S Africa bans Sudan president from leaving over arrest warrant

JOHANNESBURG - Agence France-Presse

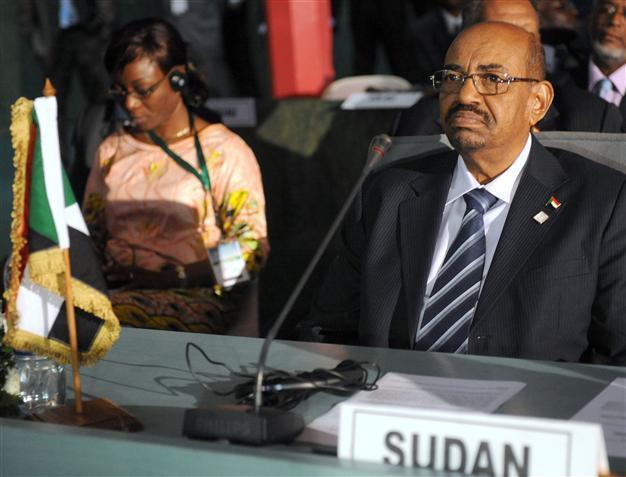

A file photo taken on on July 15, 2013 shows Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir attending the opening session of the African Union Summit on health focusing on HIV/AIDS, TB and malaria in Abuja. AFP Photo

A South African court issued a temporary ban on Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir leaving the country on June 14 after the International Criminal Court called for him to be arrested at a summit in Johannesburg.Bashir, who is wanted over alleged war crimes, crimes against humanity and genocide in the Darfur conflict, mostly travels to countries that have not joined the ICC, but South Africa is a signatory of the court’s statutes.

The Pretoria High Court said in a statement it was “compelling respondents to prevent President Omar Al-Bashir from the leaving the country until an order is made in this court”.

The hearing is set to take place later on June 14, the opening day of the African Union summit.

The ruling came after the Southern African Litigation Centre, a legal rights group, launched an urgent court application to force the authorities to arrest Bashir.

Bashir joined a group photograph of leaders at the summit despite the calls for his arrest.

Wearing a blue suit, he stood in the front row for the photograph along with South African host President Jacob Zuma and Zimbabwe’s President Robert Mugabe, who is the chair of the 54-member group.

Mugabe has previously urged African leaders to pull out of the ICC, which critics accuse of targeting Africa.

The ICC said in a statement from its headquarters in The Hague that it “calls on South Africa... to spare no effort in ensuring the execution of the arrest warrants” against Bashir.

It said South Africa diplomats had been pressed last month to arrest Bashir if he attended the summit, but that they replied they faced “competing obligations” over the issue.

Bashir, 71, seized power in Sudan in an Islamist-backed coup in 1989.

“South Africa has an obligation to arrest him,” Johannesburg-based rights lawyer Gabriel Shumba told AFP.

“Failure to do so puts them in the same bracket as other African regimes who have no respect for human rights. It’s actually a test for South Africa.”

Darfur erupted into conflict in 2003 when insurgents mounted a campaign against Bashir’s government, complaining their region was politically and economically marginalized.

More than 300,000 people have been killed in the conflict and fighting has forced some 2.5 million people to flee their homes, the United Nations says.

Khartoum, however, disputes the figures, estimating the death toll at no more than 10,000.

“Allowing President al-Bashir into South Africa without arresting him would be a major stain on South Africa’s reputation for promoting justice for grave crimes,” said Elise Keppler of Human Rights Watch.

“South Africa’s legal obligations as an ICC member mean cooperating in al-Bashir’s arrest, not in his travel plans.” The two days of discussions among the member states had been set to focus on the political unrest in Burundi and the migration crisis across the continent.

Burundi has been plunged into instability by President Pierre Nkurunziza’s push to run for a third five-year term.

Violent protests have left some 40 people dead and 100,000 people have fled the country, raising peace and security concerns in the region.