The renaissance of an Ottoman Armenian feminist

William Armstrong - william.armstrong@hdn.com.tr

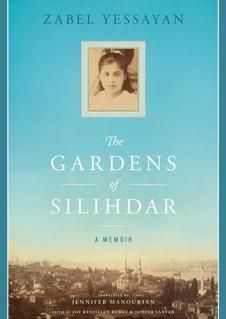

‘The Gardens of Silihdar’ by Zabel Yessayan (AIWA Press, 163 pages, $20)

‘The Gardens of Silihdar’ by Zabel Yessayan (AIWA Press, 163 pages, $20)

The late 19th century witnessed an extraordinary flourishing of Ottoman Armenian culture that has since been described as an “Armenian renaissance.” The rapid growth of schools, social organizations, periodicals and European trends led to a transformation in the language and intellectual landscape of the Ottoman Armenian community - similar to elsewhere in the empire.

Along with this cultural ferment was a new emphasis on the advancement of women in Armenian society, and a number of women intellectuals reached positions of prominence previously unheard of in a rigidly hierarchical community. Although her name was almost forgotten in the decades after her death in the 1940s, Zabel Yessayan is currently experiencing something of a mini-renaissance of her own thanks to a couple of new translations of her work by Jennifer Manoukian, commissioned by the Armenian International Women’s Association. Yessayan’s pioneering proto-feminism and her descriptions of the social details of a fascinating period make “The Gardens of Silihdar,” her memoir of growing up in late 19th century Ottoman Istanbul, a fascinating artefact.

Born in the Silihdar neighborhood of Üsküdar, on the Asian side of Istanbul, Yessayan provides a vivid portrait of an introverted, deeply conservative Armenian community and its characters. What starts as a fairly unremarkable memoir develops into a more sophisticated portrait of the artist as a young woman, describing her coming of age from a restless and tempestuous child to a melancholy, talented young woman. French and American schools were proliferating at the time, and new fashions and ideas were shaking traditional life in metropolitan areas across the Ottoman Empire. Yessayan’s father was himself influenced, keen not to create obstacles for his daughter, open-minded and encouraging Zabel to develop her interests and get a sound education. Her portrait of him is as sympathetic as anyone in the book (there aren’t many sympathetic portraits), although his spendthriftiness meant that the household was wracked by financial instability. “The days my father needed to repay his debts did not just arrive; they exploded like bombs,” Yessayan writes.

As for communal relations, she draws a familiar picture of a guarded tolerance being gradually, inexorably overtaken by political tension. At one point her family temporarily moves to a Turkish village a few miles away for her mother’s health, and she reflects: “A few years later, it would have been impossible for an Armenian family to live safely in an entirely Turkish village, but in those days there were still no traces of ethnic tension between Armenians and Turks, and the two peoples treated each other with a calm sense of shared humanity.”

Yessayan was born in 1878, and came of age at a troubled time. A cultural renaissance may have been going on, but it was also an era of accelerating social turmoil, and there are plenty of references in this book to the plight of suffering Armenians in Anatolia. Her growing up was simultaneously a process of awakening and disillusionment. Reflecting on her time at one of the Armenian high schools, she gloomily describes it as “just a miniature version of the adult world that I would come to know, complete with its dirty dealings, narcissism, hypocrisy, lies and selfishness.” It was, she writes, “as if there were a courtroom in my mind where the people I encountered and the things I experienced were subject to harsh, endless judgment.”

Yessayan’s developing feminism was sharpened by the stultifying conservatism of the community. “Those young women could not leave the house by themselves,” she writes angrily, “some were even forced to marry men they despised. They were not free to dress as they pleased or behave as they saw fit. Essentially, they were deprived of their most basic freedoms and feared that, sooner or later, they would be constrained by motherhood - a fate they wished to escape in order to create the lives they had envisioned for themselves.” Dismissive of these tendencies, she had no time as a writer for the “sentimental romanticism” that was the literary fashion of the day, and her own memoir formally remains quite straightforward and undemonstrative.

Years after the events described in “The Gardens of Silihdar,” Yessayan was included as the only woman on the list of Istanbul Armenian intellectuals targeted for arrest and deportation by the Young Turk regime on April 24, 1915. She managed to flee the empire and almost two decades later ended up in Soviet Armenia, where this book was published in 1935. Despite Yessayan’s prominence in late Ottoman Istanbul, her work was essentially ignored after her death in a Siberian labor camp, as a victim of Stalin’s Great Purge. Hopefully it is now beginning to attract the attention that it deserves once again.

‘The Gardens of Silihdar’ by Zabel Yessayan (AIWA Press, 163 pages, $20)

‘The Gardens of Silihdar’ by Zabel Yessayan (AIWA Press, 163 pages, $20) Born in the Silihdar neighborhood of Üsküdar, on the Asian side of Istanbul, Yessayan provides a vivid portrait of an introverted, deeply conservative Armenian community and its characters. What starts as a fairly unremarkable memoir develops into a more sophisticated portrait of the artist as a young woman, describing her coming of age from a restless and tempestuous child to a melancholy, talented young woman. French and American schools were proliferating at the time, and new fashions and ideas were shaking traditional life in metropolitan areas across the Ottoman Empire. Yessayan’s father was himself influenced, keen not to create obstacles for his daughter, open-minded and encouraging Zabel to develop her interests and get a sound education. Her portrait of him is as sympathetic as anyone in the book (there aren’t many sympathetic portraits), although his spendthriftiness meant that the household was wracked by financial instability. “The days my father needed to repay his debts did not just arrive; they exploded like bombs,” Yessayan writes.

Born in the Silihdar neighborhood of Üsküdar, on the Asian side of Istanbul, Yessayan provides a vivid portrait of an introverted, deeply conservative Armenian community and its characters. What starts as a fairly unremarkable memoir develops into a more sophisticated portrait of the artist as a young woman, describing her coming of age from a restless and tempestuous child to a melancholy, talented young woman. French and American schools were proliferating at the time, and new fashions and ideas were shaking traditional life in metropolitan areas across the Ottoman Empire. Yessayan’s father was himself influenced, keen not to create obstacles for his daughter, open-minded and encouraging Zabel to develop her interests and get a sound education. Her portrait of him is as sympathetic as anyone in the book (there aren’t many sympathetic portraits), although his spendthriftiness meant that the household was wracked by financial instability. “The days my father needed to repay his debts did not just arrive; they exploded like bombs,” Yessayan writes.