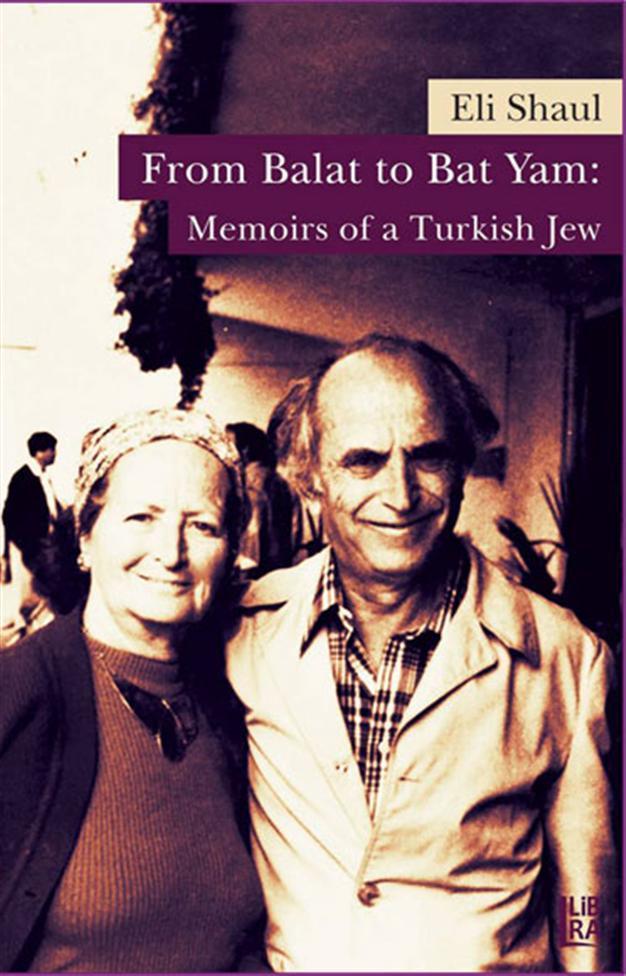

‘From Balat to Bat Yam: Memoirs of a Turkish Jew’ by Eli Shaul

William Armstrong - william.armstrong@hdn.com.tr

‘From Balat to Bat Yam: Memoirs of a Turkish Jew’ by Eli Shaul (Libra Books, 2012, 50 TL, 243 pages)

‘From Balat to Bat Yam: Memoirs of a Turkish Jew’ by Eli Shaul (Libra Books, 2012, 50 TL, 243 pages)“From Balat to Bat Yam” is one of a number of valuable titles on Istanbul’s Jewish community in the 20th century from the tiny Libra publishing house. The print runs for these books are so miniscule that their subjects are not likely to be much less obscure than they were before, but they always offer satisfying food for thought. Eli Shaul was born in 1916 and grew up in Istanbul’s Balat neighborhood, before moving over the Golden Horn to Galata and then migrating to Israel with his family in 1950. Thousands of Turkish Jews have experienced a similar trajectory, but not everyone left behind such a varied and stimulating written record as Shaul.

The book is divided into six main sections, which together make up a kind of compendium of Shaul’s life. They were all written at different times and for different purposes, ranging from an account of his memories growing up in Balat, to extracts taken directly from his personal diary at high school and university, to later ruminations on political and social conditions in Turkey and the world. Particularly notable among the latter are those pieces that he wrote addressing the notorious Wealth Tax that was levied during the war, ostensibly to prevent black market profiteering but in practice punitively imposed on Christians and Jews. If individuals couldn’t come up with what they “owed,” they were sent off to the remote Anatolian labor camp of Aşkale. At the time, Shaul was performing his military service as a reserve officer in the eastern town of Doğubeyazıt in 1943, and could only observe from afar as his father was assessed 5,500 liras of Wealth Tax. In the end, the family was able to rally friends and relatives to come help with the payment, but the experience made Shaul’s father “forget what it meant to laugh and be happy,” and he died soon after in 1949.

The Wealth Tax was perhaps the single biggest reason why Jews and other minorities threw their support behind Adnan Menderes’ Democrat Party in the republic’s first free elections in 1950. Shaul writes that being a Jew meant being for the Democrat Party, and he is a formidable critic of the “blatant racism” of the Republican People’s Party (CHP) during the previous single party period: “In my opinion – and in everyone’s opinion – the word ‘Nationalism’ from the CHP’s six arrows was just an updated and embellished form of the word ‘Racism.’” In one striking passage, he complains to an army colleague about the exclusion of non-Muslims from the civil service, and gets the following reply: “Yes, these things are true, but before the war [1914-1918] the situation was just the opposite. Now it’s your turn to suffer and see injustice.” This kind of stubborn zero-sum logic has proven remarkably persistent in various political guises through the years in Turkey.

Shaul became an unswerving advocate of Zionism, and was one of the founders of the organization “Ne’emanei Tsion” (Loyal Lovers of Zion) in Istanbul in 1934. He penned articles on the subject in the Jewish press in Turkey, even after emigrating with his family to the Israeli coastal town of Bat Yam in 1950. Like many others at the time, throughout these pieces there’s barely a thought for the Arabs displaced in the process of founding Israel, the ensuing refugee crisis, or the trouble this was storing up. Much better, however, are the indignant letters that Shaul penned around the same time to Cevat Rıfat Atilhan, one of the most prominent Turkish anti-Semites in the late 1940s: “You, esteemed Cevat Rıfat, may be … an apprentice of Hitler, but you are no Master. Because he killed those six million Jews, but you can’t even kill six Jews.”

“From Balat to Bat Yam” sits well alongside the growing number of similar, modest titles published by Libra. Shaul’s life may well have been fairly “ordinary,” and his experiences not greatly different to many other Istanbul Jews born around the same time, but it’s a 500-year-long ordinariness that is close to disappearing today.

Notable recent release

‘A History of Jewish-Muslim Relations: From the Origins to the Present Day,’ edited by Abdelwahab Meddeb and Benjamin Stora

(Princeton University Press, $75, 1152 pages)