15 graphs to explain why populism could wreck Turkey’s economy

The political race for the June 7 general elections in Turkey is turning into an auction of populism, which looks increasingly dangerous for the already-strained economy.

This month, Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoğlu, the leader of Turkey’s ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP),

announced that the public sector would hire 120,000 people to plant trees and

raise the retirement pension by 100 Turkish Liras, weeks after he heralded a 50 percent increase in the

on-duty bonuses paid to health personnel.

Meanwhile,

Turkey’s Prime Ministry has spent 460.7 million liras of its total yearly budget of around 1 billion liras in the first two months of the year. Separately, the government spent 539.1 million liras for social benefits in February 2015 (the expense for February 2014 was only 195.1 million liras.)

Days before Davutoğlu’s latest statement, the main opposition Republican People’s Party (CHP) chairman Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu

promised to give pensioners regular bonuses if the party is elected as Turkey’s new government. On April 12, he upped the ante,

vowing to write off “at least 80 percent” of the debt of 5 million citizens who owe banks millions of liras due to their personal credit card spending.

Pensioners, public servants, debtors and the unemployed consist of a massive voting base that can indeed swing the outcome of the crucial elections, but irrational populism can simply break the Turkish economy, which is extremely fragile now.

The following graphs that I compiled from our economy experts

Uğur Gürses,

Erdal Sağlam,

Emre Deliveli and

Mustafa Sönmez show why Turkey needs fiscal discipline and balance of payments more than ever, instead of populist electioneering:

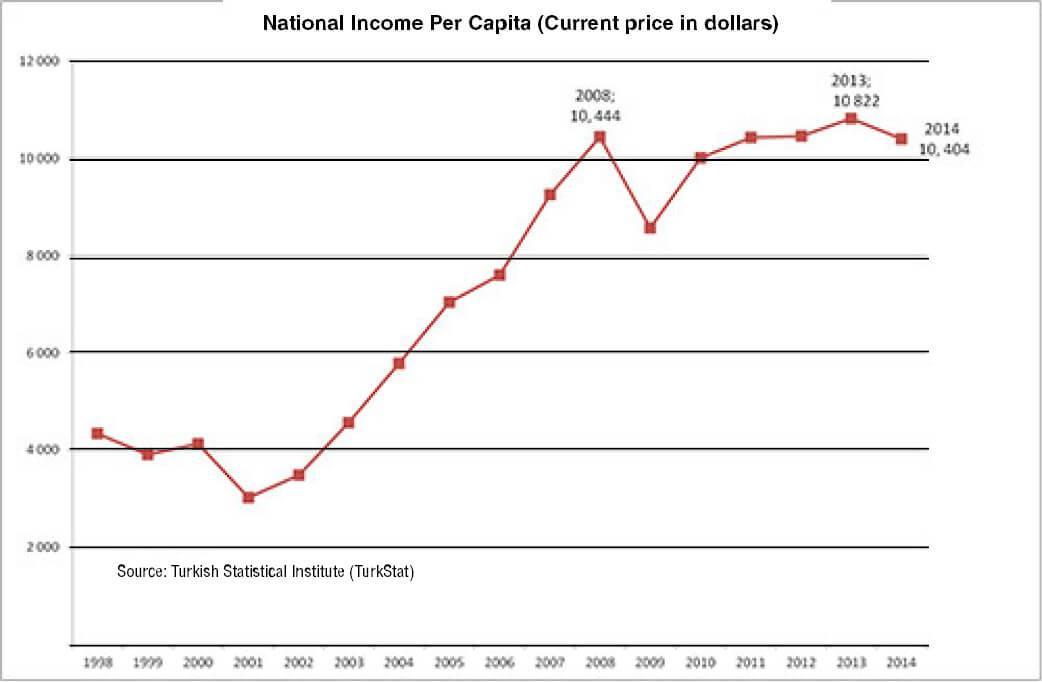

1) INCOMETurkey’s per capita income climbed between 2002 and 2008, but it has stuck around $10,000 level since then, leading some experts to conclude that the country fell into the notorious

middle income trap.

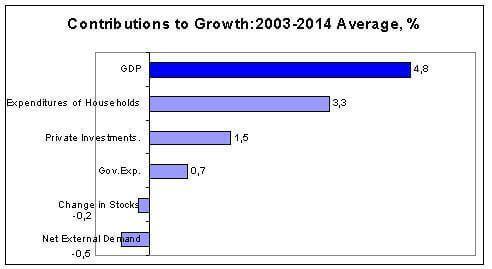

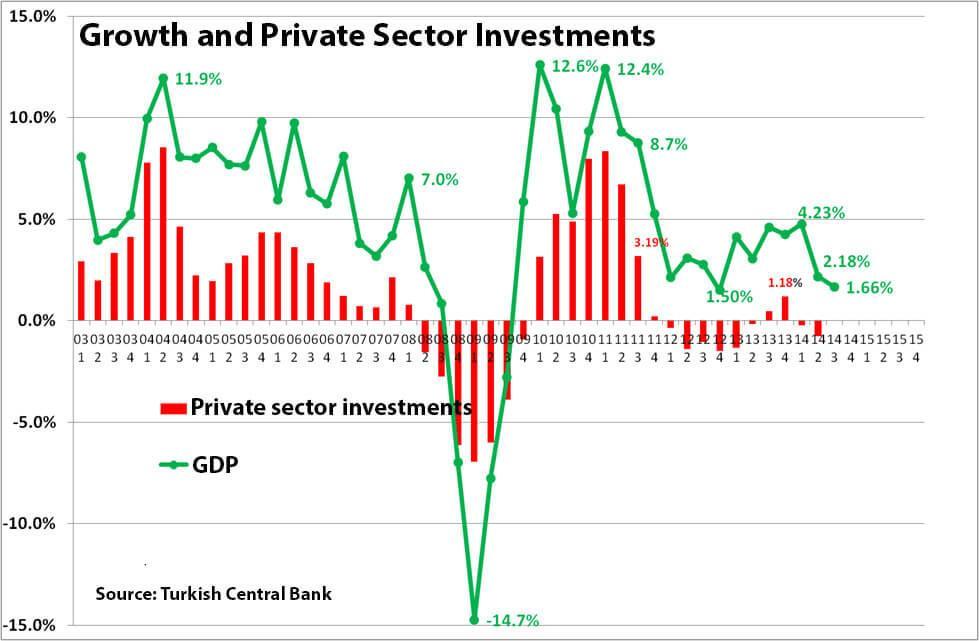

2) GROWTHAt 2.6 percent annually, growth for the fourth quarter of 2014 came in significantly higher than its expectations of 2.1 percent. But it was almost entirely from inventory-build up and private consumption,

Deliveli points out, as a matter of concern.

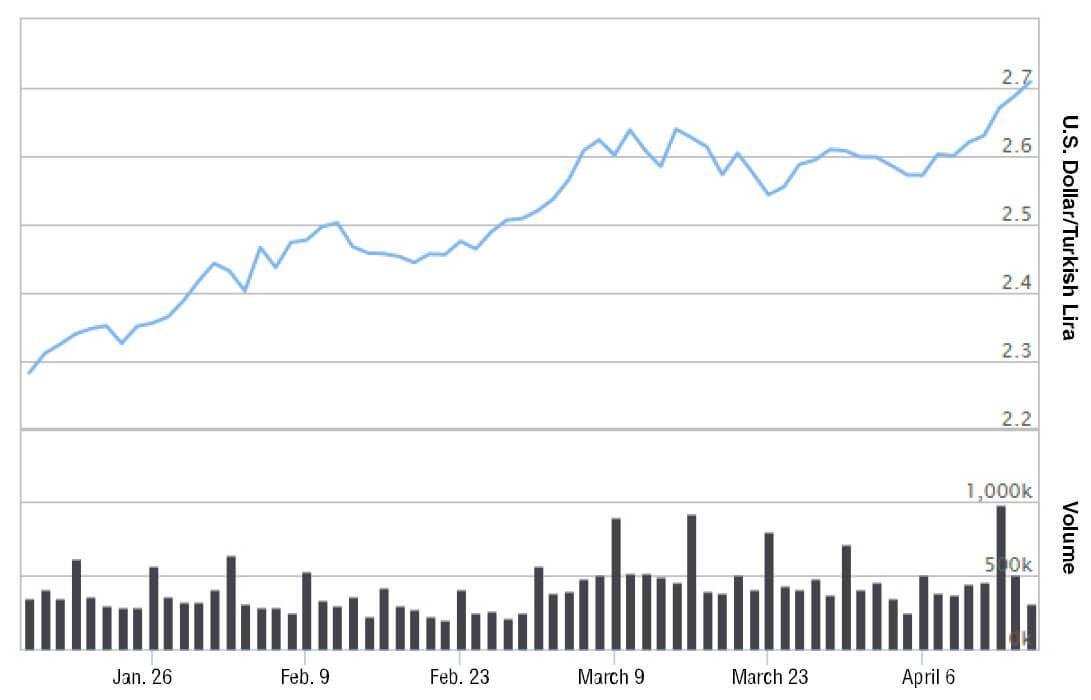

4) WEAKENING LIRA

Turkey, like many other developing countries, has been taking advantage of the weak dollar for years. It was also one of the developing countries hit worst when the dollar recently strengthened. On April 15, the lira hit a new low against the dollar at 2.71 and the Central Bank’s foreign currency reserves quickly lost $10 billion. In addition,

Gürses says that a total of $3.1 billion left Turkey from January 16 to March 20.

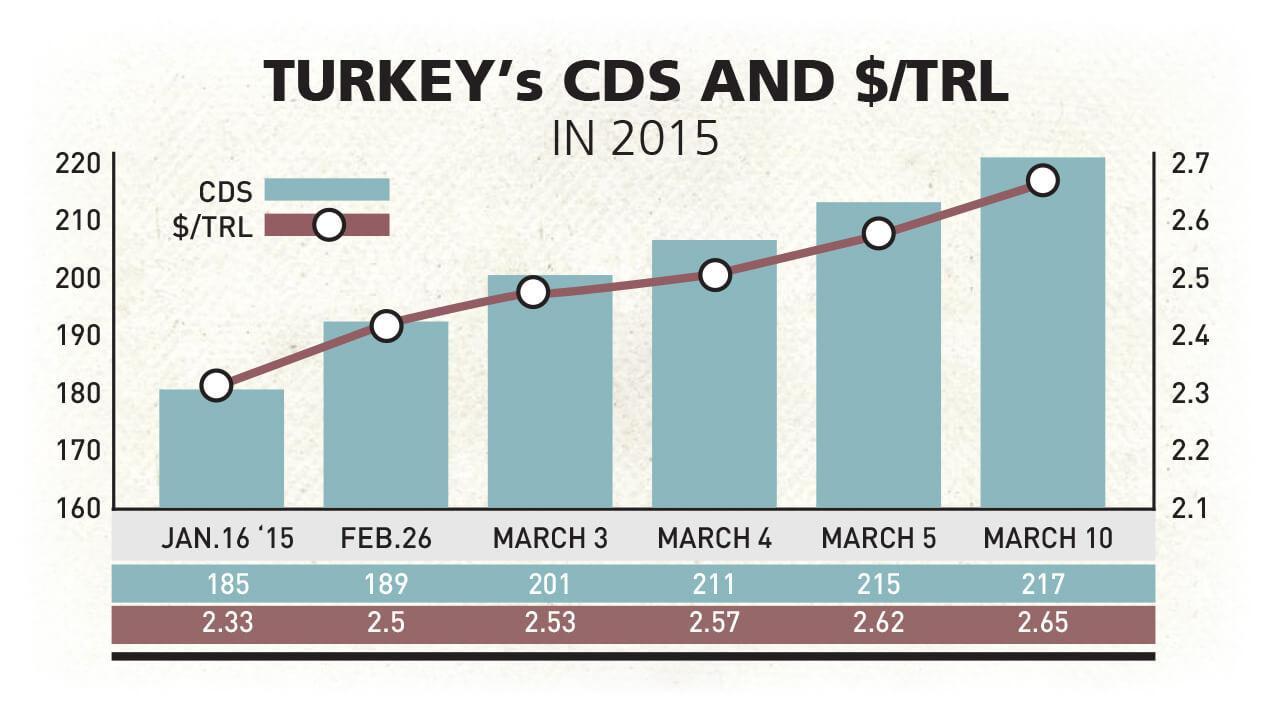

5) CENTRAL BANK INDEPENDENCESeveral analysts said President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s rebukes against the Central Bank played a role in the process in which Turkey’s credit default swap (CDS) also climbed rapidly after his angry outbursts.

6) DEBTS AND CAPITAL INFLOWS

Meanwhile, household debt as a share of disposable income is rising alongside foreign debt per capita, but capital inflows from an unknown origin, thought it cannot be explained, keep saving the day for Turkey, as

our economy editor, Güneş Kömürcüler, pointed out. For how long will this mysterious money keep pouring into Turkey?

7) UNEMPLOYMENT

According to the official data announced on April 15,

Turkey’s unemployment rate climbed to its highest level since 2010. For most voters, it is currently Turkey’s top problem and everyone had seen it coming. As economist

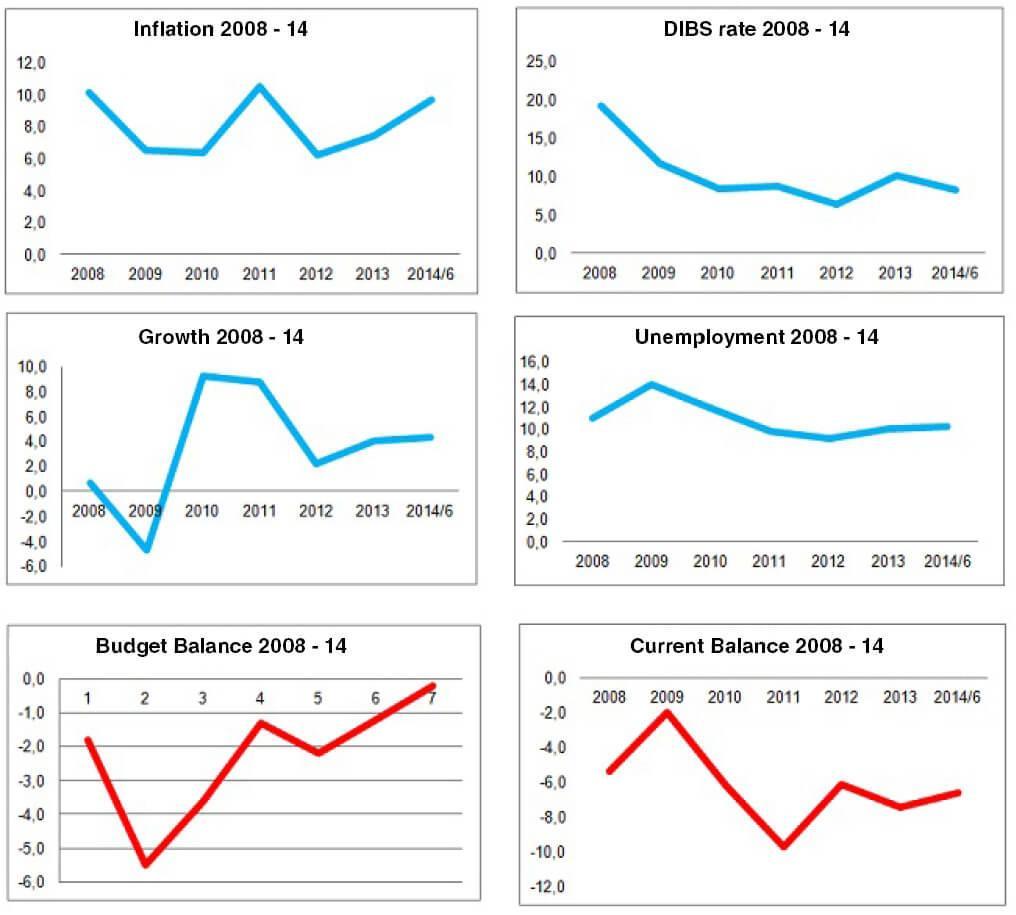

Mahfi Eğilmez shows, unemployment, as well as inflation and the current account deficit, has been rising in recent years, although important progress has been made for a more balanced budget and lower interest rates in the past six years.

8) ILLUSION OF SUCCESS

In fact, the Turkish economy presents one of the bleakest pictures in the world, considering its current account balance and gross savings data. Turkey’s economic rise in the early 2000s was not a miracle at all, as it did not significantly outperform other countries. Its GDP growth was around the global average and way behind most of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries.

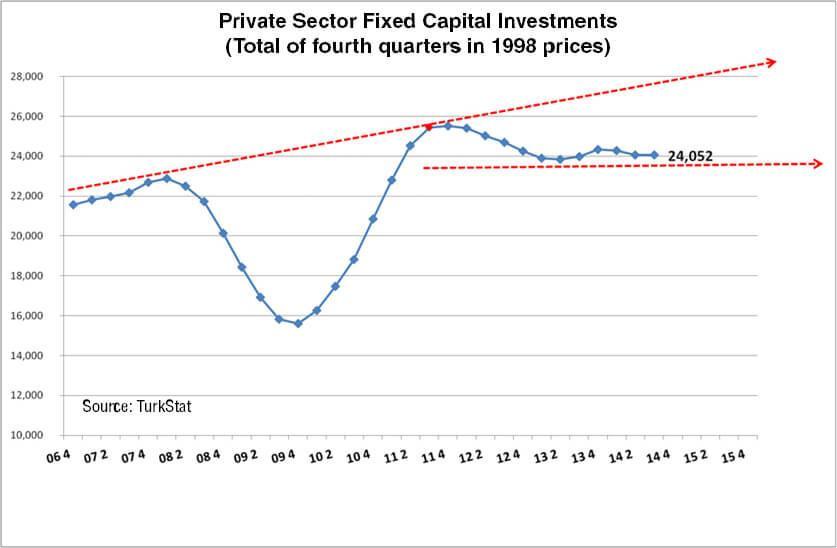

9) INVESTMENTSPrivate sector’s fixed investments, which have a correlation with Turkey’s growth, have been stalling since 2011.

According to Gürses, Turkey has recently not been able to attract investments despite lower interest rates and several public incentives, because it could not provide investors an assuring political and legal climate.

10) FUTURE “The Turkish economy is not doing well at all, as confirmed by the latest data,”

Deliveli concludes, pointing to the plunge of consumer and real sector confidence last month. “Growth difficulties will continue this year,”

Sağlam predicts, stressing that the upcoming elections may further strain economic balances.

In short, it’s time for Turkish politicians to come to their senses and not exchange the country’s future with today’s votes.

The political race for the June 7 general elections in Turkey is turning into an auction of populism, which looks increasingly dangerous for the already-strained economy.

The political race for the June 7 general elections in Turkey is turning into an auction of populism, which looks increasingly dangerous for the already-strained economy.