Bosphorus through the decades on screen

Emrah Güler

On Aug. 26, the hills of the Bosphorus, two continents greeting one another, welcomed a third bridge over the waters running from the Black Sea to the Marmara Sea; a third intruder for many civil society organizations, environmentalist groups and concerned citizens, on grounds that it will destroy the remaining green area and the water supply in Istanbul.

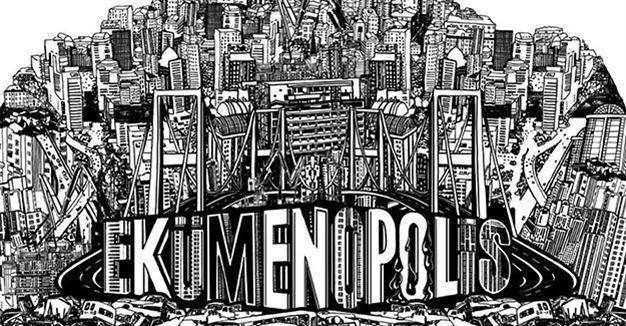

Not fazed, perhaps even fuelled, by the protests in the last decade for the third bridge over Bosphorus, President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan said in the opening ceremony that Turkey would continue to build “mega infrastructure projects.” In her 2011 groundbreaking documentary “Ekümenopolis: Ucu Olmayan Şehir” (Ecumenopolis: City Without Limits), İmre Azem precisely takes a look at that, the mega infrastructure projects, and their impact on Istanbul and its citizens.

The film is a detailed look at the effects of neoliberal policies that began sweeping the world after the 1980s, and more specifically in the last decade and how the Justice and Development Party (AKP), when it became the ruling party, began its quest to transform Istanbul from an industry-based city into a finance and service-centered metropolis. Interviews with academics, experts, writers, contractors, city-dwellers, community leaders, and activists show the harrowing impact of these policies over city-dwellers and shantytowns, as well as the environment.

The documentary takes a look at the uncontrolled growth of skyscrapers in a “megashantytown of 15 million struggling with the mesh of life-threatening problems,” closed residential areas for the upper middle classes and the so-called “urban renewal” projects for the poor, showing how they are widening the gap between the rich and the poor. “Ekümenopolis” questions this mega-transformation, as well as the dynamics behind it.

Perhaps to understand urbanization, and later the uncontrolled urbanization, of Istanbul, one needs to take a look at Turkish cinema, and to see how its love with Istanbul changed over the decades. Istanbul was a major player in almost all of the Yeşilçam melodramas of the 1960s and 1970s, serving as a promise for better lives and better futures.

Three films in three decades

It was a period where Istanbul welcomed new citizens from across rural Turkey, on and off screen. Haydarpaşa Train Station was the ultimate symbol of migration, always the final stop in a long train ride from stilted lives to brighter futures, before the characters sailed off to better lives through the Bosphorus. The green hills of the Bosphorus served as the ideal backdrop for stories of love, heartbreak, hope and disappointment.

As more people flocked to Istanbul, again both on and off screen, shantytowns began taking their places next to the dreamy mansions overlooking the Bosphorus. Academic Mehmet Öztürk cites late director Atf Yılmaz’s “Suçlu” (Criminal) of 1959 as the first film to portray “the new urbanization of Istanbul,” to include scrappy shanty towns.

Last year, Istanbul Modern, Istanbul’s center for contemporary art, screened three Turkish films from three decades, featuring the Bosphorus as a major backdrop in the story. Director Ö. Lütfi Akad’s 1959 film “Yalnızlar Rıhtımı” (The Quay of the Lonely), starring off-screen couple Sadri Alışık and Çolpan İlhan, features a love triangle juxtaposing the underbellies of Istanbul against the beautiful, green hills of the Bosphorus.

The second film in the program was Nejat Saydam’s “Boğaziçi Şarkısı” (The Bosphorus Song) of 1966, starring Selda Alkor and Tamer Yiğit. The first 20 minutes of the film is a Bosphorus tour, accompanied by songs of the period, as a group of female students take an Istanbul tour on screen. An accident on the Bosphorus kick-starts a passionate love affair, with the strait continuing to be an integral part of the setting.

In another love story, 1971’s “Tophaneli Ahmet: Bir Aşk Hikayesi” (Tophaneli Ahmet: A Love Story), director Sırrı Gültekin uses the Bosphorus as the epitome of romance, taking its characters from one corner of the strait to another, historical places like Rumeli Hisarı scattered occasionally on screen. Watch these films, topping them with “Ecumenopolis,” to see the vast change Istanbul, and hence the Bosphorus, has gone through.

On Aug. 26, the hills of the Bosphorus, two continents greeting one another, welcomed a third bridge over the waters running from the Black Sea to the Marmara Sea; a third intruder for many civil society organizations, environmentalist groups and concerned citizens, on grounds that it will destroy the remaining green area and the water supply in Istanbul.

On Aug. 26, the hills of the Bosphorus, two continents greeting one another, welcomed a third bridge over the waters running from the Black Sea to the Marmara Sea; a third intruder for many civil society organizations, environmentalist groups and concerned citizens, on grounds that it will destroy the remaining green area and the water supply in Istanbul.