The man behind the illustrated Ottoman manuscripts: Seyyid Lokman

Niki Gamm

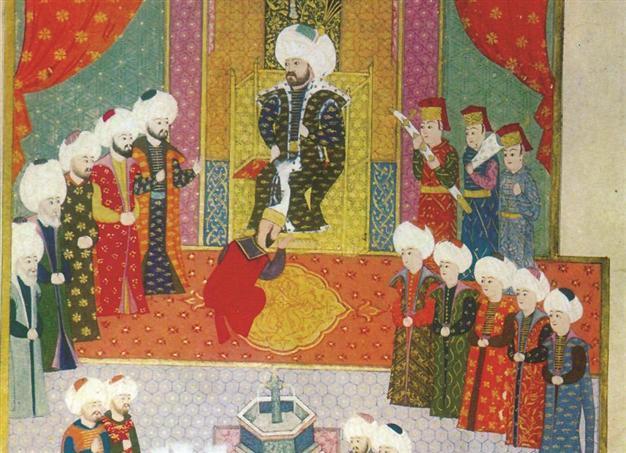

The Accession of Mehmed II in Edirne in the Hunarname by Lokman.

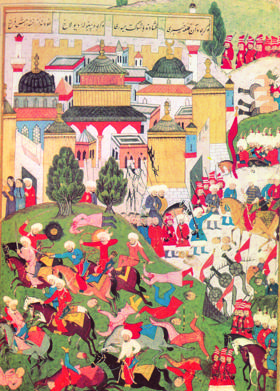

The miniatures from the classical Ottoman period are familiar for the most part, many of them produced and reproduced in books and magazines in Turkey, Europe and elsewhere. However, we usually forget that these were illustrations in manuscripts and little is reported about the contents of these manuscripts, let alone the authors of the books in which these miniatures originally appeared. These are the famous şahnames (court histories), of course, in which the exploits of the Ottoman sultans were described and praised.

The most important influence on Ottoman şahnames was derived from the great Shah-nama of Firdausi, a Persian poet who lived around the year 1000. His epic work, comprised of some 50-60,000 couplets, started with the creation of the world and ended with Persia’s being conquered by Arab armies during the expansive period of Islam in the seventh century A.D. Iran considers it the country’s national epic although it glorifies pre-Islamic times. Firdausi’s work served as the example par excellence for all future şahnames.

The first of the Ottoman writers of şahnames, known as şahnamecis (court historians), were Fethullah and Eflatun. Fethullah who was from Iran wrote poetry in Turkish as well as Persian in the time of Yavuz Sultan Selim (r. 1512-1520) and served as the şahnameci into the reign of Sultan Süleyman. He died in 1553 and in his place a man from Sirvan named Eflatun was appointed to be şahnameci. When he died in 1569/1570, the most prolific of all the şahnamecis in Ottoman times, Seyyid Lokman ibn Huseyin ibn al-Asuri al Urmevi, was appointed to replace him by Sultan Selim II. The sources are silent about his life and background or even how he came to the attention of the sultan.

Of the fifteen şahnames produced, ten were written and illustrated while Seyyid Lokman was the court historian. These were produced during the reigns of Sultans Suleyman, Selim II and Murad III that is from the mid-sixteenth century into the beginning of the seventeenth. Included are the Zafername from the last years of Süleyman, the Şahname-I Selim Han which is related to the sultanate of Selim II and the Sehinsehname that covers the first years of the reign of Murad III.

Historical events, hunting, moralty

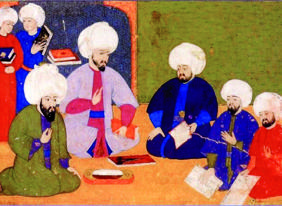

Historical events, hunting, moralty Actually we know as much if not more about the manuscript illustrators such as Nakkas Osman than we do about the writers. Nakkas Osman collaborated with Lokman on the Hunername (Book of Accomplishments) and the Zubtedu’t tevarih (The Cream of Histories). The Hunername starts with the Seljuks and continues to the end of the reign of Yavuz Sultan Selim with more than 500 pages in two volumes and 110 miniatures. In 1579 the first volume was started and in 1588 the second volume was finished. Not only did the Hunername cover historical events and victories achieved, but it provides information on hunting, customs, justice, charity and morality. Complimenting the writing are the miniatures which include historical events and aspects of Ottoman life on a background of architectural styles of the times. Seyyid Lokman’s Zubtedu’t tevarih is a history of the world up to that time and starts with the creation of the universe, continues with the lives of the prophets, the life of the Prophet Mohammed and the Muslim dynasties and concludes with the founding of the Ottoman Empire up to the time of Sultan Murad III.

Whether the post of court historian actually existed as a full-time, salaried position has been disputed, particularly by Emine Fetvaci who has examined archival materials into the day-to-day work of Seyyid Lokman. Nakkas Osman wasn’t the only artist with whom Seyyid Lokman collaborated. Each of the projects taken up had first to be approved by the sultan. Then it was a matter of selecting who was going to be part of project team which had to include the calligrapher, the artist or artists and even at times the person who prepared the gold ink that was used in the illustrations. Fetvaci makes a solid case for Lokman’s not just being the writer but his also being in charge of gathering the team and materials and ensuring that the group worked together. He kept a notebook in which he recorded salaries and even extra compensation. The records show also that he was authorized to bring in people to work on the manuscripts who weren’t regularly employed although there was a royal workshop. In addition, Fetvacı throws doubt on the idea that there actual was a physical workshop on or near Topkapı Palace that was used for the production of manuscripts.

Ottoman history written by chroniclers

Ottoman history written by chroniclersThe position of the şahnameci was discontinued after 1605 and the court historian changed. From then on, Ottoman history was written by chroniclers who recorded day-to-day occurrences. The sehname, even during Lokman’s tenure, changed. The original idea had been to publicize the Ottoman dynasty and its heroic sultans but the two sultans under whom Lokman worked never led the Ottoman armies to battle. As Fetvaci has pointed out, it is difficult to lionize a sultan who doesn’t behave like a lion. Her close examination of the illustrations revealed that more and more the courtiers became important and the sultan receded into the distance. That suits Lokman’s case. His initial patron had been Grand Vizier Mehmed Sokollu Paşa; however, he was assassinated in 1579. Lokman was left having to find a new patron but he seems never to have won over Koca Sinan Paşa who would become grand vizier in 1579 for the first of five times that he held the post. Between the death of Mehmed Sokollu Paşa and 1605 when the position apparently lapsed there were 25 grand viziers, including the five times for Koca Sinan Paşa. Lokman can hardly be blamed for not knowing to whom to turn.

After Seyyid Lokman, only two others were appointed to be şahnameci, one of whom, Talikizade Mehmed Subhi Efendi was a protégé of the same Koca Sinan Pasa whom Lokman had been courting. It must have been very disheartening for him but Talikizade, according to Ahmed Refik, chose to work with Lokman on the Tacuttevarih (The Crown of Histories) by Hoca Sadeddin Efendi. It was now the reign of Sultan Mehmed III (r. 1595-1603) who set forth in 1596 on campaign to fight the Austrians in Hungary. Talikizade and Lokman went with the army but the latter was ordered to return to Istanbul and finish the manuscript before the army got back. Presumably he did since the two men worked together for the next six years. In 1601 Seyyid Lokman was appointed to a treasury position and that’s the last we hear of him. But we still have the magnificent manuscripts he had a hand in producing.

Historical events, hunting, moralty

Historical events, hunting, moralty  Ottoman history written by chroniclers

Ottoman history written by chroniclers