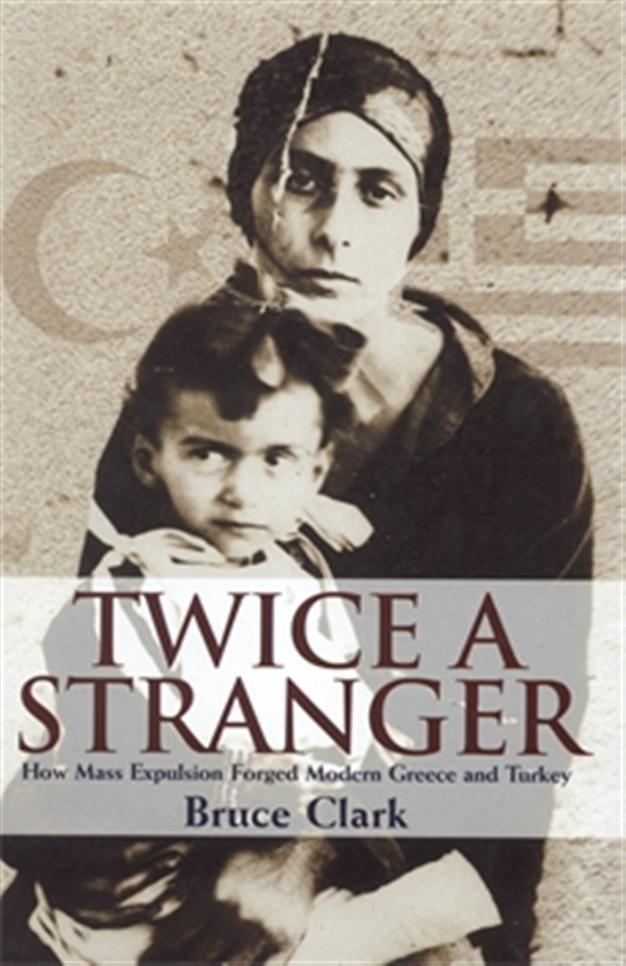

Twice a Stranger: How mass expulsion forged modern Greece and Turkey

William Armstrong - william.armstrong@hdn.com.tr

‘Twice a Stranger: How Mass Expulsion Forged Modern Greece and Turkey’ by Bruce Clark (Granta, 2007, 35TL, pp 274)

‘Twice a Stranger: How Mass Expulsion Forged Modern Greece and Turkey’ by Bruce Clark (Granta, 2007, 35TL, pp 274)The population exchange between Turkey and Greece, agreed in the Swiss lakeside town of Lausanne in January 1923, amounted to one of the greatest population movements of the 20th century. The agreement came as the two states sought to fix their borders after the Turkish War of Independence, and resulted in the obligatory removal of around 1.5 million Greeks from Anatolia and around 500,000 Muslims from Greece. With a few geographical exceptions, anyone who lived in the “wrong” place would be deported from their ancestral homeland across the Aegean to start a new life in the “right” country. It was the logical conclusion of a process through which a chaotically multinational empire gave way - gradually and over many years - to sharply defined and homogenous nation states. Bruce Clark’s “Twice a Stranger” is a compelling look at how this came to be, the practicalities of how the exchange was undertaken, and the legacy that it left. Clark is a journalist who knows both countries intimately, and handles both the historical and the human material with authority and sensitive fair-mindedness. For all the passions that can still arise on either side of the Aegean, it’s hard to imagine how anyone could possibly object to such a scrupulously even-handed book.

Despite the rigid and ostensibly unambiguous division that the population exchange imposed, there are a number of paradoxes at its heart. Not the least of these is the fact that the statesmen of Greece and Turkey at the time were trying to build modern and secular nations in which religion would be less important as an organizing principle; but to do this it was seen as necessary to first gather together people of the same religion and expel those who weren’t. As Clark writes, it was thought that it would be “much easier to create a new, politically and ethnically defined community – a community of Greek citizens, say, or of Turkish citizens – if the ‘raw material’ for each national project was all of the same religion.” Thus, with a few exceptions, orthodox Christians from the Black Sea, the Aegean and across Anatolia - who often didn’t speak a word of the Greek language - were abruptly ordered to leave the lands in which their ancestors had lived for hundreds of years and resettle in their “natural” homeland. The reverse was happening with Turks (apart from those in Western Thrace) in territory controlled by Greece.

It seemed to be a clean, rational solution to the few bloody years of war that put paid to centuries of Greek-Turkish coexistence, but human beings have memories and emotions. So, alongside the historical account, Clark also probes the psychological effects of the population exchange, tracking down the few nonagenarian survivors, (I wonder how many are still alive, as the book was first published six years ago), and mining them for their recollections. While the historical facts are comprehensively researched and cogently presented, it is these interviews that are perhaps the greatest triumph of the book. Clark’s interlocutors display a curious combination of sentimentality and hard-nosed pragmatism; as one representative old man who grew up in a Pontic Greek village on the Black Sea coast lyrically puts it:

The hay smelt of flowers, the milk smelt of flowers, the butter smelt of flowers; all our produce was of high quality thanks to the fodder provided by nature ... But I still feel it was necessary for us to leave. Our only protection in Turkey was the isolation of our village and the good relations which people like my uncle enjoyed with his Turkish colleagues in the bank… I think we did the right thing when we came to Greece.

Almost everyone carries rose-tinted memories of life in the “old country” and the lived experience of a life shared with the “other side” – but, equally, almost all echo the official state view on both sides that the exchange was in the end “necessary.”

The Lausanne agreement provided a depressing recurring template throughout the 20th century. As the book was written and published some years ago, Clark often refers the Greek-Turkish population exchange to the contemporary Balkans, but reading it today it’s impossible not to think of current developments in the Middle East. Whether or not orthodox nation states like Greece and Turkey emerge from the crumbling of the Sykes-Picot arrangement in the region, it seems likely that politically mixed communities are going to be divided on ethnic-sectarian lines. It’s chastening that after almost 100 years, history continues to repeat itself.

Notable recent release

(Stanford University Press, $25, pp 312)