‘You shall not buy’: Syrians and real estate ownership in Turkey

Omar Kadkoy*

In September, 1,276 homes were sold to foreigners in Turkey. Among the top five foreign buyers were three Arab nationalities: Iraqis, Saudis and Kuwaitis. The non-Arabs were the Russians and the British. Together, these five nationalities bought half of the real estate sold to foreigners, according to official data. Similarly, in 2015, Arabs bought 45.9 percent of all real estate sold to foreigners in Turkey, dominating the top three once again. At first glance, all appears to be in order, and Turkey seems to be attracting a satisfactory amount of Arab capital.

In September, 1,276 homes were sold to foreigners in Turkey. Among the top five foreign buyers were three Arab nationalities: Iraqis, Saudis and Kuwaitis. The non-Arabs were the Russians and the British. Together, these five nationalities bought half of the real estate sold to foreigners, according to official data. Similarly, in 2015, Arabs bought 45.9 percent of all real estate sold to foreigners in Turkey, dominating the top three once again. At first glance, all appears to be in order, and Turkey seems to be attracting a satisfactory amount of Arab capital. But why do Syrians have no presence among foreign buyers?

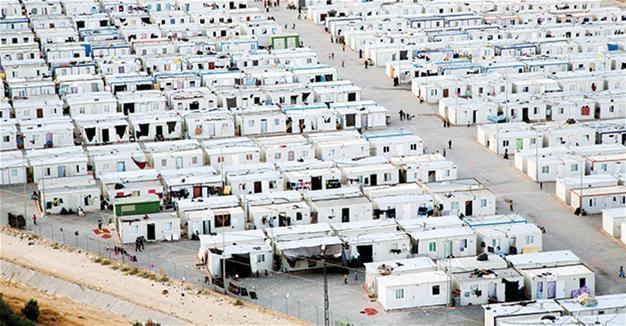

Syrians represent about 3.5 percent of the Turkish population now. More importantly, according to the Directorate General of Migration Management statistics, some 90 percent of Turkey’s Syrians reside outside camps. So even considering the relative poverty of the Syrian refugee population, one would assume that their real estate acquisitions in Turkey would at least show up in numbers. But they do not, due to a legal impediment. Article 35 Clause 2 of Turkey’s Law on Property No. 2644, issued in 1934, references other regulations and notes certain limitations with respect to foreigners acquiring property in the country. One of the referenced regulations single out Syrian nationals and prohibit them from owning real estate in Turkey.

This law has its roots in the 1920s, when Turkey and the region’s borders were being drawn. The Ankara Agreement, signed between France and the Ottoman Empire in 1921 rendered the Sanjak of Alexandretta (today’s Hatay province) autonomous. When Turkey declared its independence in 1923, Syria was already divided into five states under the French Mandate and the Sanjak of Alexandretta was annexed to the State of Aleppo until 1924. Turkey claimed the Sanjak of Alexandretta, present-day Hatay province as part of its territory, leading to a long diplomatic back-and-forth between Turkey and France, and eventually the Arab Republic of Syria, which came about in 1930. In the following years, the Sanjak of Alexandretta first became nominally autonomous, and following a referendum in 1939, was incorporated into Turkey as the province of Hatay.

But the Arab Republic of Syria had never entirely foregone its claim on Hatay. Turkey in turn, felt that Syria might try to stir instability in the then-largely Arabic speaking province. The law banning Syrian land purchases in Turkey was therefore put in place to prevent Syrians from buying back land in Hatay and somehow trying to reassert sovereignty over the province in that way. Since the 1930’s however, the Turkish-Syrian border is well-established, and with such a scenario no longer in question, the law seems redundant.

In May 2012, Turkey relaxed its laws for foreigners’ land acquisition within its borders, largely to allow foreign money to come in, including foreign companies and Turkish companies partially or wholly owned by foreigners. This has brought in much-needed liquidity in the wake of the global financial crisis. The impact of the new policy can be seen in property sales to foreigners, which were at $3 billion in 2013, $4.3 billion in 2014, and $4.1 billion in 2015. For Syrians, however, land acquisition in Turkey has remained complicated, to say the least.

Turkey is increasingly seeing the participation of a new group in its domestic economy. Between 2011 and 2016, there were 3,631 Syrian owned or partnered companies established in Turkey, including 1,600 in 2015. Thanks to the recent amendments to land ownership laws, establishing shell companies has become the way for some well-off Syrians to purchase real estate for personal use.

But how do they do it?

Syrians who want to acquire property in Turkey run into a problem of documentation. Legally speaking, the process of establishing a company – to run a business or as a means to own property – starts with having a lease as a proof of location. As a first step, this lease needs to be notarized for the person to be able to carry on with the rest of the paperwork. For Syrians, a translated copy of their valid passports is required as identification. Given the circumstances that lead to Syrians fleeing their country, many Syrians cross the border into Turkey without passports. Most Syrians in Turkey are given temporary protection identification cards by the Turkish government, and to travel with these even within the country, they need written permission from their local police station. These IDs are not enough to officially own or lease an apartment in Turkey.

“We will grant residency and work permits to those who come from abroad … [and] buy a residence above a certain scale,” said Deputy Prime Minister Mehmet Şimşek in a speech in May 2016.

Well, the 2.7 million Syrians do not really need residence permits to ‘reside’ in Turkey, their legal status is regulated under the Temporary Protection Law. They also have at least some access to the labor force, albeit with significant restrictions, under the foreigner work permit regulation put into force in January 2016.

Furthermore, even though the legal framework is in need of a comprehensive overhaul, Syrians also have free access to public health and education services in Turkey. But still, this doesn’t change the fact that a now-obsolete law of the early Republic era blocks nearly 3 million residents of the country from buying real estate.

If the Turkish government is still determined to design and implement a sustainable integration framework for its not-so-temporary Syrian population, removing this outdated legal block would be a good step to indicate their will.

* Omar Kadkoy is a research associate at TEPAV.