Ottoman autumn – a preparation for winter

Niki Gamm

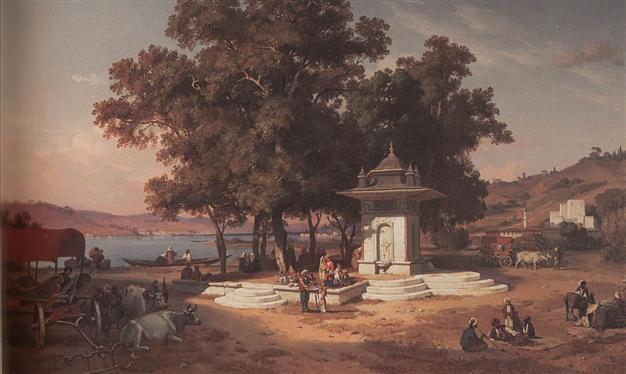

Küçüksu Fountain as Autumn begins, Max Schmidt.

"There’s no trace of spring leftThe tree leaf has fallen on the grass

The orchard trees wear the robe of divestiture

The autumn wind in the grass has the plane tree’s permission.

Golden is the flow at their feet from every side

The orchard trees hope for the river’s favor.

Don’t wait on the grass’ theatrical stage. Let it sway with the light breeze

The sapling is free of leaf and fruit.

Baki, the leaf is distraught in the grass

It resembles a complaint against the wind."

The 16th century poet, Baki, is considered one of the greatest of the Ottoman poets. His “Ode to Autumn,” translated above, hardly represents the original language, but still conveys the idea. There are many more Ottoman poems lauding spring than autumn and if you’ve spent any part of the winter in Istanbul where most Ottoman poets lived, you’d think you understood why. In fact Istanbul didn’t have “summer.” The Ottomans had spring (bahar) and late spring (sonbahar). Even the Turkish word for summer (yaz) meant spring in Ottoman times.

Returning to base

Bebek Mosque, Sami Yetik.

But once the autumn equinox passed (Sept. 21-22), it became time to prepare for winter which was just as unpredictable then as now. Think of a winter when the Bosphorus and the Golden Horn froze over. One of the first indications would be the decision for the Ottoman army to return to winter headquarters since it took time to bring tens of thousands of men back to Istanbul regardless of whether they had been fighting in the Balkans or on the eastern front. One exception was the army under Yavuz Sultan Selim I (r. 1512-1520) which was fighting in the southeast Anatolia-Syria area. If he hadn’t decided to bivouac there, it’s unlikely that he would have been able to go on the following year (1517) to conquer Egypt and take over control of Mecca and Medina.

The Ottomans who had spent a delightful “spring” in their yalıs (waterside mansions) would begin considering their own return to the center of the city. A rather forlorn Dorina Neave writes in her memoirs, “Twenty Years on the Bosphorus,”

“Most of our friends migrated to Constantinople for the winter season, but we remained at Candilli … I honestly hated those long dreary winters spent on the Bosporus, when the beautiful summer weather had broken up and we were faced with the depressing prospect of cold, wind-swept, and stormy winter months. How I envied our friends, comfortably settled in the sheltered town of Pera, where gay society foregathered for the winter! The exodus began in October, when the summer residences, unprovided [sp.] with central heating, or even with stoves with their hideous black pipes that were used in every room in town, became untenable at the approach of the north-wind storms, heralding autumn’s cold spell and the end of the Bosphorus season.

“A continual stream of bazaar caiques laden with furniture passed by our house, rowed by crews of ten or twenty caiquejis, on their way to Constantinople, where hamals awaited their arrivals…

“It was the last sign of summer when the embassy stationnaires finally steamed past from Therapia and Buyukdere, to take up their winter anchorage at Tophane…”

Karacaahmet Cemetery, Nazmi Ziya Güran.

Sakıp Sabancı Collection

Today we can rely on finding almost every kind of foodstuff all year round but that wasn’t the case in Ottoman times. Many basic items were kept in households depending on the financial level of the family. A normal Ottoman kitchen would have rice, wheat flour, starch (or wheat paste used for thickening), ırmık (semolina), sugar or honey and clarified butter. Spices would include salts of various kinds, black pepper, cinnamon, cumin and mint. There would be plenty of dried vegetables and fruits such as lentils, chickpeas, beans of various sorts, okra, grapes, apricots, figs and cornelian cherries. The fruits would be made into jams. Rosewater and orange petal water were used in many recipes as was lemon juice, vinegar, tomato sauce, hazelnuts, walnuts, chestnuts, onion, garlic and tarhana (a soup made of dried curds and flour).

Although it was impossible to keep fresh meat around without refrigeration, pastırma and sücük would be made in autumn. Vegetables and fruits would be pickled – all of the Fall vegetables like cabbage, carrots, celery, spinach and leeks as well as some fruits such as melons, watermelons, apples, grapes and even fish. Some salted and/or dried fish and meat were supplemented with sausage.

Autumn was also a time to collect wild plants that were used as medicine. Alıç (the Neapolitan Medlar) for instance is a small tree whose flowers and fruit were used by Ottoman soldiers as a medicine for muscle building when going on campaign. It was also considered good for the heart, diabetes and blood pressure. This was only one plant of many that would be gathered in the autumn.

Sabun would be prepared in autumn to last through the winter. Carpets, kilims and thick bed coverings of wool would be brought out for airing and cleaning, if necessary. Woolen stockings would be knit and warm woolen under and over garments sewn since there was nothing like today’s ready-to-wear. Only the wealthy, high level government officials and members of the imperial family were allowed to wear fur.

The household would get in wood before it rained, storing it in a depot or in a small woodshed. Coal wasn’t used until the 19th century, and electricity didn’t come to Istanbul until the second half of the 19th century either. The fireplaces and stoves would be cleaned as well as the mangals or braziers – one to each room since there was no central heating.

Since there was no public lighting in the streets of Istanbul and darkness came more quickly during autumn, it was the law that everyone out at night had to carry a lantern of some sort. These, which were made of oil cloth, varied in size depending on the importance of the person. For someone on horseback, it was a large lantern carried by a servant in front of him. A medium-sized lantern signified a person of some means while the smallest lanterns were carried by poor people or those of very modest means. There would also be lanterns at the front gates of the well-to-do. The soft light of candles and lanterns in windows must have made Istanbul seem even more magical than it is today.