Photographer wants to keep analog photography alive

ISTANBUL

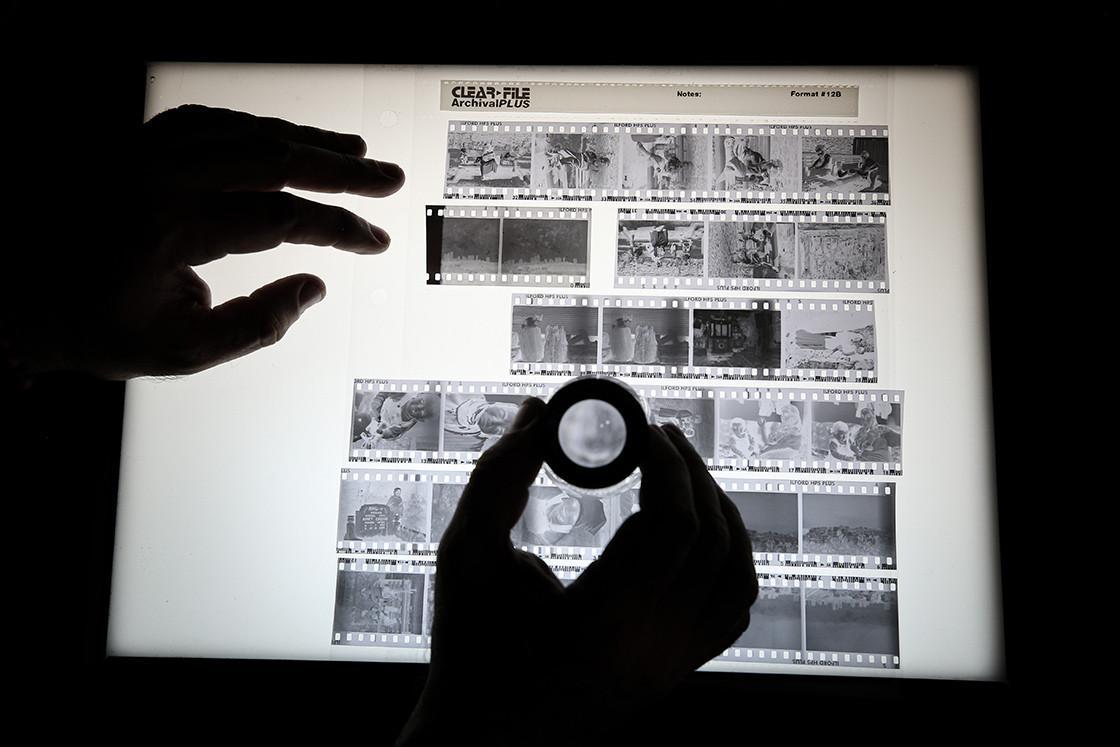

Selçuk Coşkun refuses to switch to digital photography. In his small shop in Istanbul’s Sirkeci neighborhood, the heart of analog photography in Turkey, Coşkun develops films and keeps the once dying practice alive.

Coşkun started analog photography by purchasing an analog camera in the early 1990s. He learned the techniques of photo washing and printing by receiving training from many experts in this profession. Analog photography requires patience, care and effort, all three things Coşkun has excelled in. He also worked in many fields that require high-level expertise, including advertising, fashion and architectural photography.

He worked many times with Turkey’s world-renowned master photojournalist Ara Güler, printed Güler’s famous photo series “Porters” “God and Woman” and “Golden Horn’s Fishermen.” By resisting the digital transformation in photography and cinema after the 2000s, Coşkun wants to pass down his profession to future generations.

Coşkun continues to wash and print the films of photographers devoted to analog photography. He has become one of Turkey’s stewards keen on keeping the practice around for many decades to come.

Expressing his interest in photography since childhood, Coşkun told state-run Anadolu Agency that he took his first step in the sector with Mehmet Kısmet, the founder of the Istanbul Photography Center, and that he had been trained at the center for years.

Coşkun stated that he continued to go to school and work, and said, “Analog photography is hard work. It was even more difficult, especially in the advertising business. Of course, you cannot see what you are shooting first. You measure it with a light meter, then you can see what you took with a polaroid. You see its light and the setting. If appropriate, you transfer it to the film. Then you patiently wait for what the photo looks like. Washing and printing are the excitement of this job. It is actually very difficult not to see what you photographed. You integrate with the machine. In digital photography, you can constantly look and delete a photo. There is a serious difference in feelings between these two.”

Referring to the worldwide digital transformation in photography and cinema especially after 2010, Coşkun said that almost all of his colleagues started to do other works in the transformation process.

Coşkun said that even in Sirkeci, which has had a prestigious place among the analog photography centers of the world for many years, the number of people interested in analog photography is very low.

“Sirkeci certainly is the center of photography developing in Turkey, maybe even in the world. But the number of people working in this market like me does not exceed 10 anymore. We love this job. There are, of course, its enthusiasts. There are also those who develop films at home. It doesn’t cost much. We help them with whatever it takes. Here I am trying to teach this profession to young people.”

Coşkun pointed out that the interest in analog photography has increased especially among young people in recent years and this interest has caused the difficulty of finding equipment.

Coşkun evaluates the increase in the interest in analog machines as “longing for nostalgia.”

“There are very few people who develop films, but the number of young people taking photos has been on the rise for several years. Analog machines are hard to find because they have been popular among young people. Especially young people born in 2000s are incredibly curious. This interest makes me happy. It is nice to see young people here. I am trying to explain this job to young people who come here so that my profession does not die. Young people want results immediately,” he said.

“They are really impatient. But here they learn patience and effort.”