Berberoğlu arrest is forcing limits in Turkey

Murat Yetkin

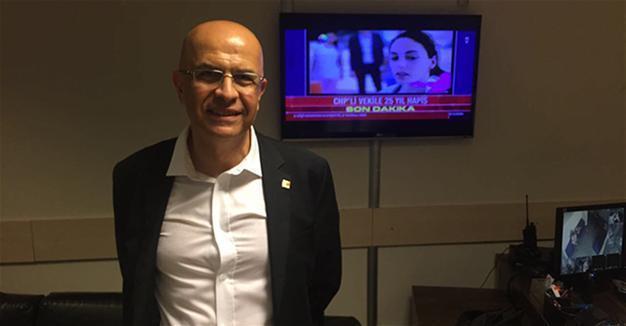

CHP lawmaker Enis Berberoğlu poses for a last photo before being taken to jail as a TV in the background broadcasts the court decision as breaking news. AA photo

Enis Berberoğlu, a member of parliament for the social democratic Republican People’s Party (CHP),

was sentenced to 25 years in jail by an Istanbul court on June 14 and immediately put in prison.

The court ruled that Berberoğlu had “knowingly helped a terror organization” by providing “state secrets” to the media. It is all about the news of how gendarmerie forces stopped Turkish National Intelligence Organization (MİT) trucks on Jan. 19, 2014, as they were carrying military material to Syria.

The arrest of the CHP deputy, who is also the former editor-in-chief of Hürriyet, is a part of a court case in which journalists Can Dündar and Erdem Gül of daily Cumhuriyet are also on trial. Dündar is living in Germany and Gül was together with Berberoğlu when the court read out its ruling. Berberoğlu was accused of providing video material about the search of trucks to Cumhuriyet; the photos and videos were already in the media, but they were placed under restriction afterwards for reasons of national security. The prosecutors, judges and gendarmerie commanders who became involved in the MİT truck operation were either arrested or placed under an arrest warrant for their alleged links with the illegal network of Fethullah Gülen, the U.S.-resident Islamist preacher who is accused of masterminding the July 15, 2016, coup attempt.

Right after the ruling and before being put in jail, Berberoğlu said he was sentenced “without any evidence” and would “get in jail, get out and take those who made the ruling to court.” He said it was journalism on trial.

The CHP has strongly reacted to the ruling. Engin Altay, a spokesman for the CHP, said in front of the courthouse that the ruling was fabricated by “so-called judges who want to please the dictator.” Altay said the ruling was manipulated by the ruling Justice and Development Party (AK Parti), and it aimed to deter opposition in Turkey. In parliament, another spokesman, Özgür Özel, said after an emergency session of the CHP parliamentary group that his party would not “surrender to fascism.”

The fact that he was immediately put in prison, without waiting to provide an opportunity to launch an objection as a member of parliament is forcing the limits of politics in Turkey.

It is difficult to see this example as a purely criminal case; it has political dimensions and it has media freedom dimensions.

The ruling came at a time when Turkey is already under pressure because of journalists and politicians in prison.

I have worked together with Berberoğlu for years as a colleague and as a friend. At one point, he decided to quit journalism and get into politics. As far as I know him and as far as I know Turkish system, I believe he will come out of jail with his head up – although I cannot predict the same thing for those who made the ruling.

Rulings like this are likely to weaken the position of President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and the AK Parti government in their diplomatic ventures, especially with the West.

It is very sad and a shame to report and write commentaries about friends and colleagues put in jail one after another.