Japan’s (and Turkey’s) J-curse

I have been taking part in the “

tape protests.” Supporters of Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan attacked protesters with döner knives during the summer, so I asked my brother, who was vacationing in Japan, to get me a

katana – so that I can pull a Crocodile Dundee “

that’s not a knife, that’s a knife” act.

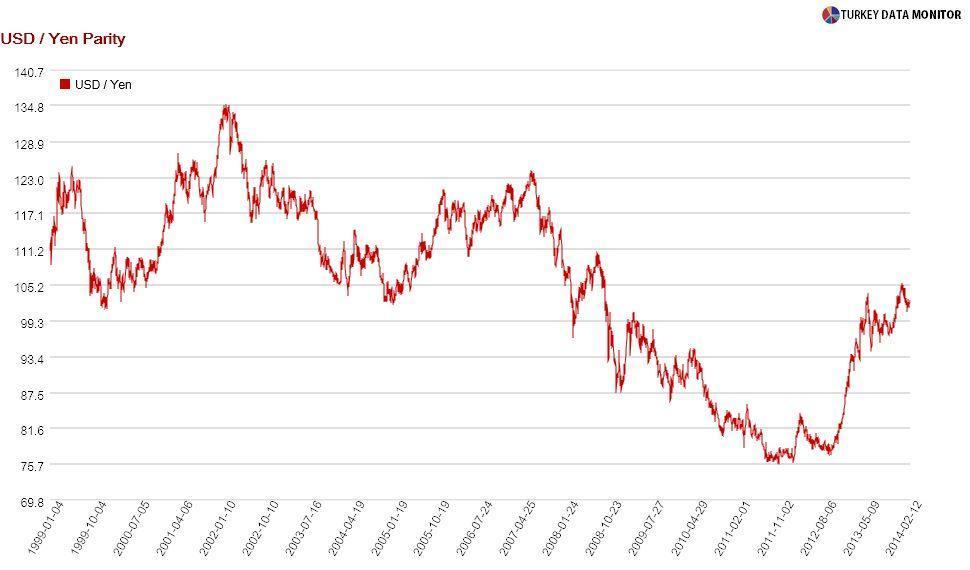

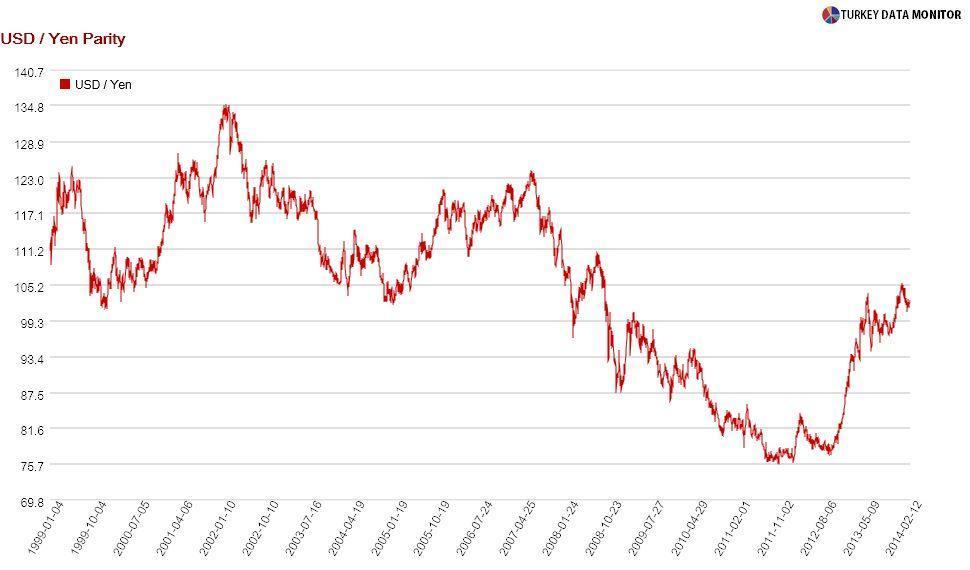

He paid 31,500 yen for it, roughly the equivalent $307. Had he been to Japan one-and-a-half to two years ago, he would have paid $404. The yen has depreciated more than 30 percent against the dollar since the second half of 2012.

The

J-curve effect would tell you that Japan’s trade balance should have eventually improved: A less valuable local currency means imports are more expensive, and so the trade balance worsens initially.

After some time, exports increase, as their lower prices make them attractive. Imports fall at the same time, as consumers buy less of those more expensive iPhones. This volume effect eventually dominates the price effect, and the trade balance improves.

However,

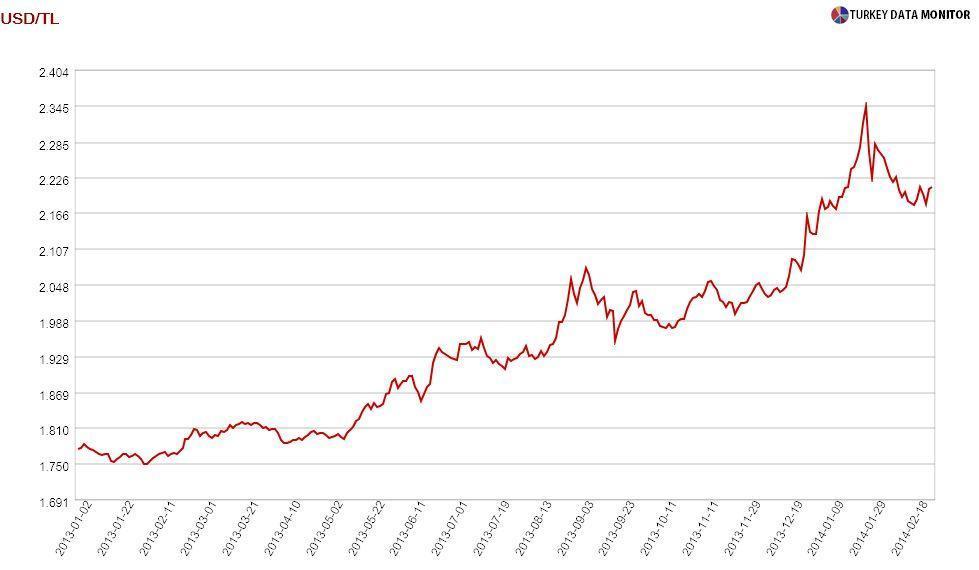

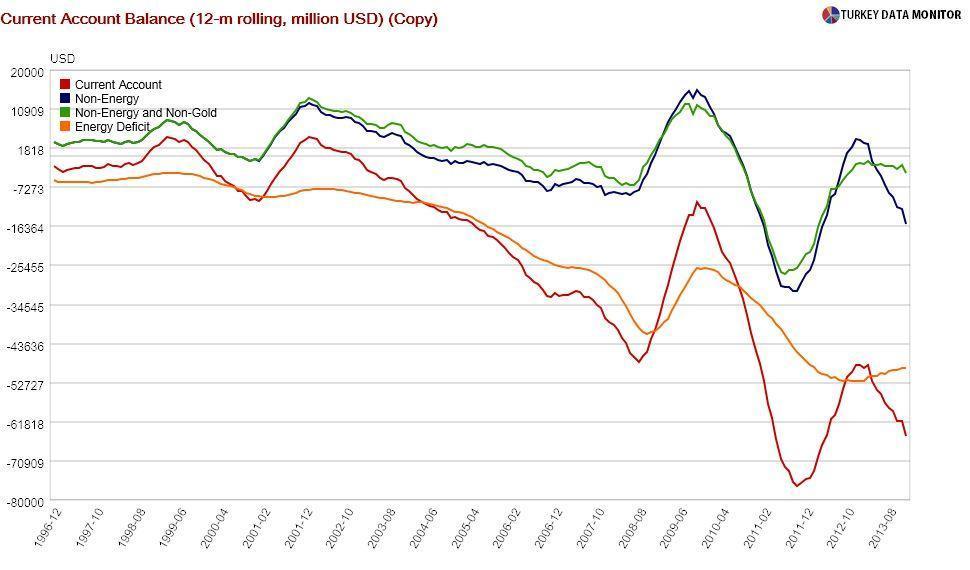

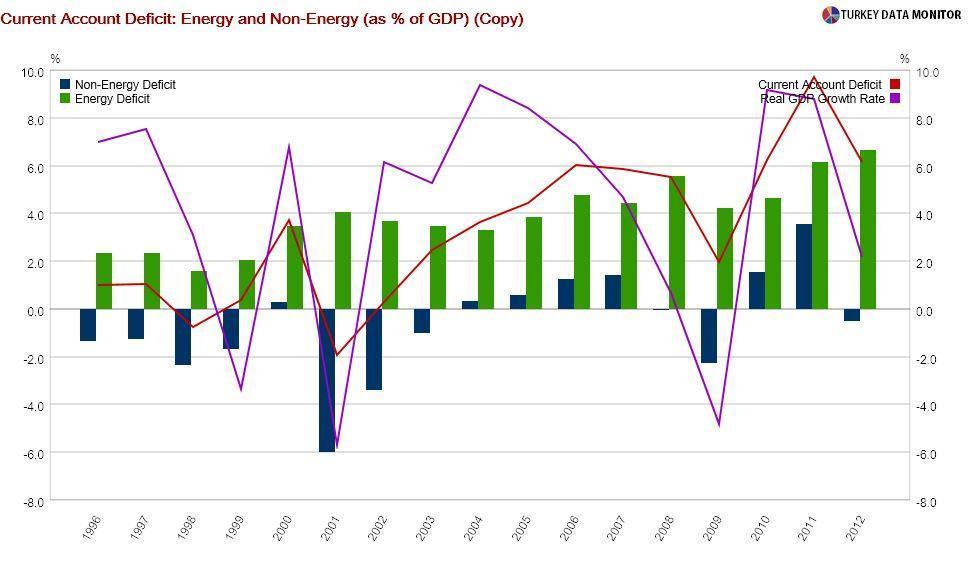

we have not seen such an improvement in Japan. Understanding why may have important implications for Turkey, as the Turkish Lira has depreciated nearly 30 percent against the dollar since the beginning of 2013, building similar hopes of an adjustment in the country’s current account deficit.

Japan, like Turkey, imports a lot of energy, which is obviously insensitive to the exchange rate. Higher gas prices may induce some to drive less, but energy imports cannot just plunge: Even if Erdoğan were to pass a decree requiring everyone to use dried dung for heating, companies would still need fuel.

Ignoring the law against geothermal energy companies, in favor of corrupt corporations from

feudal kingdoms, is not the way to go, but that’s for a future column.

Those of you like me who grew up in the 1980s with Sony Walkmans may find this hard to believe, but the Japanese consumer electronics sector is

suffering from competitiveness – like

many sectors in Turkey. You could argue that Turkish firms will import less intermediate inputs because of the more expensive foreign currency, but a Central Bank survey

found that firms rely on foreign inputs because domestic versions are either unavailable or not of the same quality.

Not all is bleak: Since 30 percent of Turkish exports are to the eurozone, an interest rate cut from the European Central Bank this week, or some sort of a stimulus program later in the year, would help. But the main factor expected to lower the current account deficit is the economic slowdown. However, it seems that the deficit is now less sensitive to lower growth rates, probably because of the reasons I noted above.

I am not claiming that the current account deficit will not improve; it certainly will. In fact, I find the end-year projection of $53 billion in the Central Bank’s survey of expectations way too pessimistic. I am just saying the adjustment may be smaller than expected – despite

signs of rebalancing in the January trade statistics released on Feb. 28.

I have been taking part in the “tape protests.” Supporters of Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan attacked protesters with döner knives during the summer, so I asked my brother, who was vacationing in Japan, to get me a katana – so that I can pull a Crocodile Dundee “that’s not a knife, that’s a knife” act.

I have been taking part in the “tape protests.” Supporters of Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan attacked protesters with döner knives during the summer, so I asked my brother, who was vacationing in Japan, to get me a katana – so that I can pull a Crocodile Dundee “that’s not a knife, that’s a knife” act.