The Mahdi wears Armani: The bizarre world of Adnan Oktar

William Armstrong - william.armstrong@hdn.com.tr

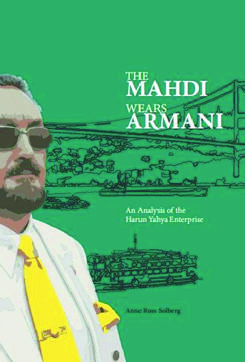

‘The Mahdi Wears Armani: An Analysis of the Harun Yahya Enterprise’ by Anne Ross Solberg (Södertörn University Press, 240 pages, $30)

‘The Mahdi Wears Armani: An Analysis of the Harun Yahya Enterprise’ by Anne Ross Solberg (Södertörn University Press, 240 pages, $30)The movement of Adnan Oktar, aka Harun Yahya, has been described as an “Islamic sex cult supporting Turkey's prime minister” peddling a “sexed-up Disney version of Islam.” Presiding over a network of surgically-enhanced Gucci-clad followers, Oktar is perhaps the world’s foremost Islamic creationist, and is widely ridiculed by social scientists as little more than a “charlatan” or a “crackpot.” Still, his eye-catching brand of Islam has proved a lucrative and tenacious force in Turkey and abroad for almost three decades, and at least one doctoral student has apparently deemed it worthy of deeper academic study. The resulting 250-page book by Anne Ross Solberg, published by Södertörn University in Sweden and also available for free online, ends up being one of the more entertaining doctoral theses that one is likely to come across.

First gaining a following as the leader of a small religious group at an Istanbul university in the 1980s, Oktar sought to attract wealthy and influential Istanbul youths with a materially fulfilling brand of Islam. He made a name for himself penning anti-Semitic, anti-Freemasonry, anti-Communist, conspiracy theory-laden tracts, which culminated in his 1987 opus “Judaism and Freemasonry.” This mammoth 550-page treatise argued that Jews and Freemasons had infiltrated state institutions in Turkey aiming “to erode the spiritual, religious, and moral values of the Turkish people and make them like animals.” It was printed close to 100,000 times, but soon after the book's appearance Oktar was prosecuted in Turkey on charges of promoting a theocratic revolution. He ended up serving 19 months in jail, 10 of which he spent in a mental institute diagnosed with obsessive-compulsive personality disorder and schizophrenia. Nevertheless, after Oktar’s release his group continued to expand, fervently embracing anti-Darwinist creationism and establishing the “Science Research Foundation” (BAV) in 1990. The personality cult surrounding him also ramped up a gear, with many in his closest circle apparently believing that he was the Mahdi: The prophesied redeemer of Islam who will rule before the Day of Judgment and rid the world of evil.

First gaining a following as the leader of a small religious group at an Istanbul university in the 1980s, Oktar sought to attract wealthy and influential Istanbul youths with a materially fulfilling brand of Islam. He made a name for himself penning anti-Semitic, anti-Freemasonry, anti-Communist, conspiracy theory-laden tracts, which culminated in his 1987 opus “Judaism and Freemasonry.” This mammoth 550-page treatise argued that Jews and Freemasons had infiltrated state institutions in Turkey aiming “to erode the spiritual, religious, and moral values of the Turkish people and make them like animals.” It was printed close to 100,000 times, but soon after the book's appearance Oktar was prosecuted in Turkey on charges of promoting a theocratic revolution. He ended up serving 19 months in jail, 10 of which he spent in a mental institute diagnosed with obsessive-compulsive personality disorder and schizophrenia. Nevertheless, after Oktar’s release his group continued to expand, fervently embracing anti-Darwinist creationism and establishing the “Science Research Foundation” (BAV) in 1990. The personality cult surrounding him also ramped up a gear, with many in his closest circle apparently believing that he was the Mahdi: The prophesied redeemer of Islam who will rule before the Day of Judgment and rid the world of evil. Oktar has propagated a dizzying array of extreme and often contradictory positions over the years, and one of Solberg’s central aims is to show how these have been shaped by the dominant currents in both Turkey and the world. For all his contradictions, Oktar has been a loyal proponent of the Turkish-Islamic synthesis promoted by the state authorities after the 1980 coup - appealing variously to popular nationalist, Sunni, Atatürkist, neo-Ottoman and conspiracist impulses in his quest to achieve broader market appeal. As Oktar shifted his focus from a Turkish to an international market in the 2000s, his tone similarly changed. Out went the explicit anti-Semitism, and in came a new “ecumenical” emphasis on religious dialogue. The anti-Darwinist creationism also helped, with Oktar declaring himself an anti-Materialist ally of all devout believers and regularly hosting Jewish and Christian representatives on his personal talk show, broadcast on his private network A9. He has also produced a huge oeuvre of glossy quack-scientific textbooks purporting to debunk evolutionary theory. In 2007, copies of his 6kg, 800-page anti-evolution epic “The Atlas of Creation” were sent unsolicited to the United Nations, the U.S. Congress, and university biology departments around the world. As part of his anti-Darwinist crusade, he even managed to get Richard Dawkins’ official website banned in Turkey through a court order in 2008. Such acts have allowed Oktar to plausibly claim the title of the world’s foremost Islamic creationist.

This shifting emphasis as Oktar went global mirrors the trajectory of another Turkish Islamic religious group, the Fethullah Gülen community. As his own movement expanded, Gülen gradually dropped his trademark fiery Islamic sermons in favor of a softer-edged, dialogue-focused ecumenism. But the comparison only goes so far. The Gülen movement has considerable social and political significance and is supported by broad-based civic and economic foundations, while Adnan Oktar and his close circle of android-like followers remain little more than an oddball curiosity. Although relatively prominent, his enterprise is widely derided as a joke, and it often feels like Solberg’s book is using a sledgehammer to crack a walnut; it’s certainly questionable whether Oktar’s outlandish ideas actually warrant the thoroughgoing examination that Solberg puts them through. It’s also a shame that she doesn’t spend more time on some of the spectacular criminal accusations that have been hurled at Oktar over the years. There are plenty, but the man is notoriously fond of filing defamation cases so I’m not going to go through them here either.

Like much else in the country, the Adnan Oktar/Harun Yahya enterprise combines the outrageous with the deeply disturbing. It can perhaps be seen as a kind of warped lab experiment emerging from the intersection between religion, popular culture, consumer capitalism and marketing technologies in post-1980 Turkey - an eloquent testimony to a place where a surreal turn of events is never far away.