Peace on a gravestone: A glimpse into Kurdish grievances at Istanbul Film Festival

Özgün Özçer

‘Endless Grief’ takes us into Selim's journey to document the recent history, capturing witness accounts and testimonies, which his his way of striving against the loss of his son in the mountains.

I first met Selim five years ago. Just like everybody else, I could not help admiring his positive energy, warmth and innate kindness. The camera, which seemed to be permanently attached to his hands, encapsulated his resolution to make the most of every moment of life.But underneath his unfading smile lies a tragic story… a hardly exceptional one for any Kurd, but a story hushed up and altered for those who grew up in another territory.

Selim lost his son, Ozan, in the “mountains,” a euphemism for joining the armed fight of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK). Despite having recently started a sociology degree at Ankara’s prestigious Hacettepe University, Ozan disappeared on a spring day in 1999 without any previous indication that he might one day take up arms.

That started a five-year frantic and uncertain search for Selim, during which he tracked every piece of information about Ozan’s life like an intelligence officer. On another spring day, he received the first call from his son in five years. Ozan arranged an impromptu appointment with his father, requesting a bunch of books, a Walkman and a camera. He died only a week after that conversation between father and would-be prodigal son, reportedly during combat.

Selim now tracks bones and yearns for a gravestone – “kêl” in Kurdish – to find closure. That camera, the one that never leaves his hands, is his companion to document the mass graves that are the final resting place of hundreds who died like his son. That camera, the one he carries as if it were attached close to his heart, is in fact a tribute to Ozan’s biggest passion, a way of striving against his loss in the absence of a gravestone…

Stones of justice

Turkey’s recent history is plagued by those untold stories haunting mothers who have nowhere to mourn their children, sons who are trying to retrace their father’s death, wives who are still waiting for their husbands’ return, with a hope that is dim, yet still alive.

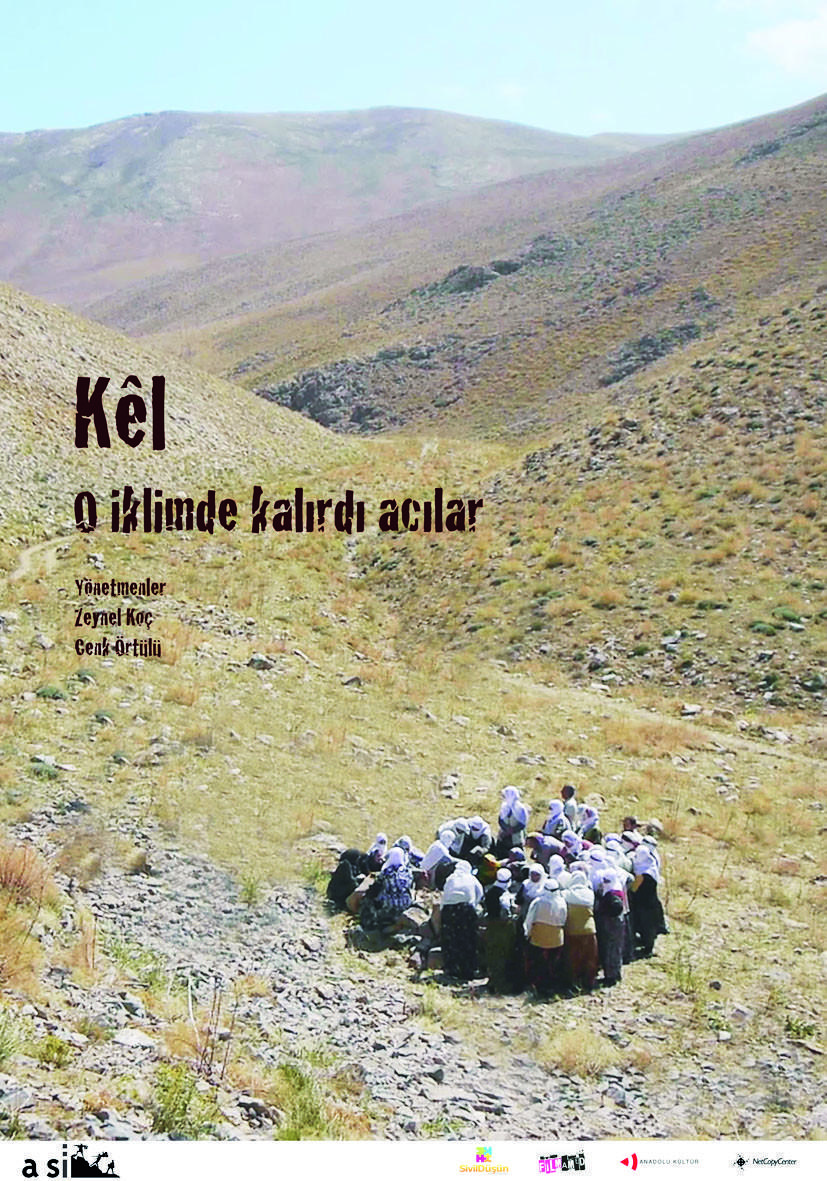

The documentary “Endless Grief” (O İklimde Kalırdı Acılar – Kêl) by Zeynel Koç and Cenk Örtülü, screened as part of the Istanbul Film Festival, is one of the most comprehensive and bravest attempts to confront that recent past. Within a brief hour, it makes the audience grasp that the past cannot be left behind in a true sense without solving the problem of what Kurds commonly term “gravelessness.” Over 200 mass graves have been documented and forensic work has been conducted on many of them to identify the victims, but hundreds are still waiting to be opened.

Together with his camera, Selim guides us in his journey to capture witness accounts, testimonies and what remains of the lost, may it be a piece of cloth or bullet shells. Throughout the documentary, we quickly discover that his search for inner peace intersects with societal peace and that this is a climate where even the most intimate emotions are inseparable from politics.

There we meet Adnan, on the outskirts of Diyarbakır’s town of Lice, a district always prone to tension. He is beyond resentment when he relates how his father was set up. Adnan says that his only regret is not having been able to bury him, “to perform his last offices,” as he puts it. Or Mother Şerife, who tries to translate into words how much pain and suffering she endures following the loss of two of her sons.

There we meet Adnan, on the outskirts of Diyarbakır’s town of Lice, a district always prone to tension. He is beyond resentment when he relates how his father was set up. Adnan says that his only regret is not having been able to bury him, “to perform his last offices,” as he puts it. Or Mother Şerife, who tries to translate into words how much pain and suffering she endures following the loss of two of her sons.The most humbling message subtly raised by all these testimonies is that it is not sufficient to pledge peace and change without a firm methodology for achieving it – in other words, without ensuring justice. This goes from hearing the demands for apologies to properly opening the mass graves, in line with international procedures. For instance, instead of exacting the maximum care to retrieve the remains of the victims, authorities have dug them with bulldozers. The acts not only further alienated Kurds, causing more indignation, but were also a blatant breach of the Minnesota Protocol, which was created by an international group of forensic specialists and lawyers to provide detailed procedures for conducting autopsies.

Although it is not openly stated, the necessity for a truth and reconciliation process that could establish the circumstances of the deaths underlie the patchwork of testimonies crafted by the documentary. Questions remain unsolved over who was forcedly disappeared, who was executed and who died in actual fighting; questions that will always remain as a barrier between a much-desired societal peace and the inner peace of each person.

Peace requires empathy, communication and goodwill. But its echo rings hollow when people are still searching for the remains of their loved ones. As Selim says in one poem dedicated to Ozan:

Every night in my dreams, I see a gravestone

A chalk-white stone, without any inscription

Every time I go to the cemetery, my eyes search for that stone, in vain…

And what may be just a stone for you

Is my past, my hope, my blood and my milk

“Kêl” gives a compelling account that without closure, there is no sincere reconciliation. And only then may Selim, Adnan, Şerife, Türkan and all the other unnamed families be able to rest, in peace.