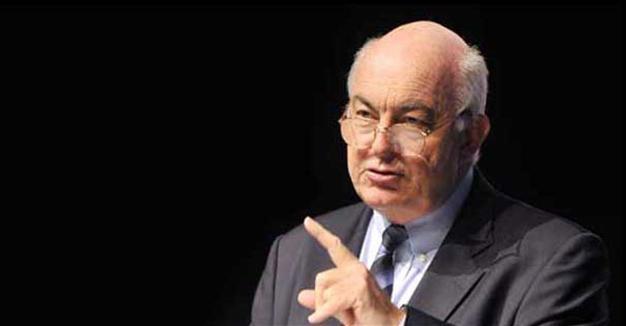

Kemal Derviş is currently at the Brookings Institute. He previously headed the UN Development Programme and served as Turkey’s economy minister in 2001-02, overseeing tough reforms after the meltdown in the country’s banking system in 2000-01.

‘Reflections on Progress: Essays on the Global Political Economy’ by Kemal Derviş (Brookings Institution Press, 208 pages, $21)

The clue of this book by former U.N. Development Programme head Kemal Derviş is in the name. A collection of essays written from 2011 to 2015 for the Project Syndicate website, the title “Reflections on Progress” reflects Derviş’s determined optimism. His almost poignant whiggishness is out of step with the more gloomy spirit of the age. Derviş is the white knight who rode in to save Turkey’s financial system after the huge 2000-01 financial crisis. His reforms imposed stringent regulations of the financial sector to combat chronic, reckless pork barrel spending, while also legalizing Central Bank independence. The changes were painful and led to the liquidation of half of all Turkish banks, but ultimately they yielded impressive results. Derviş’s reforms were one of the reasons why Turkey was relatively resistant to the 2008 global financial crisis.

Derviş is the white knight who rode in to save Turkey’s financial system after the huge 2000-01 financial crisis. His reforms imposed stringent regulations of the financial sector to combat chronic, reckless pork barrel spending, while also legalizing Central Bank independence. The changes were painful and led to the liquidation of half of all Turkish banks, but ultimately they yielded impressive results. Derviş’s reforms were one of the reasons why Turkey was relatively resistant to the 2008 global financial crisis.

Derviş is perhaps the last remaining Turkish public figure you can imagine being comfortable at Davos. A technocrat par excellence, it is surprising that there are not more conspiracy theories about him back in his home country. His focus in “Reflections on Progress” is not on Turkey, where his optimism might today be tested to breaking point. Rather, the book addresses loftier issues of international political challenges, economic transformation and global governance. It’s all very sensible and authoritative, reflecting the experience of a thinker and policymaker with national, regional, and international experience.

The book is organized into three sections: Global economic interdependence, inequality and the political economy of reform, and the specific challenge of Europe. Derviş is an optimist, but he is no naive libertarian. “The creative destruction of the so-called second machine age cannot and should not be stopped. But to think that markets alone can marriage its transformative impact is pure folly,” he writes at one point. He recognizes a key role for the state, but sidesteps questions of whether government should be bigger or smaller. The issue is not whether there should be more or less government, but rather how to make governance better, smarter.

Throughout the book Derviş refers to this conveniently vague solution of “better governance,” but he never really fleshes it out. “The key to managing the disruptions and assuaging people’s fears is governance,” he writes, in a sentence that could mean anything at all: “If the world is to successfully manage the great disruptions lying ahead, governance in the 21st century must, at the same time, be more multilevel, more local, and more global than it has ever been.” Referring to Austrian writer Stefan Zweig surveying the wreckage of the First World War, Derviş writes that “Zweig saw the world fall apart a century ago not because human knowledge stopped advancing, but because of widespread governance and policy failures.”

The reference to the First World War is meaningful today, when the international order is again under great strain. The uneasy current atmosphere is rather different to earlier decades, when Francis Fukuyama could write plausibly in 1992 about the “End of History.” As Derviş remarks wistfully toward the end of the book: “The generation that came of age in the 1960s, which includes myself … believed that, though progress may not be linear, we could count on it. We expected an increasingly peaceful and tolerant world, in which technological advances, together with well-governed markets, would generate ever expanding prosperity.”

Doom-laden news headlines tell a different story - and it’s certainly not fashionable to be a whig in the current age - but Derviş is not entirely wrong. Recent decades have seen steady human advancement in health, global equality, literacy, life-expectancy, and overall wellbeing. Perhaps it is worth looking back to the early 20th century for guidance: Two world wars caused millions of violent deaths and immeasurable suffering, but the long-term gains of progress could not be displaced. Over the longer run medicine improved, technology advanced, gender equality became more widespread. Life for the average person immediately after the wars in 1918 or 1945 was grimmer than it was in 1914 or 1939, but in 1950 it was considerably better than it was in 1900.

Positivity about general human improvement does not necessarily mean faith in the ability of international institutions. According to Derviş, the key is to avoid the destructive international breakdowns such as those that occurred in 1914 and 1939. That is what he is referring to when he talks about “good governance.” In today’s Turkey, where governance is increasingly arbitrary, you notice its absence.