Cyprus: A Modern History

William ARMSTRONG - william.armstrong@hdn.com.tr

‘Cyprus: A Modern History’ by William Mallinson (I.B. Tauris, £15, 242 pages)

‘Cyprus: A Modern History’ by William Mallinson (I.B. Tauris, £15, 242 pages)The central theme of this book is that Cyprus has always been a “cat’s paw” of outside powers. The subtitle of Christopher Hitchens’ 1984 book on Cyprus was “Hostage to History,” but the author of this lively and opinionated title, former British diplomat William Mallinson, suggests that “hostage to hypocrisy” would also be apt. Generally outside the radar of international media attention, Aphrodite’s island has given the poker players around the table a unique arena for double dealing and skullduggery.

Mallinson’s strongest ire is reserved for Britain’s miserable performance on the island. As the great Perry Anderson has written: “In the modern history of the Empire, the peculiar malignity of the British record in Cyprus stands apart.” Taken under British suzerainty in 1878, and with British military and intelligence facilities dotted around the island, Cyprus has long been London’s key strategic foothold in the Eastern Mediterranean, its “main Middle East headquarters.” As former British Prime Minister Anthony Eden wrote in a (less than) diplomatic note in 1956: “No Cyprus, no certain facilities to protect our supply of oil. No oil, unemployment and hunger in Britain. It is as simple as that.”

In addition, with any vacuum likely to be filled by the Russians, the geopolitical paradigm after World War Two was crucial in shaping British - and later American - policies. Fear of Russia was the reason Britain first occupied Cyprus in 1878, and although the island gained what Mallinson describes as an “adulterated independence” in 1960, Cold War imperatives were already well established. These would prove to be a far greater determinant of Cyprus’ future course than the internal dynamics of the island itself. The prospect of enosis (union with Greece) waxed and waned, but such unification was explicitly forbidden in the botched constitution that Cyprus was lumbered with, as was partition. In the end, the various players’ varying approaches to enosis or partition never coincided to create the kind of momentum that would tip the balance decisively in favor of one or the other. Indeed, the British had disregarded a referendum held after the Greek Civil War that found 96.5 percent of Greek Cypriots in favor of enosis.

After “independence,” the U.S. interest in Cyprus increased exponentially as Britain’s declined (though not the latter’s ability to blunder). Washington wanted to avoid any upset in NATO’s southern flank, but somewhat cutting against this grain was Britain’s calculation that the best way to protect its own interests on the island and prevent enosis was to pursue a policy of division. This essentially involved secretly colluding with the Turks both on the island and in Turkey. “Buttons were pushed” in Ankara to raise Turkey’s awareness and proprietorship over the Turkish Cypriot community, and the British helped to cement division by encouraging the establishment of a large Turkish Cypriot police mobile reserve in Cyprus, “let loose for savagery when the occasion required.” As Britain’s ambassador in Ankara cynically advised the Labour government in London at the time: The “Turkish card” was “useful in the pass to which we have come.”

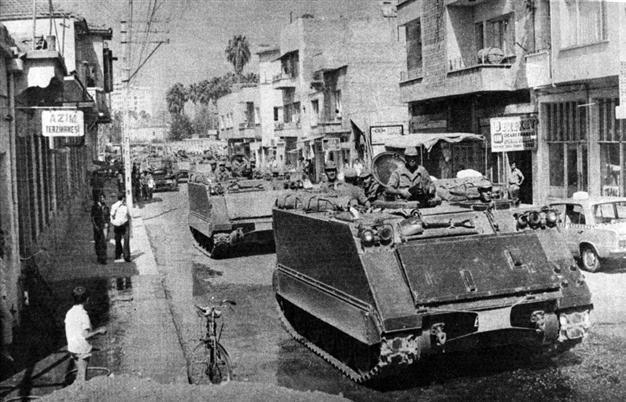

The logical – if extreme – extension of this policy came to pass with the catastrophic Turkish invasion of the island in 1974, after a coup in Cyprus in 1973 that had brought a hardline administration to power, (with the alleged support of Henry Kissinger and the CIA, keen to oust the non-aligned Cypriot leader Michael Makarios). Mallinson describes the illegal Turkish invasion as a “brutal affair,” in which more than 200,000 Greek Cypriots were driven south, most Turks in the south were driven north, and over 5,000 Greeks and over 1,000 Turks were killed or went missing. To this day, the Turkish army maintains 35,000 soldiers in the occupied zone, and 100,000 mainland Turks have settled in occupied North Cyprus. Both of these ratios exceed the number of Jewish settlers and Israeli soldiers deployed in the West Bank, with hardly a word of protest from the Council of Europe or the European Commission.

The bulk of the pertinent “backstage” diplomatic evidence since 1975 has still yet to be released, which is a slight hamstring for Mallinson, who bases most of his book on scrupulous study of the British and U.S. diplomatic record. A quisling Turkish government was established in Northern Cyprus in 1983, Turkish migration has altered the demographic balance, and the South’s accession to the EU (enormously short-sighted) was completed in 2004; but the diplomatic situation has essentially been in stalemate since 1974. All rounds of negotiations have come to little, “matters inevitably boil down to the Greek side insisting on compliance with U.N. resolutions, while the Turkish side insists on recognition for Northern Cyprus before substantive talks can begin,” Mallinson writes.

One of the drawbacks of this book is that while the author has a thorough knowledge of the British and U.S. diplomatic sources, he leaves the Cypriot, Greek and Turkish papers almost untouched. But if Cyprus is overwhelmingly acted upon rather than an independent actor itself, perhaps this method serves a useful rhetorical purpose. The latest peace talks on the island began in February this year, amid optimism that U.S. pressure, spurred by the discovery of oil and natural gas reserves in the Eastern Mediterranean, could shift the diplomatic paradigm. That remains to be seen; if the historical record is anything to go by, nobody should hold their breath.

‘Cyprus: A Modern History’ by William Mallinson (I.B. Tauris, £15, 242 pages)

‘Cyprus: A Modern History’ by William Mallinson (I.B. Tauris, £15, 242 pages) In addition, with any vacuum likely to be filled by the Russians, the geopolitical paradigm after World War Two was crucial in shaping British - and later American - policies. Fear of Russia was the reason Britain first occupied Cyprus in 1878, and although the island gained what Mallinson describes as an “adulterated independence” in 1960, Cold War imperatives were already well established. These would prove to be a far greater determinant of Cyprus’ future course than the internal dynamics of the island itself. The prospect of enosis (union with Greece) waxed and waned, but such unification was explicitly forbidden in the botched constitution that Cyprus was lumbered with, as was partition. In the end, the various players’ varying approaches to enosis or partition never coincided to create the kind of momentum that would tip the balance decisively in favor of one or the other. Indeed, the British had disregarded a referendum held after the Greek Civil War that found 96.5 percent of Greek Cypriots in favor of enosis.

In addition, with any vacuum likely to be filled by the Russians, the geopolitical paradigm after World War Two was crucial in shaping British - and later American - policies. Fear of Russia was the reason Britain first occupied Cyprus in 1878, and although the island gained what Mallinson describes as an “adulterated independence” in 1960, Cold War imperatives were already well established. These would prove to be a far greater determinant of Cyprus’ future course than the internal dynamics of the island itself. The prospect of enosis (union with Greece) waxed and waned, but such unification was explicitly forbidden in the botched constitution that Cyprus was lumbered with, as was partition. In the end, the various players’ varying approaches to enosis or partition never coincided to create the kind of momentum that would tip the balance decisively in favor of one or the other. Indeed, the British had disregarded a referendum held after the Greek Civil War that found 96.5 percent of Greek Cypriots in favor of enosis.