Embroidering Ottoman Culture

NIKI GAMM Hürriyet Daily News

The fame of Turkish embroidery spread well beyond the confines of the empire and was much admired in Europe. Especially in the Balkan region, which adjoined the empire, Turkish embroideries greatly influenced colors and motifs.

Decorating materials is an art that long predates historical records. Fabric does not hold up well. Embroidery requires fabric, needle, thread, an embroidery frame and beyond that, a patient woman to ply the needle, good eyesight and free time.

Most historians believe that embroidery was first practiced in China or possibly India, and both countries were famous early on for their skillfully done work. The Turks of Central Asia were also known for being good embroiderers and undoubtedly brought their patterns with them as they traveled westward but they certainly weren’t the first to do this work in the eastern Mediterranean. The veil made for the Holy of Holies among the Jews was of fine linen, embroidered with “cherubim of blue and purple and scarlet.” Homer, in the Iliad, writes the beautiful Helen, sitting in her palace in Troy, would embroider the exploits of the Greeks and Trojans in their famed war.

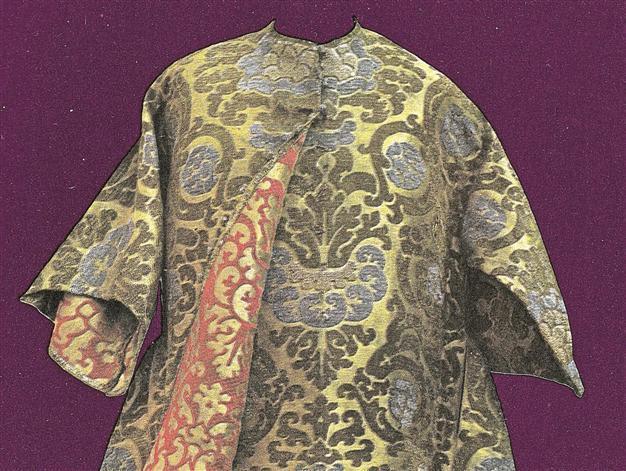

The Byzantines were given to elaborate gold embroidery on their gowns, if one can judge from the various frescos and mosaics that still exist from that period. Emperors and religious dignitaries alike are portrayed in long robes with extensive designs in gold. A favorite design was that of two birds or animals facing each other with a tree of life in the middle. The style was taken up in the extensive embroidery produced on behalf of the church in Europe. It was so highly regarded that special rooms were set aside in monasteries and convents where men and women would respectively embroider.

Decorating textiles

Among the Turks, embroidery has been very important. It served to decorate textiles associated with handicrafts such as wool, linen, cotton, silk and even leather. These products ranged from household goods and clothing to horse harnesses. Most likely the women would do much of this work during the winter when many of their usual pursuits would come to a halt. When they migrated into the Middle East and then Anatolia, they added materials like velvet to their repertoire and, as a result of their conversion to Islam, their motifs emphasized floral designs rather than animal patterns.

The importance of dyeing threads for use in embroidery cannot be emphasized enough. For millennia, this process relied on experimentation and finding the right plants and minerals needed to produce the desired colors. Vegetable dyes produce vivid but natural colors and maintain their brightness unless of course the end product is left in the sun and fades. Among the possibilities are the bark of the walnut tree, the leaves of the plane tree or the peach tree, the onion plant, insect shells and various flowers such as roses and lilies. The basic colors are “red, yellow, brown, grey, purple, mauve and black together with various shades.” The Turks almost certainly learned how to use gold and silver thread after they entered the area. In the 19th century, chemical dyes were introduced into Ottoman embroidery and produced a different variety of colors. Towels, sheets, napkins, kerchiefs, handkerchiefs, bags, cushions, quivers, curtains, tents, clothing right down to underwear and more were embroidered. The quality of the material would reveal the social class. The finest work was done in and for the imperial palace and we are fortunate in having hundreds of items preserved there. It was the custom whenever a sultan died to bundle up his clothing and store it.

Differences between regionsAyten Sürür, in her book “Türk Işleme Sanatı,” notes that there was a great distance between the work being produced by the palace and that done by peasants. As well, there are differences between regions. That is hardly surprising since a workshop was set up inside Topkapı Palace itself and the best craftsmen around the empire were brought there to work. Following the conquest of Constantinople, Fatih Sultan Mehmed II set about repopulating the city and offered, among other things, property to artisans who were willing to come and settle there. During the height of the empire in the 16th century, the most typical motifs were the tulip and carnation. The fame of Turkish embroidery spread well beyond the confines of the empire and was much admired in Europe. Especially in the Balkan region, which adjoined the empire, Turkish embroideries greatly influenced colors and motifs. Embroidered kaftans and other costumes were sought after and many a portrait was painted with the subject wearing Ottoman clothes. When the Industrial Revolution arose, some kinds of embroidery could be produced by machine and therefore more cheaply than by hand. The adoption of Western forms of dress also contributed to falling interest in embroidery until today, when it is more of a handicraft that few engage in, except as a hobby. It is expected though that examples will be shown at the Handicrafts Fair in Beyoğlu’s Tepebaşı grounds this coming week.