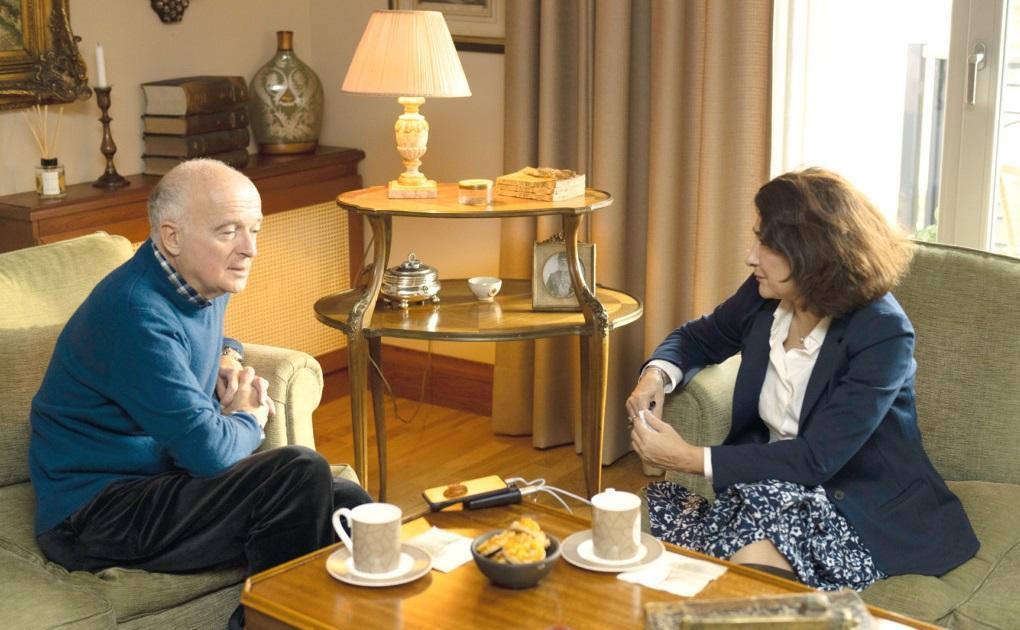

'In the 1990's, the European Commission was all-powerful, but 15 years later, when I went back as ambassador, things had changed completely,' says retired diplomat Selim Kuneralp (L).

The United Kingdom leaving the European Union is a bad decision for the British, the union, and everyone else including Turkey, according to a retired Turkish diplomat.

“The U.K. has traditionally been one of the most forceful supporters of Turkish integration with the EU,” Selim Kuneralp has told Hürriyet Daily News.

“Once the U.K. is out, France and Germany will dominate, and in an EU where France and Germany call the shots, clearly there is very little hope for Turkey’s accession,” he added.

What is your view on the new European Commission and its impact on the Turkish-European Union relations?

These days the commission is not as influential as it used to be.

I have had two postings in Brussels, once in the 1990s and the second time some 15 years later. In the 1990s, the commission was all-powerful, and when we were negotiating the Customs Union, we dealt essentially with the commission and very marginally with the member states and even less with the parliament.

To give you an example, when we were negotiating the Customs Union, some Mediterranean countries were creating difficulties over liberalizing Turkey’s exports of tomato paste. I suggested to the commission that we should approach member states. The reply was that keeping member states under control is the responsibility of the commission.

So, my interlocutor said, “You don’t need to worry about it, we will settle it,” and indeed, they did fall into line.

Also, as the parliament was consulted on the Customs Union, as Turkey we were rather worried that something might go wrong with the parliament. But the commission said, “They will be so happy that we are consulting them even though we are not legally obliged that they will vote in favor of the Customs Union.” Indeed, that’s what happened.

Fifteen years later, when I went back as ambassador, things had changed completely. I spent most of my time lobbying parliamentarians, the rest [of the] influential member states and once in a while going to visit my counterparts in the commission. The power had shifted from the commission to the member states and to the parliament.

And what does this tell us about the EU?

It tells us that the EU is gradually losing its supranational character and turning into an intergovernmental organization where the commission is gradually reduced to the status of the secretariat of an international organization like the WTO (World Trade Organization).

Would you say this would probably have a negative effect on Turkish – EU relations since the commission has usually been supportive of Turkey? Have we lost an ally?

We have lost an ally within the EU, but that is not exclusively because of the change of power structure within the EU. Things have changed in Turkey too as it is moving away from the criteria that are expected of a candidate. If you look at the reports from the commission, the word backsliding appears many times.

Yes, but in the past, when similar backslidings occurred, the commission would try to find the middle ground, whereas today we should perhaps no longer expect such a role from the commission.

But when the commission has indicated that Turkey is moving away from fulfilling the membership criteria, it has tied its hands. If it had said otherwise it would have lost its credibility.

The negotiations hit the wall already five to six years ago not just because of Turkey’s lack of progress, of course, but also because of Cyprus.

Even then the commission has recommended to deepen and broaden the Customs Union, that as well was blocked at that time by Cyprus. And currently, the member states and the parliament adopted a resolution stating that in present circumstances there could be no question of making progress in the negotiations on the Customs Union.

While you say that it’s like a secretariat, its current president said this is going to be a geopolitical commission. This sounds like more than a secretariat’s mission to me.

When I said secretariat, I just meant that it was getting closer towards that, gradually. Take the recent development: The commission has recommended that accession negotiations be opened with Albania and Macedonia. Macedonia has done everything that it was asked to do, and the commission was able to do nothing when [French President] Mr. [Emmanuel] Macron said “No.”

So, what should we understand of “We are going to be a geopolitical Commission?”

They have certain areas [where] they can exert pressure; they have a lot of authority on climate change, for instance. The commission is putting forward all sorts of highly revolutionary ideas, things that also have an impact on us. They are talking about a border tax, which means that if you are a country that has not taken necessary measures to reduce your emissions, the idea is that they will charge for polluting and creating unfair competition. The commission is preparing that, which will have an impact on our relationship as well.

But many believe the EU cannot take additional negative action against Turkey as it threatens to let the refugees go to Europe.

It’s the only argument that we have, that we will open the floodgates and let the refugees out.

Are we to frame this relationship to that simple equation: Turkey is holding the refugees while Europe maintains a limited cooperation? Are we bound to have this transactional relationship in the near future?

We already have a transactional relationship.

But the fact is that we are not doing anything in the area of the accession negotiations. Political dialogue has stopped. Even if we talk to each other, there is no commonality of purpose in the region — the Middle East, Mediterranean, Africa, Syria. So, the only thing left is the Syrian refugees. If Turkey was to open the floodgates and people started dying on the beaches and drowning in the Aegean, as they did three to four years ago; Turkey would be held responsible and its already bad image would further suffer.

The Turkish administration was somewhat enthusiastic about the prospect of Brexit in the hope that it might provide different types of membership. What is your view?

If that is the attitude, they are totally wrong. Brexit is bad for the British themselves, for the EU. It’s bad for everyone, including Turkey.

The U.K. has traditionally been one of the most forceful supporters of Turkish integration with the EU. Once the U.K. is out, France and Germany will dominate. In an EU where France and Germany call the shots, clearly there is very little hope for Turkey’s accession.

But some would argue, thanks to Brexit there could be a multi-speed Europe and that could benefit Turkey.

This idea of concentric circles has been on the table for more than 20 years, and it doesn’t work for the simple reason that if you want to create circles in the EU, who among the 27 will volunteer to be in the outer circle? And if you want to create this EU with different circles, everyone must agree, because anyone can veto that type of arrangement. Plus, how would you define these circles? Turkey is already in a circle - the customs union. You already have these different circles.

WHO IS SELİM KUNERALP?

- Born in 1951, Selim Kuneralp hs graduated from London School of Economics.

- He joined the Turkish Ministry of Foreign Affairs in 1973.

- He served as deputy permanent delegate to the European Union from 1995 to 1997 and as director-general for the EU in the ministry from 1998 to 2000.

- He was appointed as Ambassador to Sweden in 2000 and to Korea in 2005. He served again in the Permanent Delegation to the EU as an ambassador from 2009 to 2011.

- After serving as the Permanent Representative to the World Trade Organisation he worked as the chairman of the Energy Charter Conference from 2010 to 2013. He retired in 2014 but continued to work as deputy secretary-general of the Energy Charter from 2014 to 2016.

- In 2011 he was made Chevalier de la Légion d’honneur, a title given by France.