Ottoman school for the gifted

NIKI GAMM Hürriyet Daily News

Boys selected to attend the Enderun would first live with specially chosen Turkish farmers so they could learn to speak Turkish and gain an understanding of religions and Turkish customs.

The Ottomans developed a school for gifted children long before the idea took hold in western European countries and through it supplied the Empire with civil and military leaders who kept the government together for better or worse until the end of the 19th century. This educational organization was known as the Enderun or the palace school.

The Enderun was first set up by Sultan Murad II, who reigned from 1421 to 1451, but was further developed under Fatih Sultan Mehmed II following the conquest of Constantinople in 1453 and the building of Topkapı Palace.

Basic education outside the palace started in the home with an emphasis on religion and morality. A boy would then go on to study at a medrese, a school usually attached to a mosque.

But the boys who were streamlined to enter the palace school were initially chosen from Christian families in what was called the devşirme. This practice involved choosing young boys – usually between the ages of 8 and 18 – from the Balkans who were good-looking, healthy and strong to be trained to be soldiers. This was something similar to what we would call conscription. Christian subjects were required to pay a tax in lieu of serving in the Ottoman army, but boys taken up through the devşirme became exempt from the tax. The devşirme was only applied according to need so it might occur once in three or four years. Later boys were chosen from families in Anatolia and eventually the system allowed Muslims to enter under pressure from those who had previously graduated and wanted their sons to have the same advantages.

Specially chosen Turkish farmersBoys selected to attend the Enderun would first live with specially chosen Turkish farmers so they could learn to speak Turkish and gain an understanding of religions and Turkish customs. After two to three years, these boys would be brought to Istanbul and examined. The brightest and handsomest would be sent to the palace for an education that was rigorous by any standards. The Enderun was located in the Third Courtyard of the palace and anyone who has visited that area knows that it is rather small. Because of this the boys were split and groups were sent to Galata, İbrahim Paşa, İskender Çelebi and Edirne palaces, where they would stay in barracks or dormitories in the Third Courtyard.

The boys would study Turkish, Arabic and the Quran and when they had a sufficient command of the two languages, they would be taught Persian. The latter language was important since Turkish poetry, one of the most important literary forms in the Empire, was based on Persian themes and meters. They would also have lessons in history, geography, geometry, astronomy inheritance law and calligraphy.

Sports were also emphasized and the sultans who had gone through a similarly rigorous education were fond of watching the boys at practice and at games. Weight lifting was an important part of the physical training and archery was particularly important although guns became the preferred weapon after the 15th century. Fighting with swords was also important and wrestling was another favorite sport that even some of the sultans indulged in during the earlier years of the Empire. Jerit, which is even played today, consisted of two teams challenging each other on horseback by throwing lances and then daring the opposite team to catch the challengers before they could return to their base line.

For the boys that showed an aptitude for music, there was extensive training in playing various instruments, singing and composing music. According to Albert Bobovi, a dragoman or translator, Turkish music was “a combination of the melody, the touch of the performer, and especially his ability to extemporize.” The women in the harem were also trained in music of lyric or instrumental sorts. Military music on the other hand was confined strictly to men to provide members for the Janissary military band that would accompany the army on a march.

The basic purpose for all of this training was to educate boys on how to serve in the palace and each of them, including the princes, would be taught a skill based on their specific talents and aptitudes. This skill was to provide a means for them to earn their living, if some mischance should occur. Such a skill might include fletching arrows or wrapping turbans.

The education was largely provided by members of the palace, but where it was deemed necessary teachers might be brought in from outside the palace. This was certainly the case where music instructors were concerned.

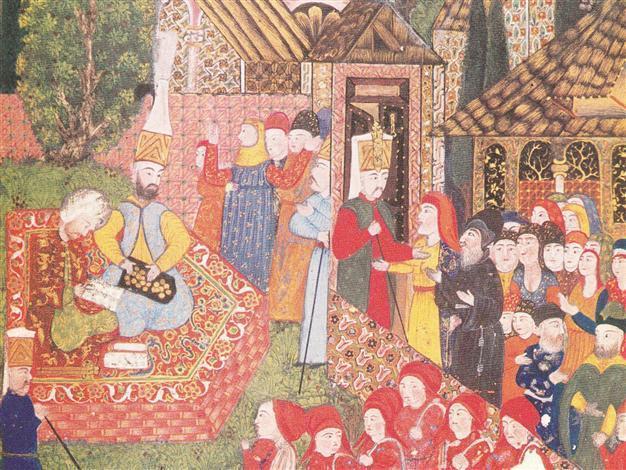

When the time came and their education was complete the boys would undergo a kind of graduation ceremony depending on which part of the seven different levels of the Enderun they had served in. Some would be assigned to the Janissary corps while others would be appointed to various posts in the government. If any of the boys failed to advance, they would be granted leave and assigned to positions in the army or outside the palace.

A bright future Ogier Ghiselin de Busbecq, the Austrian ambassador in the 16th century, wrote about the educational system of the Ottoman Empire and what kinds of men it produced. “No distinction is attached to birth among the Turks; the deference to be paid a man is measured by the position he holds in the public service. There is no fighting for precedence; a man’s place is marked out by the duties he discharges. In making his appointments the Sultan pays no regard to any pretensions on the score of wealth or rank, nor does he take into consideration recommendations or popularity; he considers each case on its own merits, and examines carefully into the character, ability, and disposition of the man whose promotion is in question. It is by merit that men rise in the service, a system which ensures that posts should be assigned only to the competent. Each man in Turkey carries in his own hand his ancestry and his position in life, which he may make or mar as he will.”

Indeed those who entered government service had a bright future before them. Depending on how ambitious they were, there was nothing to stop them from reaching as high as the position of grand vizier and indeed several of the boys raised in the Enderun actually reached that post.

Although the Enderun system declined it continued until the 19th century when Western styles of education were introduced into the Empire.