Walk of the lambs

AYLİN ÖNEY TAN - aylinoneytan@yahoo.com

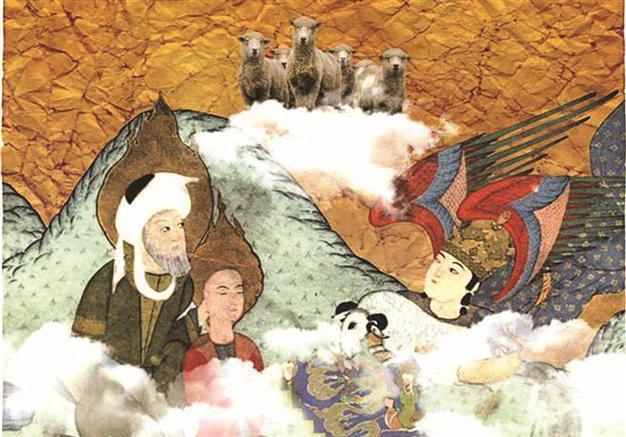

Another carnivorous “Feast of Sacrifice” has just passed, leaving blood-red stains in our urban landscapes. Known as “Kurban Bayramı” in Turkey and Eid al-Adha for the rest of the Muslim world, it is one of the two most important holidays of the Islamic year. As its name suggests, it is celebrated by sacrificing an animal. The holiday commemorates the dramatic story of the Prophet Abraham and his son Ishmael, an early Islamic narrative common to Judaism and Christianity as well. According to the story, the prophet’s trial to prove his commitment to God by sacrificing his first and only son had a happy ending as an angel intervened at the last moment to replace the son with a lamb. The son was saved, but the lambs were doomed forever.

Another carnivorous “Feast of Sacrifice” has just passed, leaving blood-red stains in our urban landscapes. Known as “Kurban Bayramı” in Turkey and Eid al-Adha for the rest of the Muslim world, it is one of the two most important holidays of the Islamic year. As its name suggests, it is celebrated by sacrificing an animal. The holiday commemorates the dramatic story of the Prophet Abraham and his son Ishmael, an early Islamic narrative common to Judaism and Christianity as well. According to the story, the prophet’s trial to prove his commitment to God by sacrificing his first and only son had a happy ending as an angel intervened at the last moment to replace the son with a lamb. The son was saved, but the lambs were doomed forever.One of the pillars of Islam is to do the pilgrimage to Mecca, and the pilgrim is expected to sacrifice an animal upon completing the pious voyage. However, not everyone could make this pilgrimage, so people in the past used to make their sacrifice in their hometowns. It was always the choice of meat that determined the selection of the sacrificial animal. In Arab countries camels could be the ultimate sacrifice but for Ottomans, sheep have been always the favorite. However, it was not that simple, leading to the question: which lamb?

Istanbul was a huge metropolis even by the standards of the olden times. By the 19th century, the city had more than a million inhabitants. Feeding the city was made possible through a set of strategic organizations. The Feast of Sacrifice meant a huge demand for livestock, way more than the city could host. Most of the meat supply of the city had to be practically walked in to the metropolis from faraway lands. It was a moveable feast, with poor sheep slowly walking to their death.

The Ottoman government was very organized in this business, regulating the transfer of the flocks, and also paying for the expenses to provide the poor with sacrificial lambs. The chief butcher, “kasapbaşı,” was responsible for over-seeing the whole activity. There were several locations around Istanbul, close enough to move a feast on foot, but apparently some flocks came from very faraway lands, as one document reveals.

According to an article titled “İstanbul’s Moveable Feast” by Chris Gratien of Georgetown University, almost two centuries ago there had been a massive “pilgrimage” of livestock to the Ottoman capital. The author gives a detailed account of this dramatic exodus of the soon-to-be-dead sheep from all over the empire.

“In 1817, Eid al-Adha occurred during mid-October, just as it does this year. As this document and accompanying map show, the fall feast would require mustering 165,300 animals from Europe and Anatolia. Almost 100,000 male sheep from the Eastern European regions of the empire such as Wallachia (Eflak) and Bulgaria and another 70,000 from Anatolia of the Kıvırcık and Karaman breeds would supply the capital with sacrificial animals. According to the document, all of these animals were males (erkek ağnam). The kasapbaşı reports that the animals were present and ready in the capital by 5 Zilhicce, a few days before the upcoming feast,” Gratien writes.

As seen from this document, timing was astonishingly precise. As the Feast of Sacrifice starts at the month of 10th Zilhicce of the lunar calendar, five days prior to the feast was just right to give the poor animals a final break before their final departure!

Well, we all expect an angel intervening with our fate at the last moment, leading us to a happy ending, but for the poor marathon-walking sheep herds of Ottoman times, the angels never appeared, maybe because the transfer of such an immense flock of good-willed angels to earth was too complicated.

For the entire post on the walking feast go to the link:

http://www.docblog.ottomanhistorypodcast.com/2013/10/sheep-sacrifice-bayram-ottoman-empire-istanbul.html

Bite of the week

Recipe of the Week: I suggest a typical celebration dish of Anatolia, keşkek, normally a wheat-berry stew with meat, but this time veggie with mushrooms: “Mantarlı Keşkek.” Pick over and wash ½ kg whole wheat-berries. Place in a pot with water double the volume of wheat. Add 1.5 teaspoons of salt and cook until the wheat is plumb and tender. Clean and slice a ½ kg mushrooms. Choose chestnut mushrooms, or a mixture of many, but try to include a few fresh or dried porcinis. In a deep pan, sauté one big, finely chopped onion and 2 cloves of mashed garlic in 3-4 tablespoons butter. Add the sliced mushrooms. Add a mixture of ½ teaspoon each of freshly ground black pepper, allspice, cinnamon, coriander and a sprinkle each of clove and nutmeg. Stir-fry until all the cooking juices of the mushrooms disappear. Mix the mushroom into the cooked wheat-porridge. Cook for a further half hour for the flavors to mingle. It will have the appearance and consistency of a risotto. Adjust the flavors and serve with drizzle of fruity early harvest olive oil and more black pepper.

Fork of the Week: It’s OK to go for the meat, too. Why not try a burger on the meaty side, but please skip the chains and go for the dedicated burger joints. Two places in Karaköy stand out: Burgerlab and Baltazar; the former focuses on their own burger creations; the latter has also smoked meat and homemade sausage. Students favor Biber Burger in Beşiktaş, just opposite to Bahçeşehir University. Virgina Angus is off the beaten track or more in the tourist path, on Mercan Uzunçarşı Street in Eminönü.Cork of the Week: A carnivorous feast needs a hearty red wine, and the same is true for forest mushrooms. So whether your feast is a meaty or veggie one, you need a good bottle to go with. My pick has recently received 91 points from Wine Enthusiast 2014. Suvla Grand Reserve Cabernet Sauvignon 2011 is produced exclusively from Cabernet Sauvignon grapes grown on a single parcel of the Suvla family vineyard, Bozokbağ, on the Gallipoli Peninsula. Matured in oak barrels for 12 months, the tasting note says it has a bouquet of blueberry, mocha, cigar box and leather, leading to a long finish.