The unraveling of the old order in the Middle East

William Armstrong - william.armstrong@hdn.com.tr

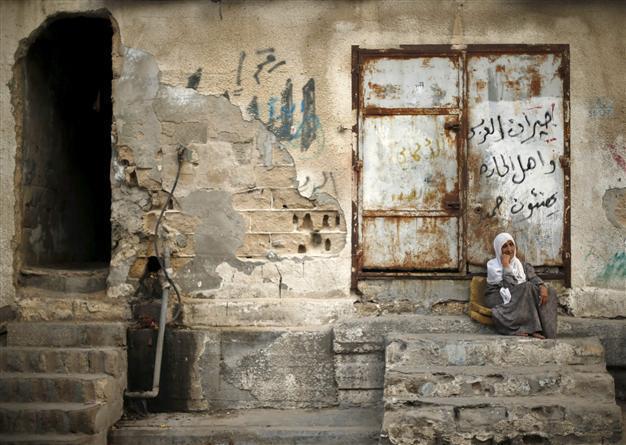

A Palestinian woman sits outside her house as she escapes the heat during a power cut at Shatti (beach) refugee camp in Gaza City, Sept. 15, 2015. Reuters Photo

‘Shifting Sands: The Unraveling of the Old Order in the Middle East’ edited by Raja Shehadeh and Penny Johnson (Profile, 208 pages, £10)The American novelist William Faulkner wrote that “the past is never dead. It’s not even past.” This collection of essays on a Middle East in meltdown agrees, constantly returning to the seismic events 100 years ago when the

Ottoman Empire collapsed during the First World War. A century on, the ambiguous order born of that collapse is now violently unraveling, but what will replace it is far from clear.

As British-Israeli historian Avi Shlaim writes in the opening piece, “The post-1918 peace settlement is at the very heart of the current conflicts between the Arabs and Israel, between Arabs and other Arabs, between some Arabs and the West.” Many believed that this “post-Ottoman syndrome” was coming to an end when the first optimistic green shoots of Arab protest broke through in late 2010, but since then the situation has drastically deteriorated. Authoritarian regimes have fought back and swathes of the region have been engulfed by sectarian bloodshed. In the words of Egyptian historian Khaled Fahmy, debate now centers on the question: “How did the Arab Spring morph into an Arab nightmare?”

This volume was inspired by a series of panels seeking answers to that question at the 2014 Edinburgh International Book Festival. It is far from comprehensive, but despite its relatively short length the book is diverse and has plenty of insight from an A-list line-up. No shortage of ink is spilled on these questions elsewhere; at its best “Shifting Sands” offers a bracing fresh look.

But although it sweeps impressively, the contributors’ insistent return to the colonial question often feels like a substitute for answering more complicated questions. In a great metaphor, journalist and historian Justin Marozzi likens the Western powers in World War One to “quarrelling dinosaurs”: “As they fought in Europe, their long tails would sweep across the Middle East, destroying countries, remaking borders and creating new facts on the ground that the local population then had to live with.” We certainly should not downplay the cataclysmic effect of Western imperial policy in the region. The problem is that this gives us no alternative for how we think about today.

In the final essay, editor Raja Shehadeh writes that “The Middle East is not meant to be fragmented. As the essays in this book have shown, this was the doing of the colonial powers after the First World War.” That is a crude over-simplification. Claims about some halcyon era of unity are ahistorical and often ideologically motivated; the region has always been fragmented and host to violent local divisions. It is fashionable to describe various states in the Middle East as “artificial,” as if nations elsewhere are somehow more “authentic” and not similarly artificial formations. Plenty of non-Western states are colonial creations and plenty had native elites coopted by imperial powers, which some observers claim lies at the root of the Middle East’s current strife. But few are ripped apart by such apocalyptic unrest. For all the self-flattering talk of Anglo-French pens blithely drawing “lines in the sand” to mark borders, modern Iraq and Syria are not historical abominations. Both are coherent historical entities with references in the history books going back millennia.

Anyway, what is the alternative? Boundaries are clearly being de facto redrawn today, but should the aim really be a more “ethnically aligned” order? Should ethnicity or religion be promoted as the determining factor of any state? That would not only be morally dubious, it would also mean population movements on an even vaster scale - with plenty of bloody precedents from the past century. Alternatively, perhaps unsustainable mini-states should be subsumed under some kind of larger Middle Eastern order? Good luck with that. The same logic is currently driving the big regional powers - Iran, Saudi Arabia and Turkey - fueling the sectarian carnage that shows no sign of burning itself out. Clearly, the problems roiling the region are fiendishly complex. Hand-wringing about the original sin of the First World War may carry a seed of truth, but going too far down that path is reductionist.

Nevertheless, whatever we think is the origin of state failure in the Middle East, it is a reality. As the Palestinian Egyptian poet Tamim al-Barghouti writes in a blistering contribution:

new forms of political organization have emerged. Web-like entities, networks whose central node is a cloud of ideas and narratives, float across the region through word of mouth, poetry, music, religious sermons and news bulletins. People exposed to these narratives respond and act, without any central command. The networks thus can form and dissolve as needed. Here, narrative replaces structure, conviction replaces command, and improvisation from the margins replaces central planning. This has been a fundamental characteristic of the recent uprisings in the Middle East.

The darkest instance of this process can be seen in Syria, where “instead of becoming the prize over which factions fight, the state … [has become] itself just one faction among many.” For better or worse, an old order is dying and a new one is yet to be born. The region is today in a perilous no man’s land, with human consequences that are all too grim.

As British-Israeli historian Avi Shlaim writes in the opening piece, “The post-1918 peace settlement is at the very heart of the current conflicts between the Arabs and Israel, between Arabs and other Arabs, between some Arabs and the West.” Many believed that this “post-Ottoman syndrome” was coming to an end when the first optimistic green shoots of Arab protest broke through in late 2010, but since then the situation has drastically deteriorated. Authoritarian regimes have fought back and swathes of the region have been engulfed by sectarian bloodshed. In the words of Egyptian historian Khaled Fahmy, debate now centers on the question: “How did the Arab Spring morph into an Arab nightmare?”

As British-Israeli historian Avi Shlaim writes in the opening piece, “The post-1918 peace settlement is at the very heart of the current conflicts between the Arabs and Israel, between Arabs and other Arabs, between some Arabs and the West.” Many believed that this “post-Ottoman syndrome” was coming to an end when the first optimistic green shoots of Arab protest broke through in late 2010, but since then the situation has drastically deteriorated. Authoritarian regimes have fought back and swathes of the region have been engulfed by sectarian bloodshed. In the words of Egyptian historian Khaled Fahmy, debate now centers on the question: “How did the Arab Spring morph into an Arab nightmare?”