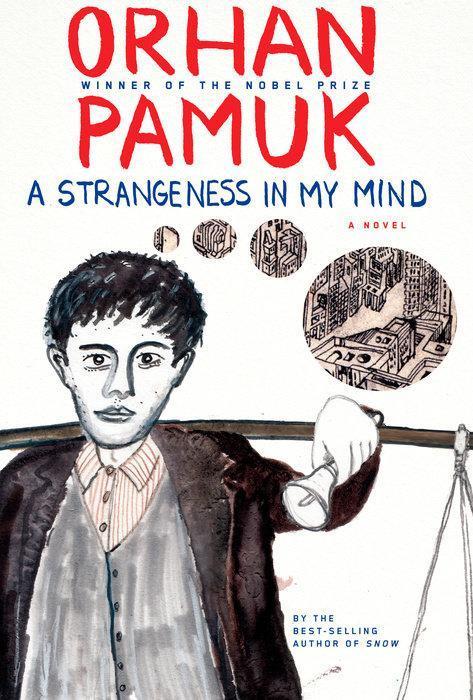

‘A Strangeness in My Mind’ by Orhan Pamuk

William Armstrong - william.armstrong@hdn.com.tr

‘A Strangeness in My Mind’ by Orhan Pamuk, translated by Ekin Oklap (Faber £20/Knopf $28, 624 pages)

‘A Strangeness in My Mind’ by Orhan Pamuk, translated by Ekin Oklap (Faber £20/Knopf $28, 624 pages)Orhan Pamuk’s latest novel is a sprawling 600-page, 40-year saga based on the life of a poor street vendor in Istanbul. At its best, “A Strangeness in My Mind” almost does for modern Istanbul what Dickens did for Victorian London - combining a richly rewarding private story with social insight. It may not be Pamuk’s most sophisticated work, but it is certainly among his most enjoyable.

In many of his novels, the Nobel laureate has focused on Istanbul’s middle and upper classes, sometimes referred to (non-racially) as “White Turks.” In this book, his focus is firmly on the less well-to-do “Black Turks”: A sprawling cast of migrants from Anatolia who built their ramshackle homes on Istanbul’s periphery, who remain attached to their rural traditions, who work temporary menial jobs found through family contacts, and who club together in hometown support associations. This milieu may not be Pamuk’s home territory, but on the whole he pulls of the transition convincingly.

The book’s central character is Mevlut, who spends his winter evenings selling boza, a traditional fermented wheat drink served with cinnamon or roasted chickpeas, favored in the Ottoman era so Muslims could drink low quantities of alcohol in disguise. Street peddlers, with their distinctive calls to woo customers, are a charming but dwindling breed in Istanbul. Boza itself is now an almost-extinct novelty, barely known by younger generations and barely remembered as a nostalgic curiosity by older ones. Mevlut is described as “a living relic of the past that had now fallen out of fashion.”

Over the course of decades, against the backdrop of a turbulent urban landscape, we witness Mevlut writing three years of love letters to the younger sister of the girl he later mistakenly elopes with, work a series of unstable day jobs, father two daughters, and lose touch with previously close friends. Through the many changes in his life, he continues to traipse the distant neighborhoods of Istanbul, selling boza to satisfy what he describes as “a strangeness in my mind.” At times he “feels like himself only when he was out at night selling boza.” Walking fuels his imagination and reminds him “that there was another realm within our world, hidden away behind the walls of a mosque, in a collapsing wooden mansion, or inside a cemetery.”

Alongside the third-person narrative, the book is full of sections narrated by its various characters, giving it a polyphonic feel reminiscent of Faulkner. Pamuk has used this technique in his previous work, but “A Strangeness in My Mind” has a charming simplicity that he has rarely achieved before. His last novel to appear in English “The Museum of Innocence” was around the same length and similarly rambling, but it severely tested the reader’s patience. In comparison, this is an involving and gratifying read full of humor and psychological perceptiveness. It is rather centerless and meandering but it is never boring. The translation by Ekin Oklap is as lucid as the work of Pamuk’s celebrated previous collaborator Maureen Freely.

But the book still suffers from a problem that has dogged the author throughout his career. Just like the central characters in most of his novels, Mevlut is basically Pamuk himself. This is fine when the protagonist is believable as a sensitive literary soul, but it jars when he is a humble Istanbul boza seller. That is a shame because “A Strangeness in My Mind” otherwise manages to skillfully depict the quotidian texture of humdrum daily life. This is particularly impressive for an author with such a high profile in Turkey, who for years has had to be accompanied by a bodyguard in public.

Major social events occur - the left-right street violence of the 1970s, the 1980 military coup, the earthquake of 1999 - but they tend to remain in the background. We witness Istanbul metamorphosing at such a rapid pace that memories begin to “seem like fairy tales.” Its population is a modest three million when Mevlut first arrives, but over three decades it swells to become the out-of-control megalopolis it is today. Toward the end, our hero reflects that the city’s streets have “become part of his soul,” but they are changing fast: “There were too many words and letters, too many people, too much noise. Mevlut could sense a growing interest in the past, but he didn’t expect this would do much for boza … The older generation of street vendors had been swallowed up in the tumult of the city.”

Informed readers understand the subtext of Turkey’s neoliberal reshaping when Mevlut works for six weeks as a parking attendant at an advertising agency high-rise in the early 1990s; or the social change implied when he becomes a cautious acquaintance of a group of suburban political Islamists in the 1980s. The subtlety with which he draws these vignettes elevates Pamuk to a class above any other contemporary Turkish novelist. His mature style may be less ambitious than the daring innovation of his earlier work, but it has far more emotional heft.

‘A Strangeness in My Mind’ by Orhan Pamuk, translated by Ekin Oklap (Faber £20/Knopf $28, 624 pages)

‘A Strangeness in My Mind’ by Orhan Pamuk, translated by Ekin Oklap (Faber £20/Knopf $28, 624 pages) In many of his novels, the Nobel laureate has focused on Istanbul’s middle and upper classes, sometimes referred to (non-racially) as “White Turks.” In this book, his focus is firmly on the less well-to-do “Black Turks”: A sprawling cast of migrants from Anatolia who built their ramshackle homes on Istanbul’s periphery, who remain attached to their rural traditions, who work temporary menial jobs found through family contacts, and who club together in hometown support associations. This milieu may not be Pamuk’s home territory, but on the whole he pulls of the transition convincingly.

In many of his novels, the Nobel laureate has focused on Istanbul’s middle and upper classes, sometimes referred to (non-racially) as “White Turks.” In this book, his focus is firmly on the less well-to-do “Black Turks”: A sprawling cast of migrants from Anatolia who built their ramshackle homes on Istanbul’s periphery, who remain attached to their rural traditions, who work temporary menial jobs found through family contacts, and who club together in hometown support associations. This milieu may not be Pamuk’s home territory, but on the whole he pulls of the transition convincingly.