The fountains of Ottoman Istanbul

NIKI GAMM

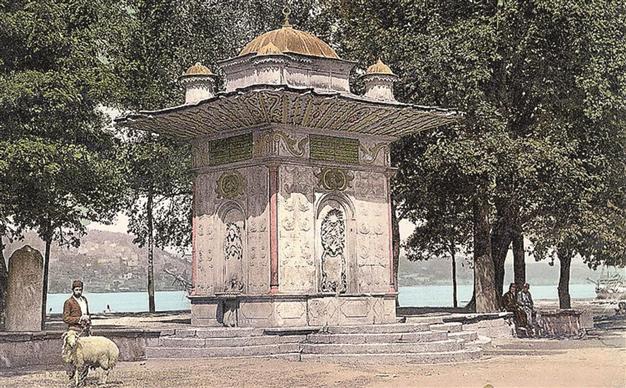

Küçüksu (Mihrimah Valide Sultan) Square Fountain, beginning of the 20th century.

You could find them on walls or in plazas, as part of mosques and freestanding, at corners, in rooms and even as cabbage-headed columns. These were the forms of fountains that adorned Istanbul in the Ottoman period and they can still be found today if you know where to look.Over the centuries Istanbul met the water needs of its citizens by building aqueducts from distant sources, for its time as the capital of the Eastern Roman Empire in the 4th century. With repairs and rebuilding the water system, the Byzantines kept the water flowing but by 1453, when the Ottoman Turks conquered the city, it needed a complete overhaul. The addition of new water sources had to wait until the reign of Sultan Süleyman the Magnificent (r. 1520-1566) in the next century.

One has to assume that the Byzantines had fountains because the Romans did, but today no trace of these remains. Instead we have many fountains from the Ottoman period the were common until pipes bringing water directly into individual houses were laid in the 19th century. An important difference between the Ottomans and those who went before was that the former expected, (and where ritual purification was concerned required), that water be flowing: The hamam vs. the bath. The answer was to build fountains throughout the city, an idea probably taken from the Persians and the Seljuks as the nomadic Ottoman Turks passed through Iran and today’s Syria on the way to Anatolia.

Fountains as charitable works

Fountains as charitable worksCharity in the Islamic world is mandated by religion. It is obligatory to contribute a portion of one’s wealth every year to help the poor and needy. Among the charitable works that were commended was the construction of fountains. The sultans, their immediate family and the paşas (the highest government officials) might build mosques, schools and hospitals, while lower level officials and men of wealth turned to fountains.

The story of the Saliha Sultan Fountain at Azapkapı tells a rags-to-riches story of how one day the Sultan Valide (Queen Mother), Rabiye Gülnüş, was passing by. She saw a little girl, crying, next to a broken jug. Stopping, she offered the little girl money which she refused. She goes home with the girl, talks to her mother and then takes the girl into the imperial harem. Saliha then becomes the wife of Sultan Mustafa II and mother of Mahmud I and, not forgetting her neighborhood, she has another, better fountain built there in 1732.

Many of the very showy Ottoman fountains were built in the Lale Devri (Tulip Period) between 1718 and 1730. The empire was at peace during most of these years and the court under Sultan Ahmed III gave itself over to building palaces and mansions, especially at the fabled “Sadabad” on the north shore of the Golden Horn. There were festivities and celebrations, music, poetry recitations, dancing and other kinds of revelry. The celebrated poet Nedim, who had a fondness for Sadabad, often used the imagery of the fountain in his poems.

“Let us give a little comfort to this heart that’s wearied so

Let us visit Sadabad, my swaying Cypress, let us go!

Look, there is a swift caique all ready at the pier below,

Let us visit Sadabad, my swaying Cypress, let us go!

“There to taste the joys of living, as we laugh and play about,

From the new-built fountain drink a draught such as Tesnim* pours out,

Then to watch enchanted waters flowing from the gargoyle spout,

Let us visit Sadabad, my swaying Cypress, let us go!”

[*A river in Paradise. From The Penguin Book of Turkish Verse]

This was also a time when some of the largest fountains in Istanbul were built, in particular, the fountain in front of the main gates to Topkapı Palace Museum. Sultan Ahmed III had built in 1728 and it stands today on the site of a previous Byzantine fountain as one of the finest examples of the Lale Devri style. Square in plan, it has a fountain on each side and a sebil (a grated fountain from which water would be freely distributed). Inside there is an octagonal water tank. Carved niches and stalactite-like decoration give depth to the walls of the fountain which has a door on one side. The sloping roof has been covered in lead and on top of that there is a dome. The inscriptions above are a 14-stanza poem in praise of water and the donor of the fountain, Sultan Ahmed III, for which the calligraphy was designed by the sultan. He also wrote a chronogram which gives us the date of 1728.

This was also a time when some of the largest fountains in Istanbul were built, in particular, the fountain in front of the main gates to Topkapı Palace Museum. Sultan Ahmed III had built in 1728 and it stands today on the site of a previous Byzantine fountain as one of the finest examples of the Lale Devri style. Square in plan, it has a fountain on each side and a sebil (a grated fountain from which water would be freely distributed). Inside there is an octagonal water tank. Carved niches and stalactite-like decoration give depth to the walls of the fountain which has a door on one side. The sloping roof has been covered in lead and on top of that there is a dome. The inscriptions above are a 14-stanza poem in praise of water and the donor of the fountain, Sultan Ahmed III, for which the calligraphy was designed by the sultan. He also wrote a chronogram which gives us the date of 1728. Gül Sarıdikmen in “Istanbul’un 100 Çeşmesi ve Sebili” (“Istanbul’s 100 Fountains,” published by the Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality’s Kültür A.Ş.) describes it as representing the first structure of Baroque architecture in Istanbul. The poet Nedim even composed a special poem for the fountain, in which he portrays Sultan Ahmed’s exalted fountain as the water of life - flattery was an important means of advancement in Ottoman life.

Fountains as social centers

Until the 19th century, only the palaces and houses of the wealthy could get water flowing to them. The rest of the population could draw on water from the neighborhood fountain. As well, water could be delivered by horse or by porter directly to the door. This water would be gotten from the fountains in the town squares for the most part with some of these being set aside for horses to drink while the others were only for the porters to use. The water would be placed in leather containers for delivery.

At first the fountains were set up so that the water was free flowing but in the reign of Sultan Süleyman taps were introduced when he had Mimar Sinan revamp the entire water system. This not only saved water but prevented the streets from becoming muddy.

Many of the fountains provided seats on which to wait one’s turn in filling jugs. It provided an excellent opportunity for the local people and especially the women to learn the latest gossip and as the water was free, they were saved from having to pay for a visit to the hamam or, in the case of men, to the local coffeehouse.

So the water pipes were laid and the system modernized as Istanbul attempted to westernize in the 19th century and in the words of Mehmed Akif who wrote the word’s to Turkey’s national anthem:

“The channels are gone

The bridges ruined.

The sebils have dried up and

The fountains are shut.”

Some of the fountains are still with us, others have been destroyed or repaired so badly one could wish they had been destroyed. The cabbage-headed fountain? It still stands in Beykoz Paşabahçe, a symbol of the popular, imperial sports team the Cabbages (Lahanacılar) that regularly faced off with the Okras (Bamyacılar) to the amusement of palace.