Turkey does not have a growth story

Second quarter Gross Domestic Product (GDP), which was released on Sep. 10,

disappointed big time: At 2.1 percent, annual growth turned out to be much lower than expectations of 2.8 percent. After adjusting for working days and seasonality, the Turkish economy contracted 0.5 percent quarterly - its first contraction since the first quarter of 2012.

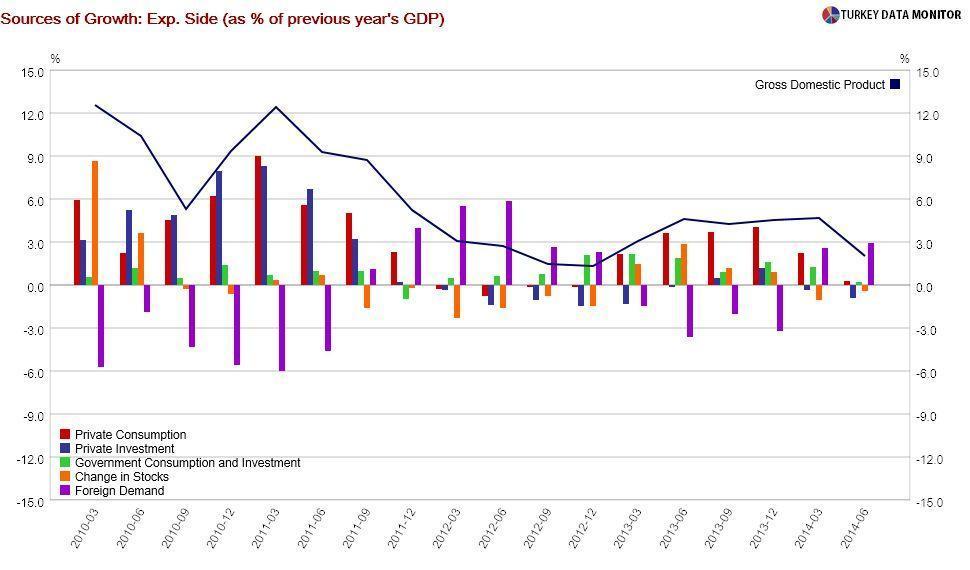

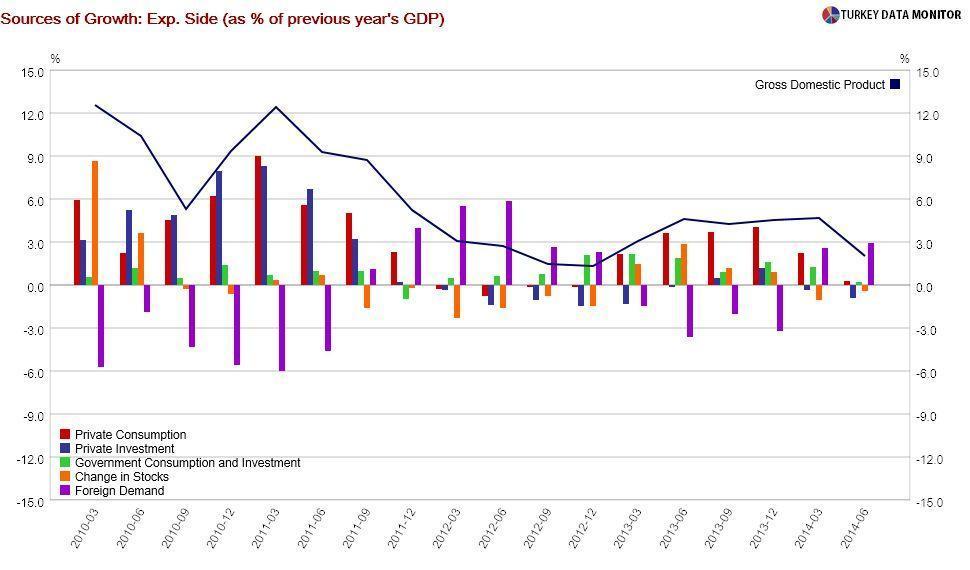

Looking at the details of the data, one can see that there is no single component of GDP that has caused the growth collapse: On a quarterly basis, private consumption and investment, public consumption and investment and exports all fell. Annually, almost all the growth came from foreign demand.

According to

According to Finance Minister Mehmet “

Nominal” Şimşek, “Turkey’s growth lost some momentum in the second quarter due to the impact of monetary tightening, the delayed effects of macro prudential measures, economic problems in EU countries and geopolitical tensions.” This statement is a typical case of concentrating on the trees at the expense of the forest. Simply put, Turkey just does not have a growth story.

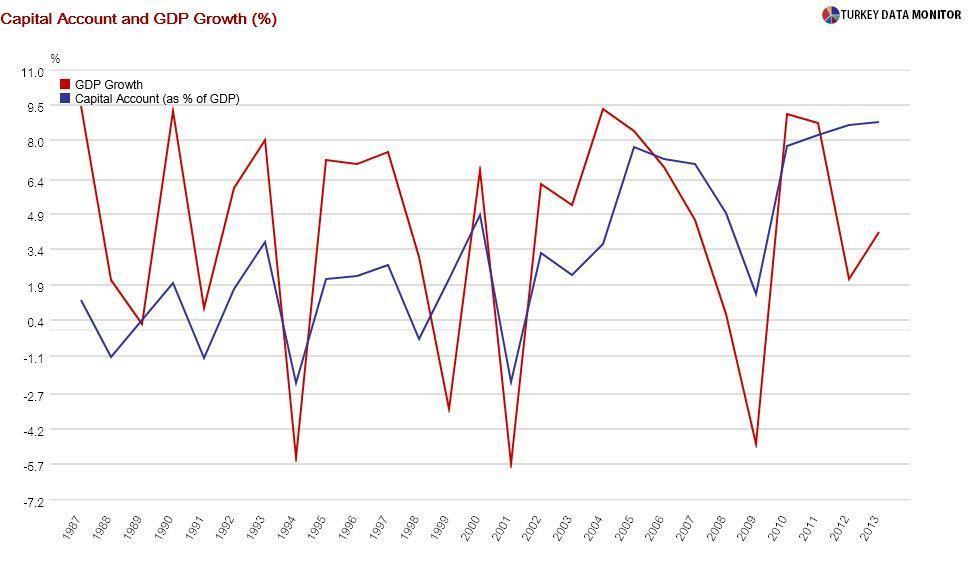

Actually, it has not had a proper one for several years, but it is only now that the country is starting to feel its bite: In the first half of the last decade, Turkey’s economic story was one of macroeconomic stability, combined with ample liquidity to emerging markets (EMs). The macroeconomic reforms were not followed by microeconomic ones, and the story became one of hot money supporting growth.

This story will keep getting retold so long as the money keeps

rolling in. For example, investment bank JP Morgan’s latest report was titled “EM carry gets extended lease on life.” They noted that “prospects of European Central Bank quantitative expansion” would keep investors borrowing in low-yielding currencies to invest in high-yielding ones like Turkish government bonds - the so-called carry trade. Since Turkey is one of the countries most attractive for this strategy, I was not surprised when JP’s regional report was titled “raise Turkey to overweight after ECB QE.”

Even though Turkey may become the darling of hot money again for a while, the fact remains that its growth model is based solely on capital flow-financed domestic consumption. Therefore, I would not be too optimistic on the robust third quarter leading indicators like this week’s industrial production, which I correctly forecasted in my

last column, by the way.

Back-of-the-envelope calculations reveal that Turkey would need to grow at least 3-3.5 percent to keep unemployment at bay. And as the U.S. hit show Seinfeld’s unforgettable Cosmo Kramer

once remarked, “when there’s no work, and the people get restless, who do you think they come after? El Presidente!”

So if economy czar Ali Babacan can convince President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan that Turkey cannot grow without structural reforms, he may revive

the country’s long-forgotten reform agenda and try to write a new growth story. Otherwise, Turkey is bound to stay in the

middle income trap forever.

Second quarter Gross Domestic Product (GDP), which was released on Sep. 10, disappointed big time: At 2.1 percent, annual growth turned out to be much lower than expectations of 2.8 percent. After adjusting for working days and seasonality, the Turkish economy contracted 0.5 percent quarterly - its first contraction since the first quarter of 2012.

Second quarter Gross Domestic Product (GDP), which was released on Sep. 10, disappointed big time: At 2.1 percent, annual growth turned out to be much lower than expectations of 2.8 percent. After adjusting for working days and seasonality, the Turkish economy contracted 0.5 percent quarterly - its first contraction since the first quarter of 2012.