Lumini ex orient: Solution to Turkey’s problems?

Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s statement about the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) has become a trending topic in Turkey over the last two weeks. In response to a question on Turkey’s accession negotiations with the EU, he said, “When things go wrong in such a way, you…end up looking for other options. That’s why I recently said to Mr. Putin: ‘Take us into the Shanghai Five and we will say farewell to the EU.” Although the real intention of the Prime Minister is yet to be revealed, his statement prompted analyses that this was a warning to the EU and indicated a policy shift in Turkey’s international orientation; hence a possible axis shift.

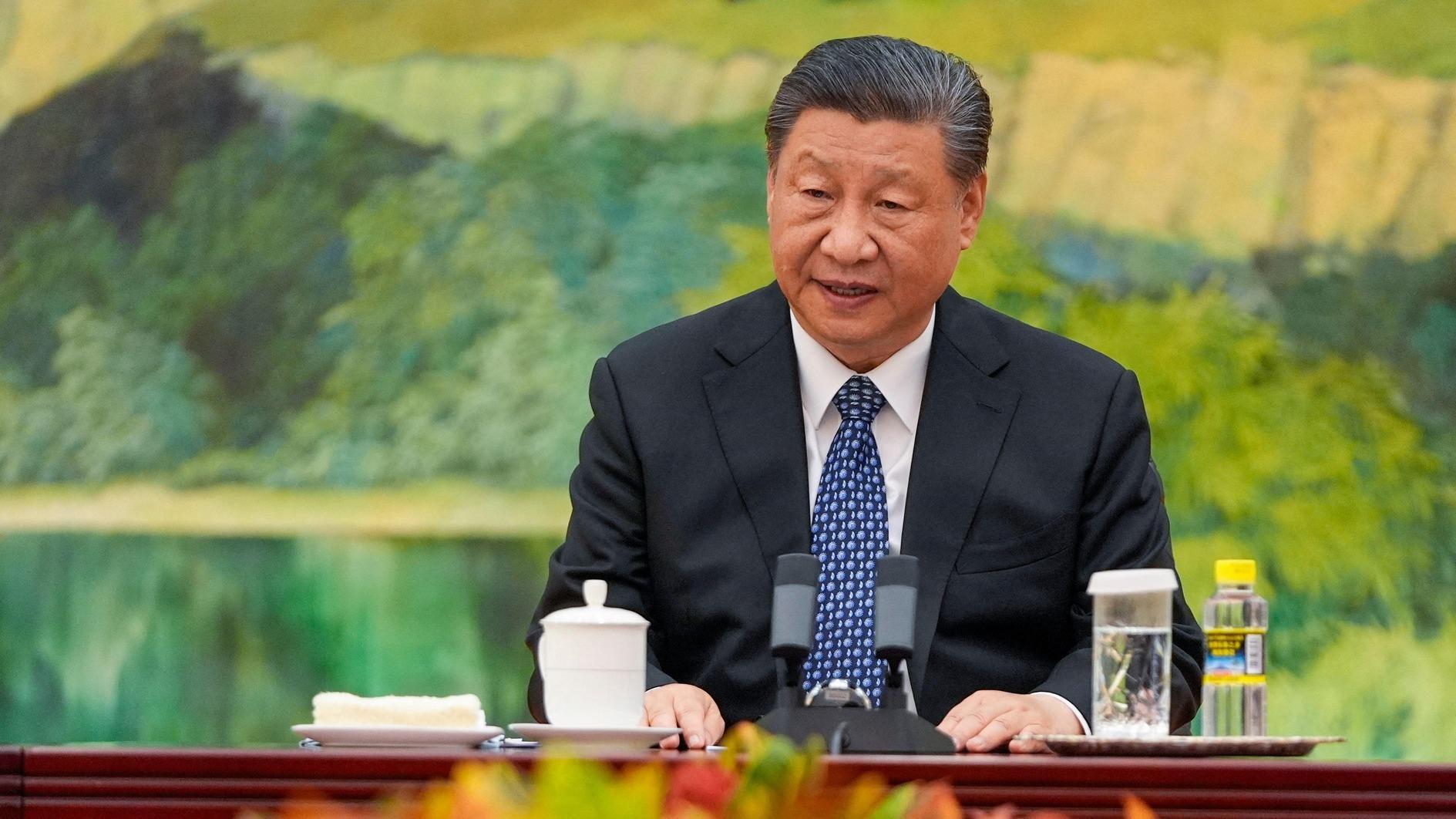

The Shanghai Five was founded in April 1996 with the signing of the “Treaty on Deepening Military Trust in Border Regions” by the leaders of China, Russia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan. The initial suggestion for such an entity came from China and its call on its Central Asian neighbors to stop the movement of its Muslim-Turkic minorities, whom Chinese leadership labeled as extremists, across their common border. On the other side, Central Asians, wishing to solve their border demarcation problems with China left behind by the demised Soviet Union, but not willing to stand alone against Chinese military might, proposed a series of regional cooperation meetings with China and Russia; the latter of which was thought to be a counterweight against the former. After Uzbekistan joined the gathering in July 2001, it was transformed to an international organization and renamed.

By this time, Russia, recovering from its earlier weaknesses in the region, was trying to remodel the gathering towards a mutual security cooperation organization. The sudden American move into the region as part of its “war on terror” following the 9/11 attacks gave additional impetus to Russia and China to tighten the SCO’s rationale and position it as a counterweight to American influence in central and east Asia. Since then, the SCO members expanded their cooperation areas from security to economy, politics, culture, energy, etc. However, most of the declared aims remained on paper and, except stabilizing the border areas, its effectiveness remained low.

The EU, on the other hand, is a totally different entity. Admittedly, it was also established with an aim to end centuries-old distrust and animosity between European nations. But it has successfully evolved into an economic and political organization. Though it also tries to develop a military arm, the responsibility to provide security to Europe (especially the hard type) is mainly left to NATO. Besides, the underlying integrationist streak within the EU sets it apart from any other organization.

Faced with repeated refusals and delays at the gates of Europe, it is understandable that some people in Turkey might wish to explore alternatives. Also, it is a time-honored tradition in Turkish (and Ottoman) diplomacy to play powers to each other and try to balance them. There is nothing wrong in developing various connections around the world simultaneously in an attempt to widen Turkey’s reach in the international arena. The SCO can be such an option as the Asia-Pacific is becoming more important in global politics.

Yet thinking this connection is an alternative to Turkey’s European connection is a fallacy. The values, such as democracy, human rights, freedom of thought and many others, that are securely attached to the EU but mostly avoided in the SCO, are powerful stimuli not to do so.

Looking from any angle, there is no comparison between the SCO and the EU. If we wish to imagine the SCO an alternative to something, it is NATO, not the EU. Does Turkey wish to leave NATO and become a member of the SCO instead? I very much doubt so.