In Turkish towns, especially in the old neighborhoods of Istanbul and the like, the silent darkness of the night is often spiked with a sharp sound yelling “Boza!” It is the piercing sound of a wandering street vendor of boza, a fermented viscous drink, much loved by Turkish people, definitely an acquired taste for foreigners. Boza has a thick viscous consistency, pretty much like a soupy pudding or frumenty, or a thick smoothie. The taste is sweetish yet a bit tart, depending on the fermentation level. Made from millet, wheat, bulgur, rice, or a combination of various grains, it has an earthy, wholesome flavor with subtle yeasty notes. Imagine drinking a yeasty dough in liquid form. It is filling and satisfying, keeps one full for many hours, but it also nourishes the soul evoking a homely nostalgic feeling.

The nostalgic vibe of boza is always there. Perhaps it is because, for many, even the sound of the boza seller pushes the button to recall childhood, the sudden bustle in the house upon hearing the long “boooozaaa” yelling, rushing to the window to call the boza seller, then hurrying into the kitchen to find the containers, the whiff of chilling cold air penetrating in the house, finally sipping the cinnamon dusted boza under the warm blanket while still hearing the fading sound of the boza vendor slowly going afar, that deep down pity felt for him trying to earn his bread for his family in the freezing night, and the gratitude for having a warm home. One may also easily recall the boza vendor in the novel “A Strangeness in My Mind” by the Nobel-winning Turkish writer Orhan Pamuk. In that case, Mevlüt Karataş, the novel’s hero, sells boza as a night job during the cold winter months. In his endless wandering in the streets of Istanbul spanning four decades, he observes the gradual change of the city, the transformation of the old districts, the people and the country in general. Through his eyes, Pamuk narrates how the increasing pace of the world devours the historic essence of the city and how ambitious builders tear down old buildings and replace them with brand-new blocks. Just like the fading sound of the boza seller as he moves on to another neighborhood, our memories of the past slowly grow faint and eventually fade away. Pamuk’s boza seller is the embodiment of lost times, his story an elegy for the long-lost Istanbul. We seldom hear a boza seller deep in the night, though our fondness for the drink is still there, we tend to buy it in supermarkets now.

Boza still survives as a favorite odd drink for people in Türkiye, but the authentic taste of boza might also be a thing of the past. Contemporary boza tends to be more sweetish, while it used to be a bit astringent or sourish. The sourish version was fermented a few days longer, and sometimes had little bubbles coming up, indicating that some alcohol formation was occurring. Strangely, it was not considered an alcoholic drink, Muslims showed no concern about consuming boza, and today boza is innocuous even for the most pious Muslims in the country. There are suggestions that “boza” might be the root of the word “booze” in the English language, folk etymology suggests that the word booze might have its origins in Oriental boza or buza. In Ottoman times a “bozahane” (boza house) was a tavern-like place frequented by sailors, muleteers, porters and other working-class people. The great Ottoman traveler Evliya Çelebi was overwhelmed when he accidentally entered one such place in Ankara, circa the mid-17th century. He described it as filthy with drunken people, definitely not a place for the elite. Though not considered a boozy beverage, there have been several cases where boza houses were banned due to their notorious fame for being hubs of imbibing, and some alcohol-induced fights.

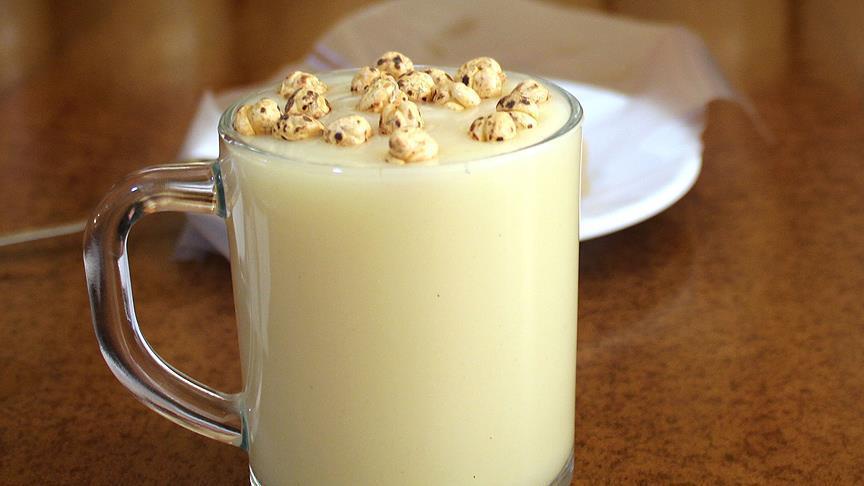

Despite its ill-fame of having a strangeness in mind, the popular belief was that boza gave enormous strength to the drinker. That is why it was mostly favored by the mighty Janissaries, the backbone of the Ottoman army; so much so that they carried boza-makers with them on their campaigns along with saddlers, farriers, cooks and barbers. The Ottoman court also favored boza, copious amounts were obviously made in the palace kitchens, according to registrars, the rice bought for boza-making only amounted to seven and a half tons in the fiscal records of 1631. One might argue that the Sultan favored it for that “strength” giving properties of boza. The strength-giving aspect is actually true, boza is like a power drink that boosts energy. There is also the slight lulling effect, again because of the rich carbohydrate boost coming from the grains, and also that hidden boozy content in the sourish ones. That is the source of strangeness in the mind that inspired Pamuk’s novel. Nevertheless, the thought that it is good for health surpassed the concern of hidden booziness in the beverage, and it was interpreted as a sleep-inducing winter delight, even fit for the kids. In today’s shift to sweetness in boza is not that people fear the soured ones to keep safe from “the strangeness in mind” but it is because our taste palette has tilted to the sweet, rather than the pungent, acrid or acidic tastes. Whether you prefer the sweeter or sourer versions, a small cup of boze is a must-try strange taste that we like, always with a good sprinkling of cinnamon and a handful of roasted chickpeas floated on top!