İznik tile artists briefly paint the town red

NIKI GAMM

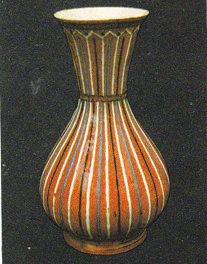

Not only did İznik tiles decorate architectural works in Istanbul, ceramic wares for daily use also found their way into the palace kitchen for such occasions as births, circumcisions and enthronement ceremonies and decorated the dining tables of the wealthy. Hürriyet photo

In the second half of the sixteenth century, there was a brief window of opportunity during which the ceramic workshops in İznik produced an extraordinary red color on their wares. The time frame was 1550 to 1580, at a point when the Ottoman Empire was at its peak, during its classical period. İznik as well as Kütahya had long been centers of tile-making because the clay soil in their vicinity was particularly suited to the production of ceramic wares. Wood was readily obtainable from the woods in the area. Neither of the two cities was very far from Istanbul and both were on commercial routes. Tile production was carried out in İznik in the Roman, Byzantine, Anatolian Seljuk and Beylik eras.

The period when İznik – and Kutahya tiles to some extent – reached its zenith is usually given as 1550 to 1580; however, some experts suggest this time frame stretched from 1540 to the end of the 17th century. The shorter frame coincides with support from the imperial palace in Istanbul. Tile designs were developed in the palace workshops, transferred to paper and sent to İznik for execution. Some of the most important architectural works of the Ottoman Empire were erected during this period thanks to the interest of Süleyman the Magnificent (r. 1520-1566) and the genius of Mimar Sinan (1490-1588).

Not only did İznik tiles decorate architectural works in Istanbul, ceramic wares for daily use found their way into the palace kitchen for such occasions as births, circumcisions and enthronement ceremonies and decorated the dining tables of the wealthy. In “Turkish Tiles” by Özlem Inay Ertem and Oğuz Ertem, the authors provide information on the palace kitchen register for 1582. “For Sultan Murad III’s son Şehzade Mehmed’s circumcision, it states that 541 İznik plates and cooking pans were purchased from the Istanbul market. Unfortunately most of the ceramics burned during the famous fires that were the greatest fear of Istanbulites and because of this, very few İznik ceramics have survived until now.”

İznik tiles were exported too and even filled orders received from abroad. The red İznik ceramics were popular in the Mediterranean and Near East, the Balkans and Europe, and some ceramics with inscriptions and coats of arms show they were made to order. The Ertems point out in their book that between 1865 and 1878, the Cluny Museum in Paris purchased 532 red İznik ceramics by means of the French consul in Rhodes and that these were displayed as Rhodes-Lindos ceramics. Some publications show İznik ceramics as Rhodes-Lindos ceramics and some misidentify them as Milet, Damascus or Haliç Work.

Producing İznik ‘red’

Producing İznik ‘red’During the classical period, the underglazing technique replaced earlier techniques and proved to be a success. The design, color and quality of the wares produced were superior to those before and after.

Once the clay had been moulded, the piece would be fired. After it cooled, to put the design on it, a pattern would be drawn on paper and then holes made with pins. This pattern would be put on the tile or ceramic piece and charcoal dust scattered over it. The pattern would be removed and painted, keeping to the outline left by the charcoal dust. Then a transparent glaze would be applied to the item and it would be fired again. This was called underglazing and was a relatively easy technique which led to stylistic changes in the motifs used. A more naturalistic style was used as the color palette increased. The Seljuks in Anatolia had favored turquoise, dark purple, blue and black but now under the Ottomans, green, red and light purple were added to the repertoire.

The most important of the changes was the addition of a particular red color that is either described as coral or tomato red or just İznik red. This begins to appear in the middle of the sixteenth century and is first used alongside the popular blue, white, turquoise and black in the interior decorations for Süleymaniye Mosque in Istanbul from 1550 and 1557.

The coral red was a discovery of the İznik tile workshops and its secret has never been solved although a British Museum website states that it comes from an iron-rich red earth, or bole, found in Armenia. This is entirely possible since a number of the tile-making workshops in İznik were owned by Armenians. The red produced a slightly raised texture and a dazzling color; it became the characteristic of the classical period. But its duration was short, approximately 40-50 years in total and no one was ever able to replicate the color again in spite of many attempts. This has led to speculation that the craftsman who discovered this color hid its secret and never related it to anyone before he died.

Exactly when the use of this red died out is in dispute with some experts saying it was produced until the beginning of the 17th century and others that it continued to the middle of that century.

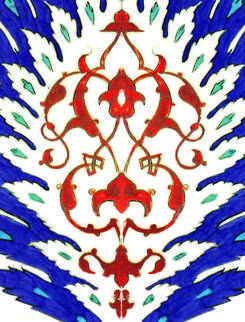

The motifs are clearly built on those of previous eras; however, they

are more naturalistic as the technique was relatively easy to use.

Thanks to the use of the pattern, the outlines of the images to be

colored were laid down in charcoal, and these were almost always traced

in blue and white or sometimes black. It is easy to identify the

flowers, branches, vines, trees, vases, bouquets, birds and animal

figures; however, grapes seem to be the only fruit images used although

apples were not unheard of.

Following the middle of the 17th century, İznik pottery declined and with it the red for which it was famous. The red was replaced with a dull brown and the backgrounds ceased to be the bright white it had previously been. The decline was in part due to the inability of the imperial palace to pay the high prices that had previously been asked. Orders were now placed for Kütahya ware that was markedly inferior. An attempt was made to revive tile-making at the beginning of the 18th century in Istanbul at the Tekfur Palace near Eyüp, but it gradually stopped production following the revolution of 1730 that saw the death of its patron, Nevşehirli Damad İbrahim Paşa.

Today we are fortunate in that there are many examples of red İznik tiles and ceramics in Turkey in the Topkapı Palace Tiled Kiosk, the Museum of Turkish and Islamic Art and the Sadberk Hanım Museum.

Abroad one can find examples in London, Oxford, Berlin, Paris, Washington, New York, Lisbon, Copenhagen, Athens, Hamburg and Cairo.

Producing İznik ‘red’

Producing İznik ‘red’ Following the middle of the 17th century, İznik pottery declined and with it the red for which it was famous. The red was replaced with a dull brown and the backgrounds ceased to be the bright white it had previously been. The decline was in part due to the inability of the imperial palace to pay the high prices that had previously been asked. Orders were now placed for Kütahya ware that was markedly inferior. An attempt was made to revive tile-making at the beginning of the 18th century in Istanbul at the Tekfur Palace near Eyüp, but it gradually stopped production following the revolution of 1730 that saw the death of its patron, Nevşehirli Damad İbrahim Paşa.

Following the middle of the 17th century, İznik pottery declined and with it the red for which it was famous. The red was replaced with a dull brown and the backgrounds ceased to be the bright white it had previously been. The decline was in part due to the inability of the imperial palace to pay the high prices that had previously been asked. Orders were now placed for Kütahya ware that was markedly inferior. An attempt was made to revive tile-making at the beginning of the 18th century in Istanbul at the Tekfur Palace near Eyüp, but it gradually stopped production following the revolution of 1730 that saw the death of its patron, Nevşehirli Damad İbrahim Paşa.