‘We ate the horses, you rode them afar’

BELGİN AKALTAN - belgin.akaltan@hdn.com.tr

The “you” above are us, the Anatolian Turks. The “we” are the ones who stayed behind at Central Asia. We came all the way from Central Asia riding on horseback, while the other part of our ancestors stayed where they were. This Turkic migration went on for centuries.

This sentence above is what is being said to visiting Turks in Central Asia, I have been told.

It is like the philosophical essence of the history of Turks. Let me put the Turkish version here to complete the spirit: “Siz atlara binip gittiniz, biz atları kesip yedik.” I shudder at the layers of meaning in this sentence every time I hear it; the connection with our ancestors, the wisdom, the realistic approach, the analytical captivation, the kindness shown to a guest, the humbleness and the subtleness of the offered compliment.

This piece is in memory of my friend Servet Somuncuoğlu on the second anniversary of his death. He died of a heart attack at home on a sad August day in 2013 at age 49. He was an exceptional human being and he left this world with many hearts bleeding for him. As you are reading this piece, a memorial ceremony is being held at Altunizade Cultural Center, on Istanbul’s Asian side.

He was first our neighbor, then our friend, then our dearest friend. We lived in the same apartment building for about 20 years; our sons grew up together and became best friends. In my smoking days, I would knock at his door at 2 a.m. if his light was on to ask for cigarettes; he would do the same.

He loved his village in Bursa, Karacabey, but he was actually from the Black Sea, Giresun. He always wanted to take us to his village but it was on the day he died we finally made it to his İsmetpaşa village. I could only stay until midnight because the sadness hanging in the air was too heavy for me; my son drove me back to Bursa. I wish I would tease him about his beloved village, “Is this the village you constantly told us about? It is too hot, there are too many flies and the smell of animal feces is everywhere.” He would make us see the beauties of the places that we, mortals, are not able to see.

Back to the horsey sentence above: The horse-eating ones are our Central Asian ancestors who stayed in their lands, did not bother to explore, travel and look for new lands, but remained in the comfort of eating their horses. This sentence is like the snapshot of Turkish history. It explains the spirit of the Turks riding on horseback, that culture, the brave, daredevil fighting spirit that we all have. The other explains the other side of us; the more comfort-loving, lazy, non-exploring, staying at home feature of ours, the one who wastes our own resources for short-term needs.

I think we modern Turks possess both characteristics. We love comfort; we cannot let go of our comfort, but there are also our victories, accomplishments we have achieved with our explorer side - the “whatever is left” from our Turkic instinct of surviving in difficult times.

Turks were present before Islam, of course. This is the time before we met Islam. This is the time when women were queens ruling society, not treated as second-class people like today. Some people miss the Ottoman times; some people like me miss the pre-Islam times of the Turks…

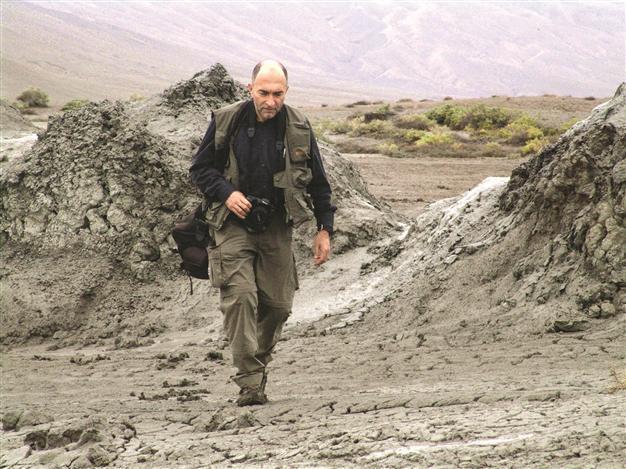

Servet Somuncuoğlu was a researcher of early Turks. He was an extensive traveler; he has been to godforsaken places not only in Central Asia but anywhere else in the world. He was a Turkologist, a researcher, a documentary film producer, a director, photographer, writer and I think a philosopher.

Can somebody continue teaching two years after he has died? He does. This sentence was one I heard after he died. So typical of him; he continues teaching us even from the other side.

The unusual side of our friendship was that we were from different “neighborhoods.” He was a nationalist. In “my neighborhood,” nationalists and being friends with nationalists is not “cool.”

When we told our children that we would not even sit at the same table, let alone become friends, if we had met in the 1970’s when Turkey was separated into left and right - and when leftists and rightists were killing each other - our children stared at us with unbelieving eyes.

(Also, there were no Kurds then. I mean, this is a painful sarcasm, summing up modern Turkish history. Yes, there were no “problematic” Kurds in the 1970’s. They started appearing in the 1980’s. There were no headscarf-wearing women wanting to attend universities either. They were only cleaning houses then. They started appearing in the social arena only in the 1990’s.)

Servet Somuncuoğlu was a true believer in Turks. I was on the other side of the political spectrum. He was a true nationalist. I was a leftist, social democrat; I would have wanted to call myself a communist.

He would tell us history, things we never knew. In his assistant Selda Serin’s words, “He devoted his life to Turkishness; he worked for it, he produced endlessly. Besides his documentaries, books, articles, photographs and research, he also touched the lives of everybody, whoever he communicated with, with a word of his, with an act of his, with his kindness and wisdom. He was a man of heart, leaving his traces on everyone…”

He traveled intensely for his research, from mountains to lakes. He loved nature, he loved his family, he loved people and he loved being a Turk.

I am not a nationalist but I have a nationalist side in me which I believe is present in every Turk. We Turks love our country, our existence, our history, our language. Carrying that any further is optional.

His wife and son are keeping his library, his collections, his computer, his archives and his photographs open to researchers. As I said, his assistant, a wonderful person, Selda Serin, is continuing his studies. She is a lecturer and a Ph.D. candidate at Kyrgyz-Turkish Manas University. I see her photographs from the mountains on Facebook.

People are still remembering and commemorating him; people from opposite sides of society. He has a book titled “Gallemit,” on the life and philosophy of Muzaffer Sarısülük, who is the father of Ethem Sarısülük, the Gezi park victim shot by a police bullet in Ankara.

He once wrote about his research and its future: “What I am doing is journalism, television journalism, photo journalism… But what needs to be done after this is that an institute should be formed on this topic.

In this institute, people from diverse disciplines such as archaeology, art history, sociology, anthropology, history, Turkology, ethnology, philology, even psychology, philosophy and photography, should get together and first, an inventory should be made and afterward the work of interpreting this inventory containing the Turkish culture and civilization findings of the antique era should start…”

I wanted to write about him but I ended up writing about our friendship. This is what happens when you lose a friend.

I wish he was alive and I could discuss the state of political nationalism in Turkey these days. He sometimes disliked and harshly criticized his party and its leader. Now should be one of these times. His Turkish nationalism was above and beyond daily political matters.

I think we have started eating our horses nowadays Servet, my dear friend.

https://twitter.com/belginakaltan

http://belgin.akaltan.com

The “you” above are us, the Anatolian Turks. The “we” are the ones who stayed behind at Central Asia. We came all the way from Central Asia riding on horseback, while the other part of our ancestors stayed where they were. This Turkic migration went on for centuries.

The “you” above are us, the Anatolian Turks. The “we” are the ones who stayed behind at Central Asia. We came all the way from Central Asia riding on horseback, while the other part of our ancestors stayed where they were. This Turkic migration went on for centuries.