The end of high growth?

This is the end of high growth rates for the world economy, at least for a time. Some East Asian countries will naturally continue to enjoy rapid growth, although not as much as before. The biggest question is how long other parts of the world can prosper when developed and emerging economies both stagnate. To answer that, it is necessary to make a comparative analysis of the world economy.

Let us begin with the United States. After the incomplete fiscal cliff agreement, there is widespread curiosity about the future of the economic policies implemented so far by the administration. Will there be any changes? If there are, will they be big or small? Alternatively, is there a possibility that business will go on as usual? There are some hints that the policies will change a lot if Congress gives its assent. The Federal Reserve Bank recently gave a signal that it will end its monetary easing policies. Is it because of a fear of a new inflation surge, or is it hidden political support for President Barack Obama for an expected fiscal showdown in Congress?

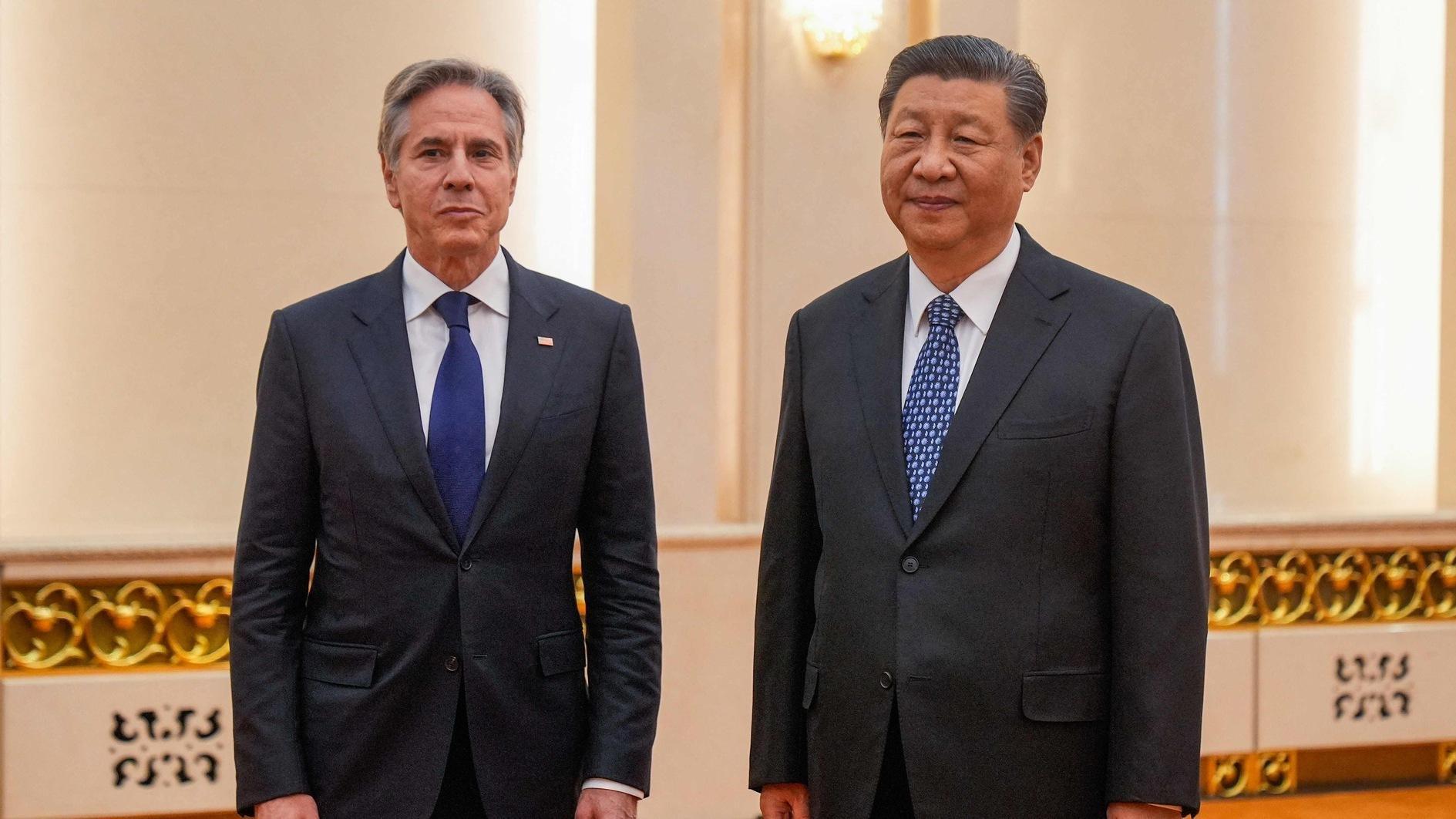

The world’s second largest economy, China, is dealing with the negative impacts of the European slowdown and very slow recovery in the U.S. economy in addition to political transition problems. The Economist Intelligence Unit forecasts 8.5 percent growth for 2013 – better than last year, but worse than the last decade’s average. However, there is still discussion as to whether China will overtake the U.S. and become the biggest – not the second biggest – economy in the near future. If both countries’ growth rates are taken into account, simple mathematics and linear projections dictate that this is not impossible.

However, even if the mathematical method is simple, the economic, social and political problems of emerging countries are not so simple; instead, they are very complex. And the complexity of these problems generally creates serious obstacles to sustainable, high growth rates. Nevertheless, the contribution of their combined growth to the recovery of the world economy is more important than the race between them. If this contribution is weak, nobody cares which of them will be the leading economy.

In Europe, in spite of the continuation of the economic slump, finance ministers have defended austerity measures in order to fight against the deficit and debt problems of some EU member countries. The euro slides downward from time to time because of new bailout stories and the fear of the spread of the sovereign debt crisis. The other serious problem concerning the European economy is the two different approaches of the European Central Bank management. While one group favors anti-inflationary policies, the other seeks to pursue the implementation of recovery policies until the end of the crisis. The main reason for this divergence might be the differences between inflation rates within the eurozone.

Although the International Monetary Fund has cut Japan’s growth forecast (which was already not very bright), the Asian Development Bank forecasts high growth for Asia but a further deterioration of income distribution. According to the bank, rising food prices have particularly sent more people into poverty. This might create new social and political problems in the region. Forecasts for the Latin America region are not very bright. The leading economy in the region, Brazil, has some political problems in addition to economic ones.

There are so many other problems in the world economy to discuss. However, it is not reasonable to become overly pessimistic. There have always been ups and downs in the world economy, as in world politics. In short, growth rates in every region will be modest not only in 2013 but also during the coming years. The million-dollar question is whether this is the end of high growth rates for a long period of time or just a temporary halt stemming from the 2008 crisis.