The fall of the Turkish model

William Armstrong - william.armstrong@hdn.com.tr

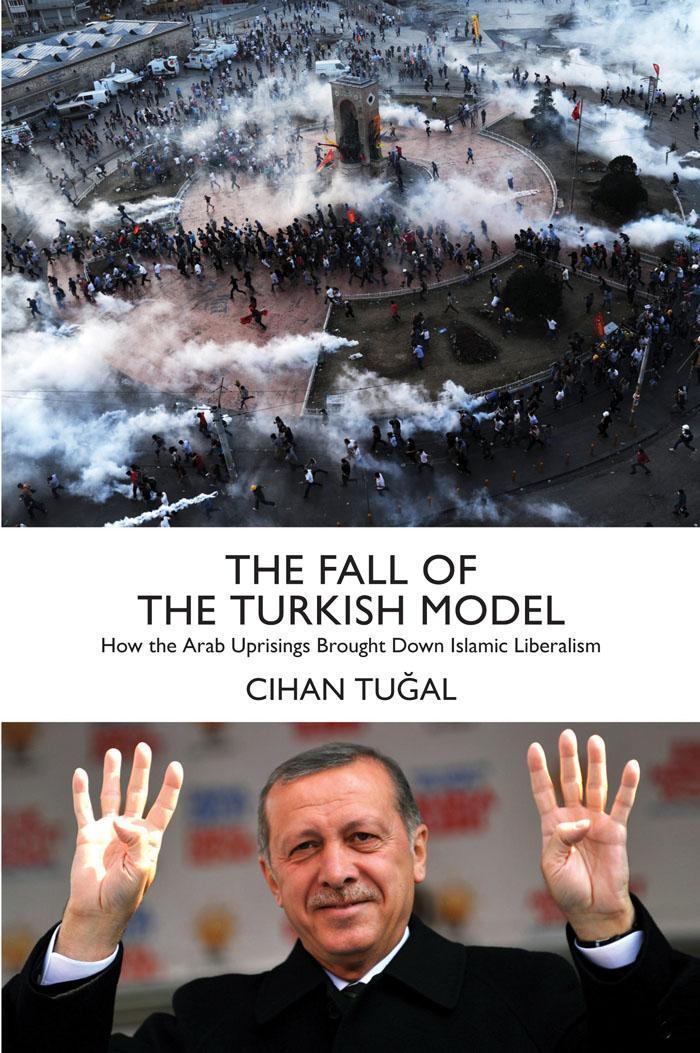

‘The Fall of the Turkish Model: How the Arab Uprisings Brought Down Islamic Liberalism’ by Cihan Tuğal (Verso, £20, 304 pages)

‘The Fall of the Turkish Model: How the Arab Uprisings Brought Down Islamic Liberalism’ by Cihan Tuğal (Verso, £20, 304 pages)What went wrong in Turkey? Ten years ago, the world was fawning over the “Turkish model.” The Justice and Development Party (AKP) and its leader Recep Tayyip Erdoğan were praised as democratic pioneers. Turkey was said to be pioneering a marriage of democracy, free market capitalism and pragmatic Islam. Global business circles trumpeted the model, media celebrated it, regional and national elites embraced it, and academics were on board. Turkey was said to be providing a successful template for other Muslim majority countries to apply. Even up to early 2014, Pollyannaish books were still being published about

“The Rise of Turkey.”

Today the mood is very different. The orgy of praise that showered the Turkish government has turned 180 degrees. It is now looks increasingly like a pile-on, with no criticism too outlandish to get an airing. Reading much of the analysis, you get the impression that Erdoğan changed overnight from great democratic reformer to authoritarian despot. Although they once basked in global adulation, government officials now reap the domestic benefits of Western opprobrium: For Erdoğan’s supporters, critical reports in the international media prove that there is a global conspiracy against Turkey’s rise to greatness.

The idea of the

“Turkish model” has roots going back to the start of the Cold War. Plenty of post-mortems have been written for it; no doubt they will continue to be written. “The Fall of the Turkish Model” by UC Berkeley sociologist Cihan Tuğal is the first book-length treatment of the subject. Tuğal takes a longer structural view, arguing that “the successful liberalization in Turkey during the last three decades itself paved the way for Islam’s later authoritarian and conservative incarnations.” Tackling the question from the left, he writes that the cause of Turkey’s crisis was “the neoliberal-liberal democratic model (rather than Erdoğan the villain – or, for that matter, ‘Turkish culture’).”

The book links the final collapse of the Turkish model to the Arab uprisings of 2011. That is ironic because it was then that the model was hawked around the Middle East so keenly. A version of “moderate Islamism” was said to be the natural hegemonic course for regional states emerging from under the control of repressive “secular strongmen.” Through case studies of Egypt, Tunisia and Syria before and after 2011, Tuğal aims to show how the model was actually never exportable in any meaningful sense. “The AKP’s current hegemony, as we have seen, rests on a very specific conjecture of mobile class forces, state structures and cultural traditions,” he writes. Not least of those is the country-specific network of graft and kickbacks orchestrated by the

political authorities.

The government’s attempts at regional hegemony after 2011 were full of strategic blunders and wishful thinking. Conditioned by Turkey’s internal dynamics, Ankara insisted on interpreting the region according to non-generalizable local phenomena. However, the uprisings “dynamited the potentials for peaceful liberalization along the lines of the Turkish model,” Tuğal writes. “The Muslim Brotherhood’s various passive revolutionary moves further undermined the basis for the replication of the Turkish scenario across the Arab world.” As the uprisings and regime changes unfolded, Turkey shifted further to the right and flirted with sectarianism, torpedoing the “liberal-Islamic” Turkish model.

This process was exacerbated by Turkey’s own anti-government “Gezi” protests in the summer of 2013. The government’s iron-fisted response to the protests hammered one of the final nails in the coffin of the liberal-Islamic coalition power bloc that sustained the AKP for 10 years. “Whereas consent outweighed force before the revolt, now the importance of force in the balance increased,” Tuğal writes. The government destroyed much of its professionalism as it resorted to crude populism to consolidate its base against the protests, desperately clinging to its monopoly of power. Tuğal suggests the largely middle-class Gezi protests also exposed a wider “crisis of liberalism,” claiming that “the new middle class has a love/hate relationship with free market capitalism even in the most successful neoliberal cases.” This, he says, is not only valid for the Arab uprisings but also the wider wave of global protests since 2009 shaking Iran, Greece, Iceland, the U.S., Spain, Brazil, Ukraine, etc. At times Tuğal sounds like a Turkish version of Paul Mason, enthusiastically spotting capitalism’s demise in every global revolt.

The intensity of the anguish in the West over Turkey’s authoritarian descent is partly due to what that failure says about the West itself. It has been suggested that the “Turkish model” in its various forms has always

“revealed more about U.S. anxieties in periods of geopolitical turmoil than about Turkey itself.” Today, the collapse of the Turkish model may demonstrate the non-inevitability of democratization in litmus-test states - and perhaps indicates limits to the ability of the U.S. to effectively export the “American way.”

Still, whatever Western elites or left-wing headshakers think about it, neither Erdoğan nor his government acknowledges the Turkish model’s failure. Though Turkey has gone from “strategic depth” to “precious loneliness,” officials continue to insist they are on the right side of history - and plenty believe that God is on their side. They say the car crash of the last few years is only temporary and Turkey continues to shine as a beacon to the region. It remains to be seen where this insistence will lead; the signs certainly don’t look good.

*Follow the Turkey Book Talk podcast via iTunes here, Stitcher here, Podbean here, or Facebook here.

‘The Fall of the Turkish Model: How the Arab Uprisings Brought Down Islamic Liberalism’ by Cihan Tuğal (Verso, £20, 304 pages)

‘The Fall of the Turkish Model: How the Arab Uprisings Brought Down Islamic Liberalism’ by Cihan Tuğal (Verso, £20, 304 pages) Today the mood is very different. The orgy of praise that showered the Turkish government has turned 180 degrees. It is now looks increasingly like a pile-on, with no criticism too outlandish to get an airing. Reading much of the analysis, you get the impression that Erdoğan changed overnight from great democratic reformer to authoritarian despot. Although they once basked in global adulation, government officials now reap the domestic benefits of Western opprobrium: For Erdoğan’s supporters, critical reports in the international media prove that there is a global conspiracy against Turkey’s rise to greatness.

Today the mood is very different. The orgy of praise that showered the Turkish government has turned 180 degrees. It is now looks increasingly like a pile-on, with no criticism too outlandish to get an airing. Reading much of the analysis, you get the impression that Erdoğan changed overnight from great democratic reformer to authoritarian despot. Although they once basked in global adulation, government officials now reap the domestic benefits of Western opprobrium: For Erdoğan’s supporters, critical reports in the international media prove that there is a global conspiracy against Turkey’s rise to greatness.