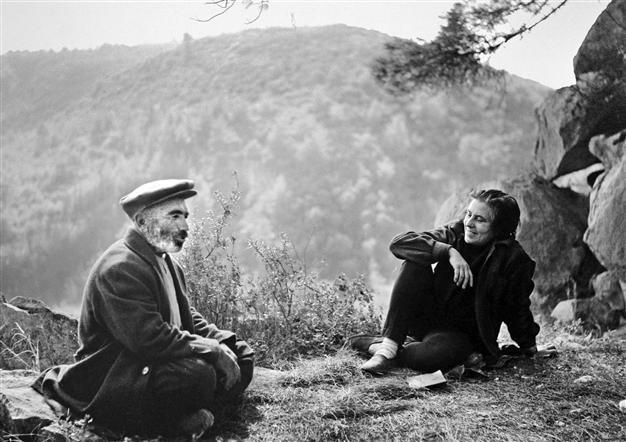

Halet Çambel, the sophisticated daughter of an elite Istanbul family, turned into ‘one of the locals’ of a Taurus village. DHA Photo

It is the 1936 Berlin Olympics. Atatürk moves boldly to expose the young republic’s proud and modernizing face to the world by appointing two women to represent the Republic of Turkey for the first time in the history of the competition. A 20-year-old archaeology student, Halet Çambel, is one of these two women accepting this prestigious assignment, in fencing. During the games, an invitation to meet Adolph Hitler is declined by the two young athletes. After completing, Çambel returns to her studies in Paris, unaware of the long and superbly inspirational life that lies ahead of her.

From this moment on, the legend of “Halet Abla,” or Sister Halet, began to blossom. In 1951, five years of excavations on the southern side of the Taurus Mountains overlooking the fertile Çukurova Plain by the mission team including Çambel had unveiled a Late Hittite Kingdom fortress dating from the 7th century B.C. The then leader of the archaeological mission decided to terminate the excavation works in what had come to be known as the “Karatepe-Aslantaş” historic site, in order to “shift efforts to a more significant location.” Çambel refused to follow the leader and accepted full responsibility for the development of the site, and thereby began a commitment that would continue until her last breath.

Thus the sophisticated daughter of an elite Istanbul family turned into “one of the locals” of a Taurus village - a place where there was no electricity, no running water, and where the only means of transportation was a mule.

AA Photo

Her passionate will to complete the fragmented puzzle of a lost Hittite city-state resulted in the discovery of one of the world’s most important historic sites. The site was defined as the frontier fortress of King Asativatas. A bilingual inscription carved on the basalt statue of the Thunder God allowed the complete deciphering of the Luwian hieroglyphic writing for the first time in history. This script declared King Asativatas as the protector of the “Adanava Plain” (the “Adana Plain” as called today) by appointment of the God of Fertility. Thus, a political ruler was made responsible by the gods for the wellbeing of his environment.

Open Air MuseumAn environment dominated by the Taurus Mountains, from which flow the Ceyhan and Seyhan Rivers, down through the fertile plain of Adana into the Mediterranean Sea; a magnificent geography as the main designer of civilization... Only towards the 21st century did the “cultural landscape” become the main focus of archaeology. But Halet Abla was ahead of her time in 1958, when she convinced authorities to declare the site a National Park, including 7715 hectares of land around the fortress, so that the historical site and its environment would be preserved as a whole. The “open air museum” model would then be implemented in other sites including Troy.

However, the relationship between historical sites and water is a doomed one, as growing energy needs invite gigantic dam projects. And a dam project was proposed for the Ceyhan River that would have inundated the lands surrounding the Karatepe-Aslantaş site, turning it into a little island. Once again, Halet Abla and her obstinate will intervened to save the Park. She studied the engineering plans for the dam for one year and developed a superb technical counter proposal. She

successfully convinced authorities to keep the water at a much lower level than originally predicated.

Halet Abla fearlessly tore down the barrier between archaeology, the environment, and human life. She touched the soul of the rural communities of the Taurus Mountains by including them into the development of the site. She expanded the minds of the inhabitants by teaching the local youth in various workshops. By reintroducing the forgotten tradition of naturally dyed kilims to the local women, she developed the local kilim sector as an important generator of income.

Maybe her passing should be seen as an opportunity to celebrate a generation of visionary “founders,” the first teachers of Turkey. These teachers brought hope wherever they went, empowering the community through the development of self-confidence, reconciling the “ruins” and the people through a newly found sense of pride and identity, in a cultural geography dating back to thousands of years ago…