No need to get too moody on Turkey

I am used to my forecasts being proven wrong.

Therefore, I was very surprised when a free-fall in Turkish stocks started exactly one week after I wrote my aptly-titled column “

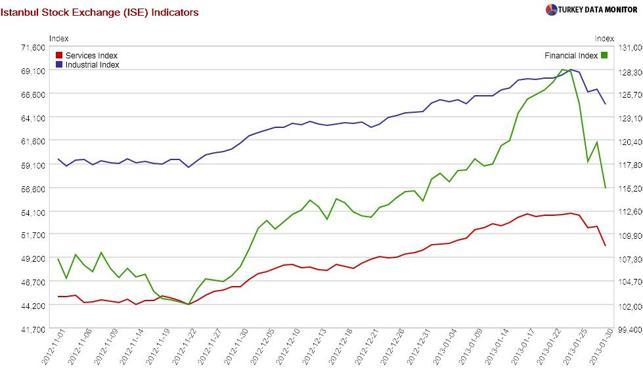

Irrational Exuberance a la Turca.” I argued there that the sharp rise in equities, especially bank stocks, was not based on fundamentals and that there was bound to be a correction soon. But honestly I didn’t expect it to be so soon.

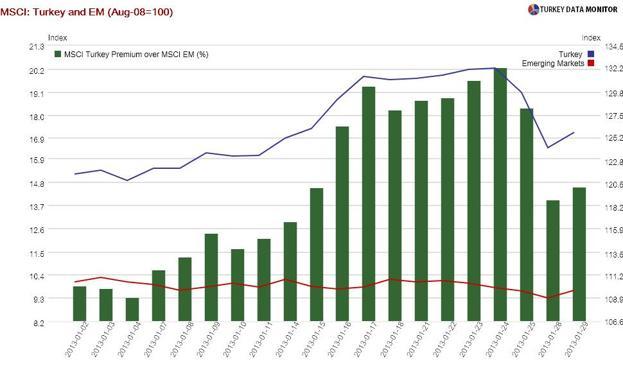

It is true that there was a global risk aversion sentiment this week and the strong capital flowing into emerging markets slowed down. But falling nearly 10 percent from Friday to Thursday, Turkish stocks underperformed peers as well due to several factors.

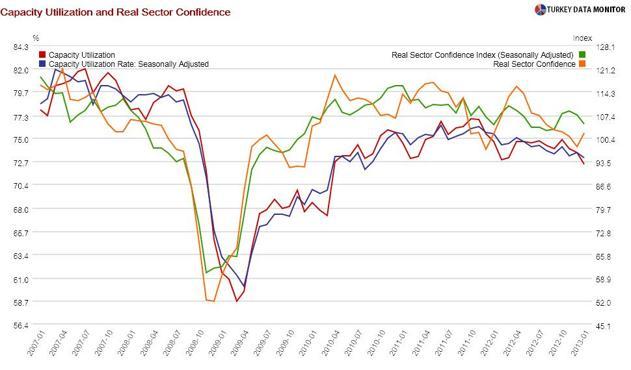

On Jan. 25, the

real sector confidence index and

capacity utilization rate came in lower than expected, hinting that the economy may not be picking up as fast as many analysts are predicting, but the real shockers were seen all this week.

Bank stocks took a hit when Governor Erdem Başçı reiterated in an interview in Davos and during his presentation of the Central Bank’s

Inflation Report on Jan. 29, that the bank was dead-serious about its 15 percent credit growth target for this year. Some individual stocks, such as İşbank and

Turkcell plunged on company-specific news and exacerbated the downfall.

There were also some

technical reasons for the sell-off, which I will detail

over at my blog, but the game-changer of the week was

arguably Moody’s. In a teleconference on Jan. 28, the credit ratings agency reiterated that it would need to see a structural reduction in Turkey’s current account deficit to raise the country’s rating. This is not different from what they said back in November, but it was enough to rattle markets.

There is no need to get moody. After all, Moody’s still expects the current account deficit for 2012 to be 7.6 percent of Gross Domestic Product (GDP). Anyone who remotely follows the Turkish economy has known for a while that the actual number would be more than one full percentage point less than that.

In fact, the

December trade deficit, released on Jan. 30, turned out to be $ 7.2 billion, nearly $ 2 billion lower than expectations. This figure translates into a current account deficit of $ 5.2-5.3 billion. The deficit for the year would then be just above $ 50 billion, or 6.3 percent of GDP.

Unfortunately, the external adjustment has probably come to a halt. That’s where the Turkish Statistical Institute (TÜİK) comes in. As I noted

in my last column, economy tsar Ali Babacan stated in Davos last week that TÜİK was updating its methodology for measuring the current account. He underlined that the rise in annual tourism revenues as a result would be $ 3-5 billion. If a couple of billion dollars comes from exports and imports, the deficit would suddenly fall a full percentage point, to 5.2-5.3 percent.

Turkey would not have solved its dependence on external financing for growth, but at least Moody’s would then have the “excuse” to upgrade the country to investment grade.

I am used to my forecasts being proven wrong.

I am used to my forecasts being proven wrong.