Priceless feminist archive goes digital

ISTANBUL – Anadolu Agency

It is a quiet afternoon in Turkey’s only women’s library and Professor Fatmagül Berktay, a renowned feminist academic and activist, is, as usual, hunched over a pile of books.

It is a quiet afternoon in Turkey’s only women’s library and Professor Fatmagül Berktay, a renowned feminist academic and activist, is, as usual, hunched over a pile of books. However, she is not grading papers or doing research; she is signing books from her personal archive to donate to this unique and venerable institution, while also drafting plans to fully digitalize the center’s archive.

Berktay, a professor of political science at Istanbul University and the writer of many books on women’s issues in Turkey, is chair of the executive board of Kadın Eserleri Kütüphanesi ve Bilgi Merkezi Vakfı (Women’s Library and Information Center Foundation).

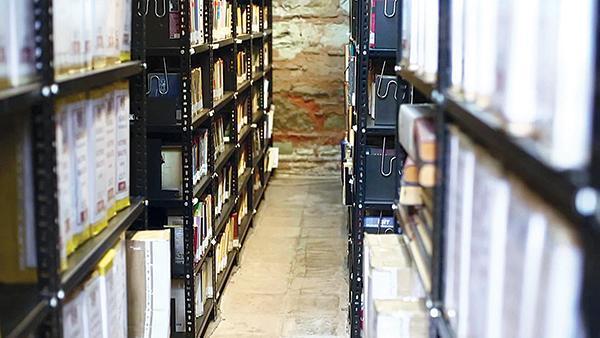

Berktay, a professor of political science at Istanbul University and the writer of many books on women’s issues in Turkey, is chair of the executive board of Kadın Eserleri Kütüphanesi ve Bilgi Merkezi Vakfı (Women’s Library and Information Center Foundation). A renovated Byzantine-era building closely linked to the Fener district’s Greek community, the library was once a female school connected to a nearby monastery on the banks of Istanbul’s Golden Horn.

After going into decline, the building is now home to this special library founded in 1990 by five Turkish women.

The group, who came from academia, librarianship and anthropology, were Şirin Tekeli, Aslı Davraz, Füsun Akatlı, Füsun Ertuğ and Jale Baysal.

Having prevailed against the odds, Turkey’s largest women’s archive and library is now looking for new ways to expand and fund itself after a 2015 campaign where donors could contribute a modest 25 Turkish Liras.

“We remain standing [only] with donations,” Berktay said in the meeting hall of the library’s second floor where, despite a pleasant and quiet atmosphere, old and out-of-date PCs are still used to keep records.

The room’s walls are decorated with paintings and sculptures donated by Turkish feminist artists.

Some other objects in the hall are a typewriter that belonged to Kerime Nadir, Turkey’s best-selling female writer, who published more than 40 blockbusting books, plus a painting by Mihri Müşfik Hanım, one of the first and most-renowned Turkish female artists.

The library, which forms an important part of Turkey’s women’s memory with its unique archive, hosts more than 12,000 books, over 400 magazines and 10,000 periodicals, as well as more than 5,000 articles plus 526 post-graduate and doctoral theses.

The oldest piece at the library is a Greek-language women’s magazine called Kypsela that dates back to 1943, Berktay said.

According to Berktay, the library’s creation was sparked by a women’s movement which developed during 1980s Turkey when a military coup overthrew the elected government.

“We were all part of this movement,” she said. “Through the 1980s the women’s movement, we discovered both our ties with the Ottoman women’s movement and the rising second wave of feminism around the world.”

This modern women’s movement forced Turkish society to confront uncomfortable issues, such as violence against women, Berktay said.

“All those things [opening of the library and foundation of a women’s ministry in Turkey’s government] were not just coincidences; the women’s movement in the world and in Turkey were behind it,” she said.

This groundbreaking work is supported by the small Fener library. Around 190 people’s small contributions helped the library get started; Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality later donated the historic building.

For Berktay, the importance of the library’s collection is to create a “women’s memory” in Turkey.

“Women and men are the ones who create history but because history is not written by women, they are not mentioned. A special effort is needed to reveal women’s history,” she said.

“The library documents not only the fight of the Turkish women’s movement but also women’s struggle to become individuals in the country and build a bridge between the past and the future,” she said.

Berktay said women living in the Ottoman Empire during the 1910s would “openly call themselves feminists.”

“They were saying ‘feminism is a highly respected movement and men and women who have reached maturity should become feminist,’” Berktay said.

In 1913 women demanded their voting rights, she said. “They wanted to watch parliamentary meetings and were dreaming about having voting rights one day. They were saying ‘If you do not give us our voting rights, we will chain ourselves like British suffragettes in front of the parliament building.’”

“Suffragette” is a term used to describe members of a women’s organization, mainly in the United Kingdom, which fought for women’s right to vote in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

“It is so obvious that [Ottoman-era feminists] were in contact” with like-minded women around the world, she said.

Berktay said that when the 100th anniversary of the Battle of Gallipoli occurred last year, the commemoration was of modern Turkey’s foundation.

“Nobody mentioned women,” during the celebrations, she said, giving an example of a nurse called Safiye Hüseyin Elbi, who worked for the Ottoman army in Çanakkale, where much of the fighting took place.

The library now has both Elbi’s school diploma and her passport for posterity.

For Berktay, another very important job the library has done so far is to translate Ottoman-language women’s magazines into modern Turkish.