Afghans fret flight of hard cash sign of things to come

KABUL - Reuters

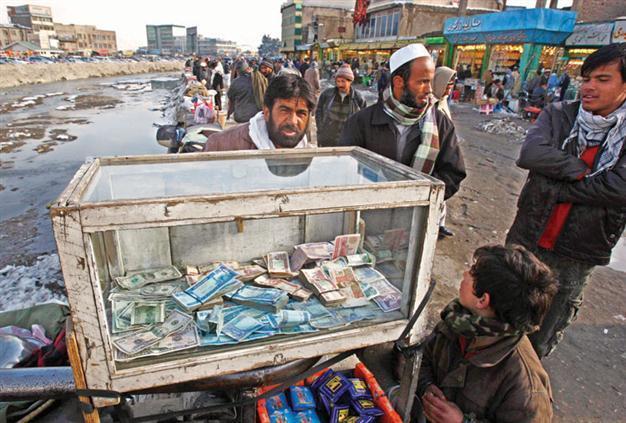

An Afghan money changer works at a market in Kabul in this file photo. Afghan officials are thinking hard about how to stop the flight of foreign currency. REUTERS photo

In the crush of people in Kabul’s Shahzada money market, conspiracy theories are a currency as hard as the bundles of cash in the hands of bearded traders trying to divine their future.And the theory going around - amid the din of shouted exchange rates - is that Afghanistan’s rich are preparing again to shift their money and lives from the country over fears of chaos or civil conflict after foreign troops leave.

“The money will all go out of Afghanistan. It is always like that. As soon as the foreign soldiers leave all the problems come back,” says money changer Hajji Asadullah, gripping bundles of U.S. dollar bills, Gulf currencies and tattered local Afghani notes, all wrapped tightly in rubber bands.

Three years from the end of NATO combat missions and a total transfer to local security, Afghan officials are thinking hard about how to stop the flight of hard currency like dollars, euros or scrip from Gulf countries like the United Arab Emirates (UAE) that usually happens when nervousness overtakes their countrymen.

“It is the main topic of conversation now,” says Naseem Akbar, who heads Afghanistan’s Investment Support Agency and whose job is to lure investment, rather than stop it going out. “The worry is about the country going into crisis, and parallel to that is that from now until 2014 we must work out how to avoid such a calamity.”

A U.S. government audit report last year found it was almost impossible to track where much of the billions of dollars spent on security and development projects in the last decade had gone given the country’s dysfunctional financial tracking system and poor bank oversight.

Wealthy Afghans have for years locked their money into safe havens and property elsewhere, with Dubai and its man-made Palm Jumeirah island being favoured locations, with an estimated $8 billion stashed away in the Arab emirate.

But Haji Sher Shah Ahmadzai, the millionaire owner of a group of construction companies in Kabul, said property prices at home jumped by 15 percent at the start of last year after foreigners pledged to support Afghanistan well beyond 2014.

Confidence, however, began leaching away with the September assassination of former president Burhanuddin Rabbani, who headed an Afghan peace council trying to launch talks with the Taliban.

“A flat cost around $220,000 months ago, but now it costs around $140,000 because of the uncertain situation,” Ahmadzai told Reuters in his heavily-guarded office in the upmarket Wazir area of central Kabul.

Afghanistan is perennially among the world’s most corrupt nations listed by Berlin-based anti-graft body Transparency International.

But growth has defied that reputation, averaging around 9 percent in recent years as war and aid spending worth more than $50 billion fuelled a spending boom in Kabul’s dusty streets, now choked with private cars as well as NATO convoys.