Ottoman activities in spring

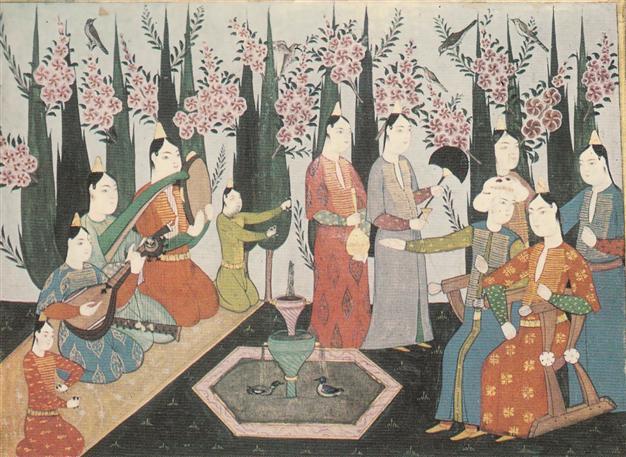

A 17th century harem evening.

The arrival of spring in Turkey is today celebrated by a spontaneous burst of activity in the outdoors, and the same was true among the Ottoman Turks. If you can, imagine the Bosphorus covered in green forest, mimosa, Judas trees and dotted with small villages that can only be reached by small boats. Even Beyoğlu was full of trees and gardens - ideal for picnics, a traditional pastime among the Ottomans.

PicnickingThe 17th century traveler Evliya Çelebi writes at one point how he and his friends used to go together when Ramadan came in spring and spend the nights eating and drinking (what they might have drunk he doesn’t say, although he always claimed that he didn’t imbibe alcoholic beverages. Sherbet perhaps?) The men would sing, play music and recite poetry. Elsewhere he adds, “there have been such amusements and pleasures on these green fields that no words can fully describe. All gentry, noblemen and prodigal sons of the plutocrats of Istanbul adorned the valley with more than 3,000 tents. Every night these tents were illuminated with thousands of candles, oil lamps and lanterns. In the evening the leading groups were entertained by musicians, singers, minstrels and performers … until sunrise while hundred thousand fireworks adorned the sky with lightning, stars, butterflies, etc., and the entire Kağıthane was bathed in this radiant splendor.”

In the 18th century, the wife of the British ambassador, Lady Mary Wortley Montague, wrote of their brief sojourn in Edirne as follows: “For some miles round Adrianople, the whole ground is laid out in gardens, and the banks of the rivers are set with rows of fruit-trees, under which all the most considerable Turks divert themselves every evening, not with walking, that is not one of their pleasures; but a set party of them chuse [sic.] out a green spot, where the shade is very thick, and, there they spread a carpet, on which they sit drinking their coffee, and are generally attended by some slave with a fine voice, or that plays on some instrument.”

Sultan Mehmed IV, the Hunter (Avcı), headed

for Edirne and the hunt.

HuntingHunting, on the other hand, was a sport limited to the sultans and top aristocrats, a sport undoubtedly brought with the Turks from Central Asia. One of the great tragedies during the establishment of the Ottoman Empire was the death of Süleyman Paşa, the eldest son of Sultan Orhan Gazi. According to tradition, he couldn’t resist hunting while laying siege to a town and died in an accident.

Mustafa Nuri Türkmen, in an article in Acta Turcica has pointed out that a sultan embarking on a campaign to hunt set off in much the same way he would leave Istanbul on military campaigns with great pomp and ceremony and a large entourage. Actually he was referring to Sultan Mehmed IV, nicknamed the Hunter (Avcı) because of his passion for the sport. We are fortunate to have a series of miniatures commissioned by the Swedish ambassador of the time (1657-58) which depicts such a departure and, although it is thought that these show the sultan leaving for Edirne in September, it would have been no different if it had occurred in spring.

According to the ambassador’s notes, several hundred people took part in the procession. In an article on the paintings, Swedish historian Karin Adahl points out that “the figures and horses are painted in a naïve and stylized manner and are highly stereotyped … The men are short and plump. They may be distinguished by their different uniforms and costumes and particularly elaborate headgears, as well as the distinguishing attributes that indicate the functions of the officials.”(K. Adahl, “The Departure to Edirne: Ralamb’s twenty paintings of the Sultan’s procession”)

Edirne was the favorite place for hunting, although other areas around Anatolia were preserved for the sultan’s pastime. After the first quarter of the 18th century however, the sultans no longer went to Edirne. Instead they hunted on the estates of their various palaces around Istanbul and these were kept stocked for their pleasure.

Ottoman army departing for campaign. 17th century.

“Distant Neighbor Close Memories” exhibit, Sabancı

Museum.

CampaigningThe third most important activity among the Ottomans in spring was the mobilization of the army. They had a system by which they didn’t have to finance a standing army and could provide a livelihood for its soldiers. According to Gibb and Bowen, “It [the system] involved, as in Europe, the grant of land to these soldiers. In return they were bound to do military service when called upon, and for this purpose to equip and mount not only themselves, but also, usually, a number of retainers varying with the size of each holding.” The total number of soldiers available at any one time during the height of the empire has been estimated at 140,000 to 150,000 men. Some Ottoman sources have a tendency to exaggerate these figures.

After the decision was taken to go to war and where, a call would be sent out to meet in Üsküdar if the army was to fight on the eastern front with Iran or in Edirne if the campaign was to advance into the Balkans. But this wasn’t just the collection of soldiers, enormous amounts of weapons and provisions traveled with the army. Several thousand tents were required and double the number because advance troops would be setting one a new base ahead while the old one was being taken down behind.

“It was a cold, wet day in Edirne. Though it was the 7th of May (9 M 1083), it was raining and snowing all the time, and there were sheets of ice on the ground. The Ottoman army was getting ready to leave on an expedition against Poland. The military encampment at Çukurçayırı, just outside the city, had been set up in late March, and the soldiers who had been living there ever since must have already been feeling worn out.” (Tülay Artan, The Departure Procession of 1672: Ottoman Antiquarianism or a Puritan Statement in “Distant Neighbor Close Memories.” The Balkans and Turkey were still in the grip of the Little Ice Age in 1672, when even the Golden Horn and the Bosphorus in Istanbul were blocked by ice. But marching orders were marching orders and the campaign had to begin.