Turkish cinema digs deep into recent history

Emrah GÜLER ANKARA - Hürriyet Daily News

Two new Turkish films ‘Qüfür’ and ‘Hile Yolu’ (Deception) both released this week, are deeply influenced by the whole history of Feb. 28, 1997 and its aftermath up to one-and-a-half-decades later.

The repercussions of the Feb. 28 process, or the “postmodern” coup as referred to by many, continue to define the political, social, educational, and even the artistic atmosphere in today’s Turkey. The process took its name from a meeting of the National Security Council on Feb. 28, 1997, a time when the military had more power than the elected government.

Following the infamous meeting, the military issued a memorandum imposing decisions to cement the secularist ideology in the face of a perceived threat by the rising Islamist ideology. The prime minister, Necmettin Erbakan of the Welfare Party, and the coalition government, was forced to sign a set of decisions, some of which banned the headscarf in the universities, shut down Quranic schools, abolished the Sufi orders, and raised the total amount of compulsory education to eight years.

The Feb. 28 process eventually led to the resignation of Erbakan and his coalition government after just one year in office. The government was forced out without dissolving the Parliament or suspending the Constitution, hence the name “postmodern” coup. The process since then has fuelled a polarization between conservative Islamists and secularists that is visible not only in political power games but in everyday life, which has come to define the dynamics of 21st century Turkey.

Two new Turkish films, both released this week, are deeply influenced by the whole history of Feb. 28, 1997 and its aftermath up to one-and-a-half-decades later.

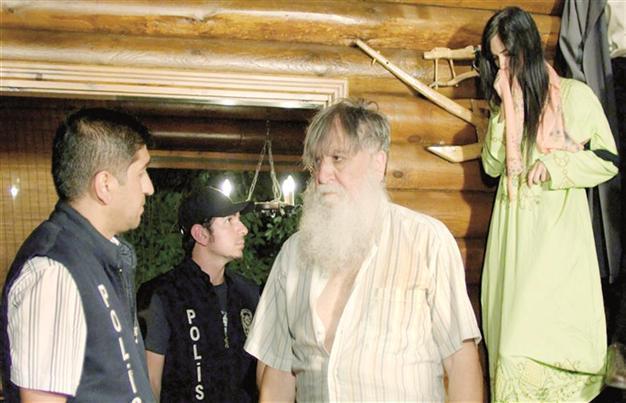

Müslüm Gündüz and Fadime Şahin were the actors of a national scandal in late 1996, whose names became symbols in the lead up to the Feb. 28 process. Gündüz was the devoted anti-secularist leader of the Aczmendi community, a self-proclaimed Islamic order. He was arrested by the police in December 1996 in a house where he was found with Şahin, a 22-year-old female student, which led to an investigation in which it was alleged that she was being shared sexually among the leaders of the community.

Confronting recent history in Turkish cinema

The scandal is the obvious inspiration for one of this week’s new releases, “Qüfür.” At the center of the movie, co-directed by Mustafa Delazy and Arafat Şavata, is an Islamic sect whose leaders and male members find Islam to be the best medium of exploitation for their personal aggrandizement, taking in some unsuspecting - and others not so unsuspecting - young women to be their blissful and blessed companions.

The movie begins with the leader of the sect, the faux-sheikh Limon Hodja, finding himself a much younger woman, promising her family a place in heaven in exchange for her hand (and more). However, the Hodja’s unexpected death triggers a chain of events within the sect to replace him - mostly the lowest form of power games. In the midst of all the brouhaha, young love blossoms. The young couple trying to run away from the sect operate as an antithesis to the false leaders abusing Islam for money, power and sex.

Murders of ArmeniansAnother new release, director and writer Ersin Kana’s “Hile Yolu” (By Way Of By Way Of Deception), takes us to another secret organization, a sleeper cell targeting non-Muslim minorities. The recent series of murders of Armenian women in Istanbul is one of the many darker corners of Turkey’s recent history that serves as an inspiration to the movie.

Albeit half-heartedly, the film looks at the intricate dynamics among the organization, the police and the deep state, working more as a crime drama than a political one. “Hile Yolu” focuses on the story by looking into the relationships among its leading characters, the trigger-happy young men, who have been fed with hate and a sense of manufactured accomplishment in order to fill the void created by polarization, lack of education, and unemployment.

A missing hard drive at the heart of the story turns out to contain crucial information on the murder of Turkish-Armenian editor and journalist Hrant Dink in 2007, and on the Ergenekon investigation, an operation into an alleged organization consisting mostly of military forces planning to overthrow the government, and to many, a revenge operation for the Feb. 28’s postmodern coup. While touching on many grave matters in Turkey’s recent history, the film uses them merely as a backdrop for its crime story. “Qüfür” and “Hile Yolu” may only be average, for different reasons, for both box-office audiences and art-house lovers. Still, the two films hint at a new direction Turkish cinema is taking, confronting the very recent history and its repercussions.