New regulations on minority schools causing confusion in Turkey

ISTANBUL- Hürriyet Daily News

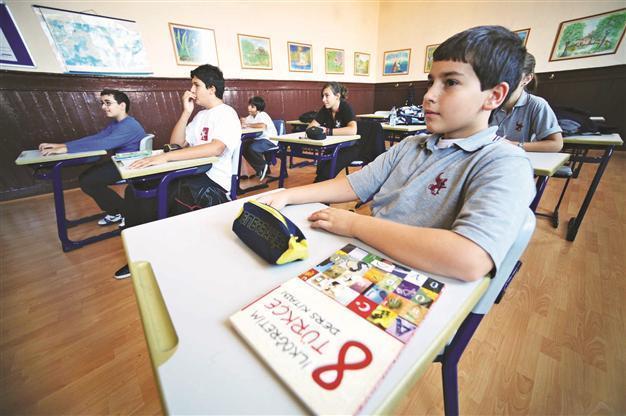

This file photo shows private Zoğrafyan School, one of the remaining Greek schools open in Istanbul. The regulations concerning private schools in Turkey and the 1923 Treaty of Lausanne allow only Turkish citizens to attend minority schools. DAILY NEWS photo, Emrah GÜREL

New regulations that came into effect on March 20 regarding

minority schools in

Turkey are causing confusion among educators, who claim the latest changes don’t solve the problems faced by the children of foreign nationals.

“We have [read] the regulations from top to bottom. Frankly we, too, remain perplexed,” Istanbul deputy education director Nedat İlhan told the Hürriyet Daily News.

The regulations concerning private schools in Turkey and the 1923 Treaty of Lausanne allow only for Turkish citizens to attend minority schools. A clause stipulating the children of Turkish citizens can attend only their own minority community’s schools was removed in the new regulations that appeared in the Official Gazette on March 20, however.

“The article was removed, but we are going to take a look at its infrastructure and whether it is applicable or not. Minorities in Turkey are classified under different titles in the Lausanne Treaty of 1923. As such, there is a critical question mark over here,” said İlhan, who is also in charge of affairs related to private schools in Istanbul, where all of Turkey’s minority schools are located.

Illegal immigrants

Some 15,000 Armenian citizens are currently residing in Turkey as illegal immigrants, according to the Armenian Foreign Ministry’s data. Their children cannot attend minority schools in Turkey both due to their illegal status and the terms of the Treaty of Lausanne. They were granted the status of “guest students” some two years ago, however, so they may now attend schools but cannot receive any diplomas or report cards.

“Even the children of ambassadors and officers from NATO-member Greece cannot receive diplomas from our schools with guest student status. The new regulations do not alleviate the problems concerning foreign nationals,” Yanni Demircioğlu, the headmaster of the historical Anatolian Greek Zoğrafyon High School in Istanbul, told the Daily News.

Some 70 “guest students” attend the Armenian and Anatolian Greek minority schools in Istanbul, although many illegal Armenian immigrants choose not to take advantage of the new “guest student” policy, as they prefer not to reveal their identities.

“Firstly, we are not a ‘private’ but a minority school. More importantly, special regulations have to be devised for each minority group. Different circumstances [apply to] Armenian and Anatolian Greek schools. These issues can only be set straight by provision of law,” Garo Paylan, a member of the Minority Schools Education Commission, told the Daily News.

“Minority schools have a quota

problem. Let us assume for a moment that a Syriac or a Protestant Armenian wants to attend a minority school. Then what is going to happen? We need to figure out what will happen to converts and examine the population data regarding minorities in Turkey,” İlhan said.

İlhan said Turkey has diplomatic relations with Greece but not with Armenia, and Armenian immigrants come to Turkey illegally. The children of illegal Armenian immigrants will still not be able to attend school regardless of the changes in regulations.

Another minority school director who spoke to the Daily News on condition of anonymity said they were disappointed by the lack of progress on the matter despite all the talks held with the government. He also expressed his frustration that the new regulations did not abolish the requirement for minority schools to have a Turkish deputy assistant.

“We wanted to determine [the deputy assistants’] term of service ourselves, but we are back to where we were five years ago, it seems,” he said.