Ever since the advent of the neo-liberal agenda in the early 1980s, privatization has been presented as a panacea for all economic problems. Proponents have consistently talked about the benefits of reducing government size and personnel to ease the burden on national budgets and improve the overall economy. Neo-liberals were convinced by the free market efficiency and gave no credit to other points of view. Neither were they overly concerned about such issues as equality, public good, the importance of the state in maintaining social cohesion, or national security.

But the 2008 crisis clearly showed that, in a deregulated context, extreme neo-liberalist measures cannot deliver on its promises. We all witnessed the acute economic austerity and social misery that crisis created. And now recent talk of returning the U.K.’s privatized services back to the public shows the end of the age of extreme privatization is drawing near.

As we all know, the U.K. followed a pioneering privatization policy back in the 1980s under then Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher. However, according to a January 2018 article by the Guardian’s Will Hutton, polls show an astonishing 83 percent in favor of nationalizing water, 77 percent for electricity and gas, and 76 percent for rail. With the upcoming elections and prospect of a Labour government, the U.K. is likely to become an economic lab for the whole world. Indeed, the tide seems to be turning.

In Turkey, governments have also followed a comprehensive privatization policy since the early 1990s. Strictly following the IMF recommendations, privatization was always an economic policy priority. State-Owned Enterprises (KITs in Turkish) were seen as a drain on the country’s finances and were therefore sold at attractive prices to local and international buyers.

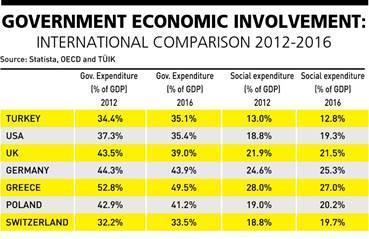

While we cannot retroactively judge the validity of these policies, we can study current conditions and the extent of government involvement in the economy using available measures like government expenditure (a percentage of the GDP) and social expenditure (a percentage the of GDP).

The first observation is that total government expenditure in Turkey stands at a modest percentage of the GDP. Turkey has a similar level of government expenditure to traditionally free-market countries such as the U.S. and Switzerland. It has much lower levels than Germany and Poland, which emphasize state involvement in achieving social cohesion. Such low government expenditure in Turkey can partly be attributed to the last decades’ extensive privatization programs.

Secondly, social expenditure levels are much lower than those of other countries included in the table. Clearly, there are many social and historical differences between them. For example, Germany’s social state approach offers generous unemployment and health benefits. Similarly, Poland emphasizes old age and child-care plans. In contrast, Turkey has kept its social spending levels under strict control. Needless to say, here, we are not recommending drastic government expenditure increases. However, we argue that Turkey can comfortably allocate more resources to social spending. In fact, Turkey could allocate more social resources to programs that promote female participation in the workforce. This would be a clever move because Turkey can do more to integrate them into active labor force. Following the Polish and Dutch examples, Turkey could also take steps toward having more flexible childcare programs for working mothers.

Since Turkey’s economy is currently going through turbulent times and there is pessimism from some macroeconomists certain circles are likely to push for more privatization and austerity programs. However, this short article aims to show that Turkey has already rolled back the state a lot and that further cuts to government spending will not have the desired effects. In fact, more state leadership in terms of social programs (labor force quality) and technological development (entrepreneurial state) are both appropriate and timely for the long-term benefit of the country. With regards to the privatization, the tide has turned.