Cartoon icons take on art, humor in Turkey

BODRUM - Hürriyet Daily News

The jury members, led by the wonderful

Adolf Born, included names like Brad Holland and Ralph Steadman. All have previously attended the event, except for Robert Mankoff, the sole newcomer of the group.

To grasp the sum of the brilliance that passed through the shores of Bodrum in the early days of this week, one just had to be there.

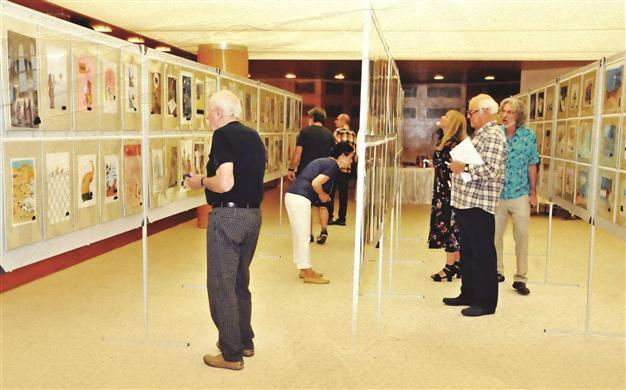

The guest list for this year’s Aydın Doğan Cartoon Contest, which is now in its 30th year, had credentials to blow anyone’s mind: the iconic Adolf Born – who had also been one of the members of the first ever group of judges for the event – Ralph Steadman, Brad Holland, Anita Kunz and in his first time around, Robert Mankoff. It was quite a sight to see when they all gathered together, in addition to their Turkish counterparts that included the likes of Latif Demirci and Ercan Akyol, to judge the entries of the year.

The voting ended in favor of the Polish artist Krzysztof Grzondziel, who emerged as the winner with his cartoon focusing on the traces of war following a day-long session which had the judges slaving over 234 finalists. The cartoon showed an American soldier missing a leg, amid renowned sculpture figures of ancient history.

“It has an interesting quality of pulling everything together and drawing parallels,” Anita Kunz, one of the two female judges on the selection committee, told me later on. “It was interesting in the way it was all pulled together, with the ancient sculptures.”

“This year there seemed to be a lot of things about freedom,” Kunz told me, “In many various forms and in various ways. It’s a worldwide struggle, not only of Turkish people – the ability to live our lives as we want and be respected.”

The great Robert Steadman, as we flicked through his little notebook that included bullet points from the Sao Paulo riots to sketches of women at customs search at the airport, said one of the troubles with the entries nowadays was that they lacked actual drawing.

“Not so many full-blooded, wet drawings anymore,” the master told me, before he added, “In fact, they should ban computer drawings.” As we chatted on, I asked Steadman, who has attended the event six times before, if he noticed any changes in Turkey.

“Always lovely,” Steadman told me at first, and added, “There is still an exotic feel to it when they are not trying to be modern.”

“I think that’s one of the modern problems. It shocks me about Erdoğan that he wants to build a mall when there are all these beautiful bazaars in Istanbul. And he wants to take away the lovely trees? That is ugly commercialism. It is really wrong headed, and the financiers seem to be controlling things, and certainly controlling common sense. It saddens me,” he said.

The impact of humor Steadman said the works of art may look “like marks on the wall” (“Especially if it’s a print-out”) but carried a great value.

“If somebody stops you in your tracks, could be an eyeball or a hand, and is making a point, then, that’s important. It stops you, makes you think. You know, as I always said, the only thing of value is the thing you cannot say but you can see it, and it grabs you. And that makes the cartoon very important.”

One of the highlights of the whole event was the nearly hour-long conversation I had with Robert Mankoff, the cartoon editor of the New Yorker, and the brilliant illustrator Brad Holland – as the two “agreed to disagree” over a number of points that came up throughout the conversation.

Mankoff was also the only newcomer member of the jury since all the other names had attended the event in previous years, with Holland visiting the country for the third time in nearly two decades. I asked Mankoff if he had any expectations before he arrived, to which he said, “I knew [the entries] would be diverse, from what I call gag cartoons to symbolic ones, resonant with other issues.”

The question followed some previous disagreement over one of the entries, so he smiled, and added, casting a glance at Holland, “I had no idea how diverse the jury would be.”

There were also some warnings regarding the state the country was in.

“It’s funny how people are acting like I’m in great peril, so I’m making jokes, and I’m emailing back, ‘After my Herculean labors and jury duties…’” If it were possible to put it all down on paper, the whole conversation constantly ranged from awesome to even more awesome, and at times rather heated too. The two New Yorkers, who had never met before coming to Turkey, hashed out many aspects of the contest and the art of cartoons, and art in general, and the unlikely emergence of “red carpets” in so many entries. Neither of them had a clue why the image had appeared so strongly, but nearly 10-15 of them carried the theme.

We spoke briefly of the protests, and of the prime minister (“He’s trying to curl back the pages,” Holland told me, “It’s inexcusable”) and eventually came to the topic of humor, a strong component of the Gezi movements.

“Humor is only an opening to me,” Mankoff said. “It’s not an argument. After you make the joke, to convince others, you have to move beyond humor.” Holland mentioned a previous attempt of artists in the U.S. that he led against the copyright laws, in which the artists had suggested drawing pictures and putting them online.

“We stopped the bill, but not by drawing pictures, but by going to the congress. It wasn’t about drawing or cartoons, it was about doing what politicians had to do, and organizing people and fighting on a gut level. It doesn’t mean you don’t do cartoons, you don’t count on the cartoons,” he added.

When Mankoff puts in that the two acts are not mutually exclusive, Holland states, “Yes, they are.”

“Cartoons and political arts are relevant as works of art, or relevant as works of humor. But in terms of accomplishing things, you have to get serious,” Holland added.

Eventually they come to terms with what sort of an impact humor has, which Holland says “could mock the mask of authority, or the corners of the mask and chip away at the platform” right before they drift off to hashing it out a bit more deeply.

“Even beyond politics,” Mankoff says, pointing toward the other end of the bar, “look at those people. They are laughing. The amount of laughter in human conversation is enormous.”

He stops, gesturing toward himself and Holland, he cracks the joke, “Well, not here.”

“We agree to disagree.”