Ich bin ein Berliner!

Aylin Öney TAN - aylin.tan@hdn.com.tr

It was half a century ago: J. F. Kennedy made his speech clear. There he was in 1963, addressing the citizens of Berlin, speaking to them in their own language, telling them that the U.S. was their true ally.

The sole statement “Ich bin ein Berliner/I’m a Berliner” summoned his intention. This might have been one of the first attempts in modern politics to demonstrate such a strong empathy with the general public. He was embraced by the Berliners, this was probably the quickest way to become a citizen ever.

Half a century ago, it was also the start of a great influx of new comers to Berlin. They were guest workers, coming from far away countries; east Europe and beyond, Italians, Greek, Bulgarians and the top of the list Turks. From deep inside rural Anatolia, a great number of Turkish peasants ended up in the wall clad city, remote and isolated in an alien country, far from their homeland in every aspect. They were temporarily welcomed, being stubbed with the nickname “guest,” Gastarbeitern. The forethought was not to embrace them as new citizens, but to send them back to where they came from as soon as possible. The new guests had the same intention. Not welcomed in this alien land, they were reluctant to call themselves Berliners. Given mutual unwillingness to mingle, Germans and Turks remained apart, like water and oil in the glass cage of Berlin, never emulsifying into a smooth cream.

In Anatolia, there is a funny saying about guests: After three days guests stink! Hospitality may be a national sport in Turkey, but even in such a guest-friendly country like Turkey, there is such an inhospitable saying about overstayed guests. But the Turks stayed. Though aware of their shaky existence in Berlin, most Turks never made their way back to their homeland. There were generations to come, new born Berlin citizens, but not Berliners, still being regarded as a second generation of guests. Apparently it was not as instant like Kennedy for the Turks to become true citizens of Berlin, after half a century, their existence in Berlin, though undeniable, is still debatable.

Turks still search for ways to express themselves. Food is one way of expressing oneself and communicating with another culture. Turks still to eat their own food, not really embracing German cuisine. Though Berlin was slow in adapting Turkish cookery, the city has been quick to adopt one single Turkish food: the Döner Kebap. The ubiquitous kebap stalls became a feature of Berlin streets, so much so that, along with Curry Wurst, it was listed in guide books as a typical Berlin street food. In a way, the fast food kebap culture was quick to become a true Berliner.

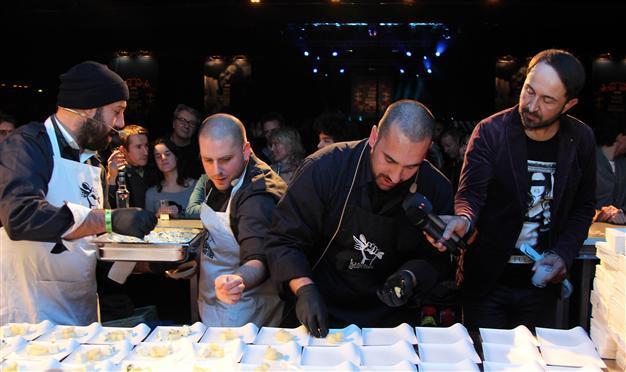

Now the horizon is expanding, with Turkish food showing its nuances to citizens of Berlin. There are more and more trendy or upmarket restaurants popping up here and there, with beautifully decorated interiors, with hip and young customers enjoying Turkish food and Turkish wines, chatting over the local indigenous grapes of Anatolia, debating their preferences of Öküzgüzü or Boğazkere grapes. Young Germans, and their now Berliner-Turkish-origin friends are clicking rakı glasses, the new hip drink on the Berlin scene. Their meeting venues are not the neon lit kebab joints in Kreuzberg, but fashionable chic Turkish restaurants or trendy parties in the Arena, like the “The Spirit of Istanbul Fest” held only two days ago, last Saturday. Discovering Turkish cuisine is also a way for the second or third generation Turks to explore their origins through food. They are becoming proud of being a Berliner, but with a twist, or with a rakı glass. It is a way to establish links between two countries. Promoting Rakı is also a means of promoting tourism in Turkey. This is how Galip Yorgancıoğlu, the CEO of Mey group puts it. The selling numbers are amazing. Rakı ranks 13th in shared sales value in world spirits. A quarter of all anise based spirits is Turkish rakı, with an export of 4.5 million liters. Now Mey group is aiming to make Turkish Rakı a world brand and they launched their campaign from Berlin.

Kennedy was a pioneer in conquering the hearts of Berliners.

Now here is the question. Can Turkish rakı become a true Berliner like beer?

Bite of the week

Cork of the Week: With the wide spectrum of rakı varieties available in the market, there needs to be some information needed for new beginners in Berlin. “Ala”, the most exquisite is made from sun dried grapes, with a high level of anise with the lowest sugar content, and highest alcohol percentage at 47%. “Altın Seri,” the golden series is made from fresh grapes, aged 3 months in oak barrels, hence the golden hue. The good old “Yeni Rakı” is a mix of fresh and dried grapes, being the archetypical rakı, it is a classic.

Fork & Recipe of the Week: An innovative range of new, hip mezzes with a twist from tradition comes from a team of guerillas. This gang of self-appointed, independent chefs operates as a kitchen unit that hijacks restaurants and pops up in events in unusual places. They call themselves “Kitchen Guerillas” and are trailblazers in performing a totally new cult of kitchen. Their motto is “In food we trust” and they try to serve honest, yet unexpected food anywhere any time. Their latest appearance was in “The Spirit of Istanbul Fest” in Berlin. Their smashing mezze of the night was a very simple classic rakı accompaniment with an innovative touch: “Ezine with Melon”. Here comes the secret recipe. The melon is marinated with fennels and anise seeds with a sprinkle of cinnamon with white cheese cubes bathed in Turkish extra virgin olive oil and fresh tarragon. Simply crush the anise, fennel and cardamom seeds in a mortar and toss them over cubed melons, add a touch of cinnamon. Arrange marinated cubes of cheese on top: magical, simple and good with rakı.

It was half a century ago: J. F. Kennedy made his speech clear. There he was in 1963, addressing the citizens of Berlin, speaking to them in their own language, telling them that the U.S. was their true ally.

It was half a century ago: J. F. Kennedy made his speech clear. There he was in 1963, addressing the citizens of Berlin, speaking to them in their own language, telling them that the U.S. was their true ally.