Doing Business or don’t do business

My favorite Turkish construct is the “me/ma” suffix, which could mean “ing” or “don’t.” So “iş yapma” would be the Turkish for the World Bank’s (WB) annual “Doing Business” report. It could also translate as “don’t do business.”

The latter would be more appropriate if

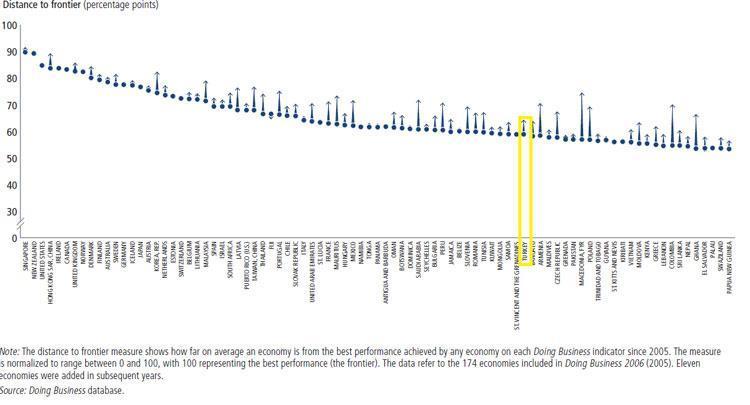

the latest version of the report, which was released on Oct. 23, is any guide. Turkey was ranked 71th out of 185 countries, down three places from last year. The rankings are based on 10 indicators relating to “regulations that apply to an economy’s businesses during their lifecycle, including start up and operations, trading across borders, paying taxes, and protecting investors.”

These indicators don’t cover everything that matters to firms and investors. For example, they don’t include macroeconomic stability and financial resilience, to which markets pay more attention. Credit-rating agencies and

my blog’s host Roubini Global Economics are

more cautious on Turkey precisely because they take into account microeconomic and structural factors as well.

I would not be too worried about Turkey’s rank if it had implemented several reforms and had fallen behind simply because other countries had made even more changes. But the country improved only in two out of the 10 areas during the past year. According to the bank, Turkey eased the enforcement of contracts by introducing a new civil procedure law and made dealing with construction permits easier.

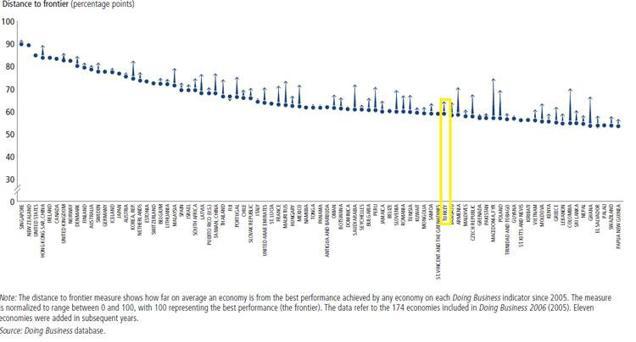

Last year’s mediocre performance is by no means an exception. The bank also calculates the distance of each economy to the frontier, which is “the best performance of each of the Doing Business indicators across all economies and years since 2005.” Turkey has made modest progress by this gauge despite major improvement in certain areas such as starting a business.

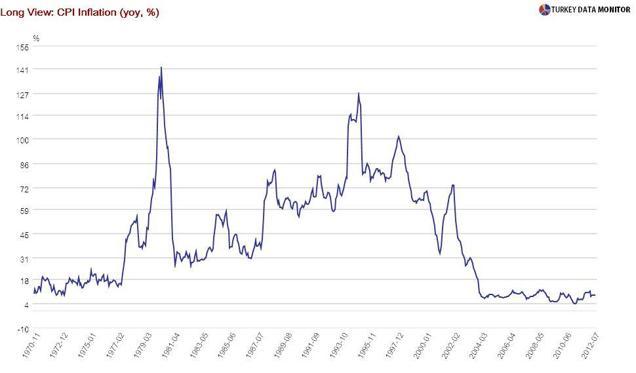

The first Justice and Development Party (AKP) government from 2002 to 2007 could be excused, as they were busy fixing the economy. And they did a fine job at that by sticking to the program prepared by former Economy Minister Kemal Derviş and the International Monetary Fund (IMF): Turkey saw single-digit inflation for the first time in many years, and the banking system was strengthened.

The 2007 general elections offered the AKP a golden opportunity for reform: a very strong mandate and a healthy economy. I have yet to figure out why

they did not proceed with reforms. Likewise, while many countries used the 2008 global crisis as an opportunity to implement politically difficult measures, the government sat out, as economy tsar Ali Babacan candidly noted during the 2009 IMF-WB meetings in Istanbul.

Unfortunately, not much has happened since then, either. It is not that the government does not know what needs to be done. You see the necessary measures listed in government documents, but then nothing happens.

So you can forgive me for not being too excited when I saw several actions geared toward doing business in the government’s

Medium-Term Program, which was published on Oct. 9.

My favorite Turkish construct is the “me/ma” suffix, which could mean “ing” or “don’t.” So “iş yapma” would be the Turkish for the World Bank’s (WB) annual “Doing Business” report. It could also translate as “don’t do business.”

My favorite Turkish construct is the “me/ma” suffix, which could mean “ing” or “don’t.” So “iş yapma” would be the Turkish for the World Bank’s (WB) annual “Doing Business” report. It could also translate as “don’t do business.”