Tragedies of children in Turkish cinema revisited

Emrah GÜLER

Ömer Can’s debut 'Toprağa uzanan eller' (King of the cotton) tackles one of Turkey’s endemic problems, child labor mixing magical fairy tales with the everyday reality. ‘Toprak’ not only means soil, but is also the name of the movie’s little hero.

It’s hard not to feel a sense of déjà vu that you are being taken to the Turkish cinema of the 1950s upon reading the press release for last week’s release “Toprağa Uzanan Eller” (King of the Cotton), the debut feature of Ömer Can. The synopsis reveals that the protagonist is the eight-year-old Toprak who is cut off from his childhood, heading to the cotton fields as a seasonal worker.Toprak’s older sister is married off to a much older man for a good amount of dowry. And to top the series of tragedies the siblings have to live through, their little sister Zeliha has become blind after suffering poliomyelitis. Children suffering onscreen was a familiar picture in 1950s’ Turkish cinema. Children and their misfortunes were the ultimate source of melodrama, bordering emotional exploitation.

The tragedies children had to face onscreen were always too large for their short lives. Most of them were abandoned by their parents, often born out of wedlock to ultimate shunning, left on the streets to fend for their own. Some of the titles will give you an idea, “Bırakılan Çocuk” (The Abandoned Child), “Evlat Acısı” (Loss of a Child), “Yetim Yavrular” (Orphan Babies), “Evlat Hasreti” (Missing the Child) and “Bir Yavrunun Gözyaşları” (Tears of a Baby). Not to be misled, some of the movies of the period with children in their titles didn’t feature any children.

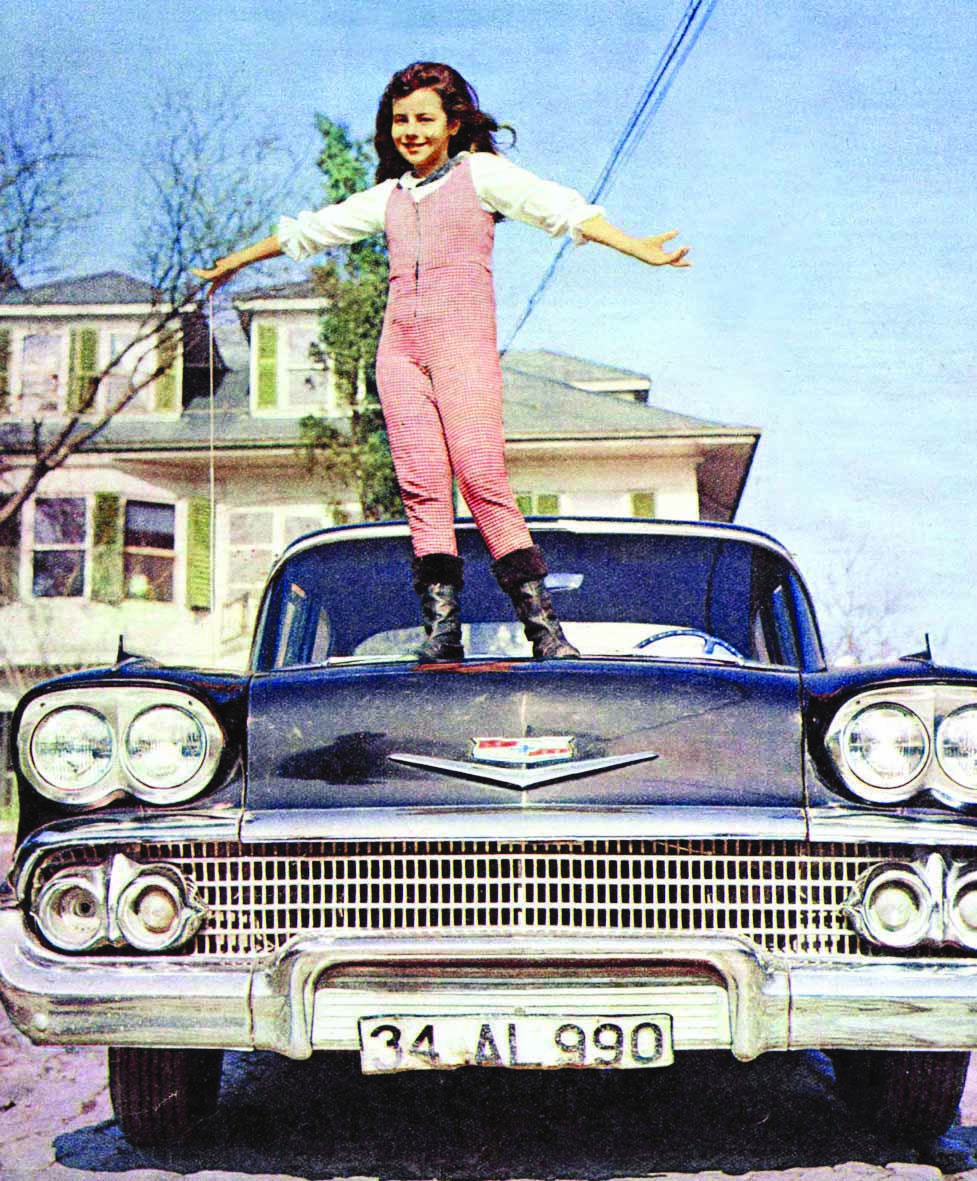

The golden age of child stars in Turkish cinema came in 1960s, more like the golden age of a specific child star. Zeynep Değirmencioğlu was Turkey’s answer to Shirley Temple. From the age six until she was a teenager, Değirmencioğlu played the same character, Ayşecik (Little Ayşe, on the left). The exploits of this little girl became a pop culture phenomenon instantly, keeping Turkish cinema running for about a decade. She might have lived in the big city or in a village, an orphan or a happy child, no matter, the character was always Ayşecik.

The golden age of child stars in Turkish cinema came in 1960s, more like the golden age of a specific child star. Zeynep Değirmencioğlu was Turkey’s answer to Shirley Temple. From the age six until she was a teenager, Değirmencioğlu played the same character, Ayşecik (Little Ayşe, on the left). The exploits of this little girl became a pop culture phenomenon instantly, keeping Turkish cinema running for about a decade. She might have lived in the big city or in a village, an orphan or a happy child, no matter, the character was always Ayşecik.Ayşecik mostly came from a poor family living in the big city, and she always was far mature beyond her years. She was the mediator, problem solver, crisis manager and sometimes even the breadwinner. She made sure that her parents overcame their problems and patched things up, went to work if her family was in a dire strait, and looked after her brother as only a mother could. When you listened to Ayşecik, you saw a wise woman beyond her years and age.

From exploitation to realistic stories

As Değirmencioğlu (hence Ayşecik) reached her teen years in 1970s, the film studios wanted to continue with this tried and tested formula, but with fresh faces. Değirmencioğlu’s real-life cousin Ömer Dönmez came to the rescue, becoming the little boy Ömercik, a wise man beyond his years and age. Unlike his cousin, he didn’t dominate the screen, sharing time with other little philosophers and do-gooders, adults trapped in little children’s bodies.

The 1970s was the period when producers, directors and actors put their children’s young acting prospects into leading roles. Yumurcak (The Little Menace), Afacan (Little Rascal), Sezercik (Little Sezer) and Gülşah were all offspring of popular directors, producers and actors of the time. As Turkish cinema opened its heart to another form of exploitation in the form of pornography for the big screen, children as a source of unabashed exploitation thankfully left the Turkish cinema.

'King of the Cotton' follows Toprak reciting his days in the cotton

fields to his sister, only taking out the true hardships and replacing

them with fairy tale.

Child actors and child characters never actually left Turkish cinema, but they now turned into professionals in realistic roles. Some examples are Tunç Başaran’s “Uçurtmayı Vurmasınlar” (Don’t Let Them Shoot the Kite) of 1989, a child’s accounts of life in prison; Çağan Irmak’s 2005 tearjerker “Babam ve Oğlum” (My Father and My Son), the account of the coup through the eyes of different generations of men; and Reha Erdem’s “Beş Vakit” (Five Times A Day) of 2006, a look at life in its slowest in a village through the lives of children.

Despite its ill-advised press release, “King of the Cotton” falls more into the latter category with impressive acting and full-blown characters. The story follows Toprak reciting his days in the cotton fields to his sister, only taking out the true hardships and replacing them with a fairy tale, where there are princes and princesses. Despite his instinct to protect his little sister, Toprak being a child himself, he soon becomes immersed in his own fairy tale. The film is one of the better examples of narration by children, a fine story through the eyes of children.