At

$6 billion, the January

current account deficit came in higher than market expectations of $5.5

billion, not to mention Economy Minister Zafer Çağlayan’s optimistic $4 billion

projection. According to Sabah, this would make Çağlayan a “karavanacı”

(someone who completely misses the target), as the Turkish daily has called

economists whose forecasts have been off.

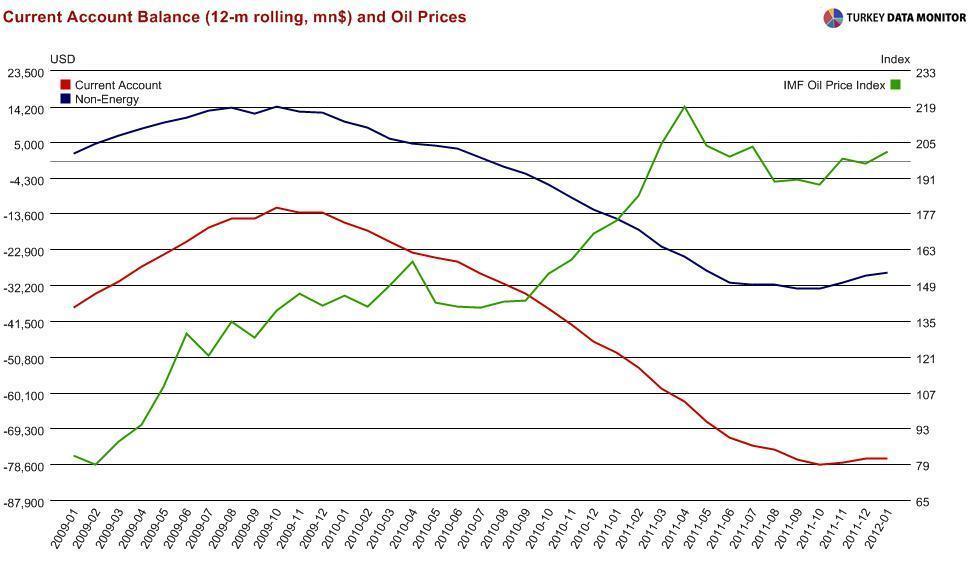

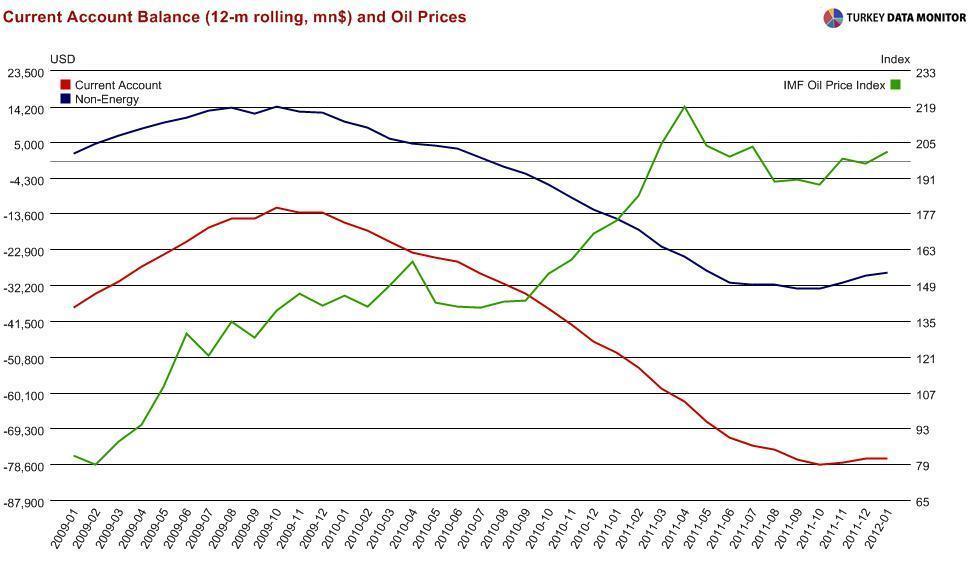

High

oil prices are definitely taking their toll on the current account, but even

the non-energy deficit is not adjusting as quickly as expected. As anyone who

skims Turkish dailies would know, a high deficit is a risk because it makes the

country dependent on foreign financing, basically subjecting it to the whims of

global risk appetite. An economy where the Central Bank governor spends more

time worrying about the Fed and ECB than domestic developments is not

healthy by any means.

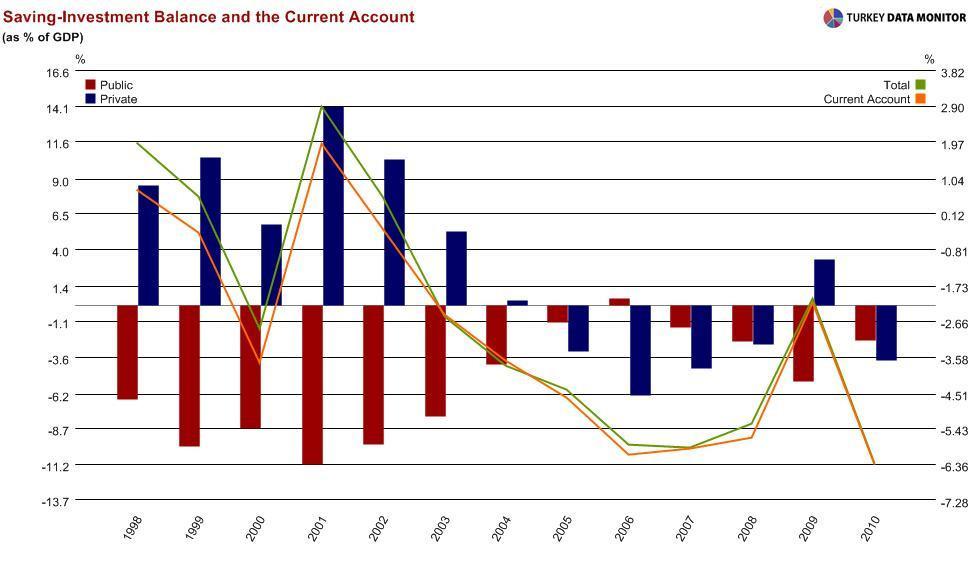

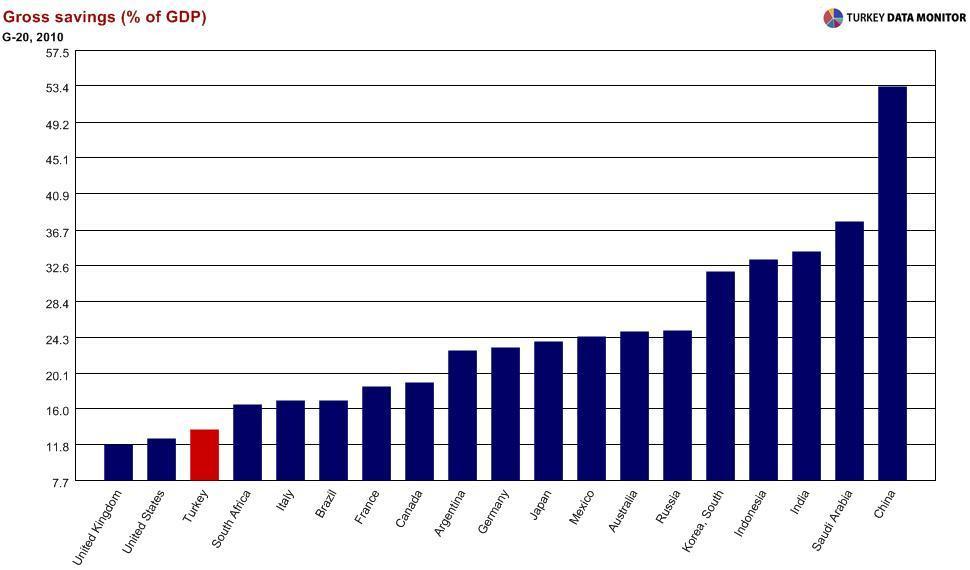

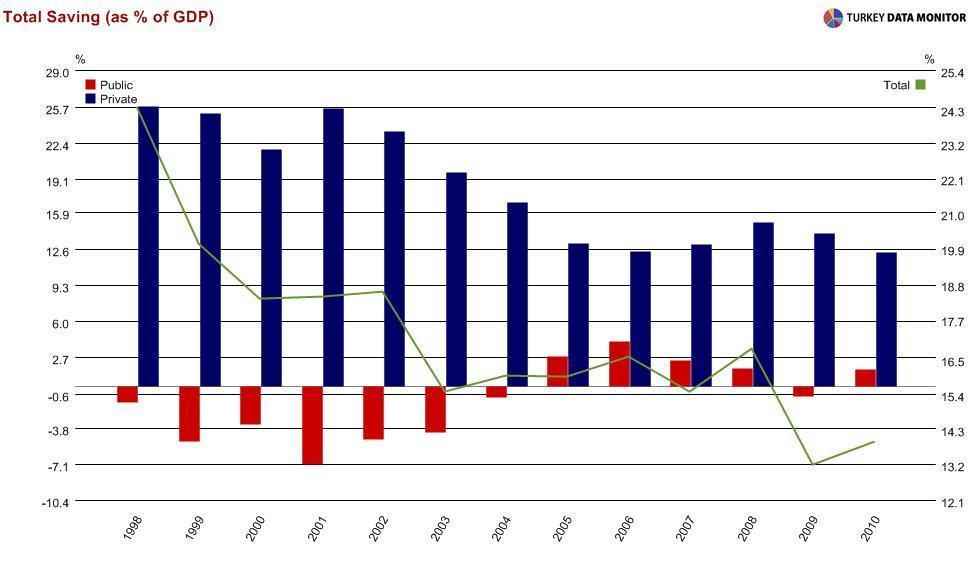

Moreover,

savings have been falling since the end of the last millennium. While public

sector profligacy was behind the decline before the 2001 crisis, the fall in

savings over the last decade has mainly been a private sector phenomenon, as

the government started running a tight fiscal ship as part of the crisis

recovery program.

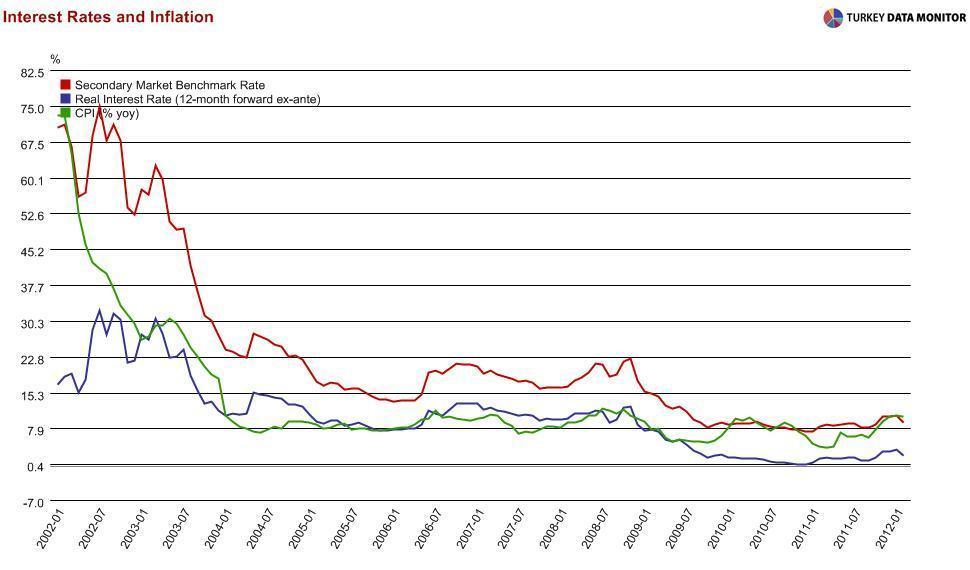

They attribute lower household savings mainly to the “decline in macroeconomic vulnerabilities”: The increased availability of credit, fall in interest rates and postponed consumption more than offset the increase in savings that would be associated with rising incomes. There was also less need for precautionary savings as the economy normalized.

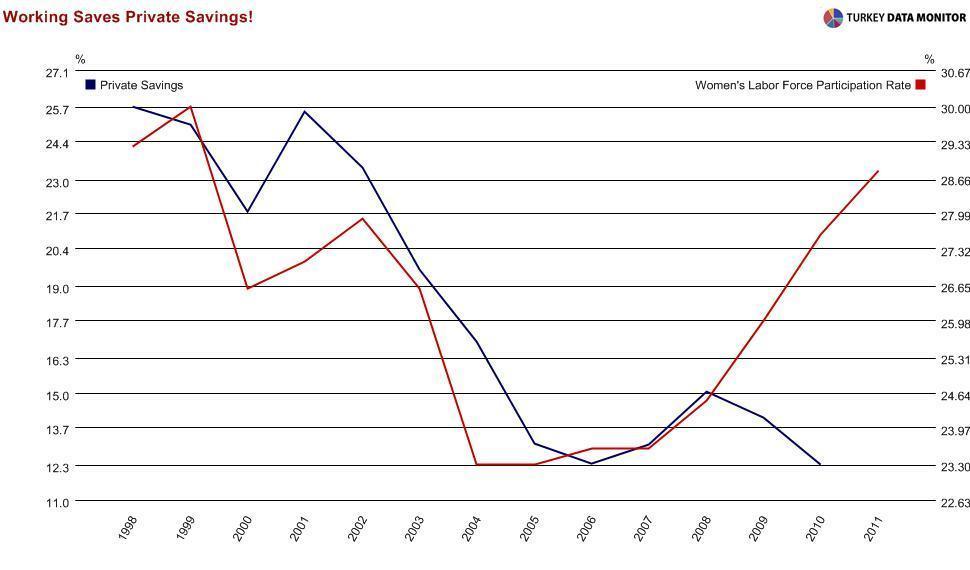

But the real question is how to increase private savings. This is where I will pick up next week, when I will conclude my savings trilogy.