The limits of social engineering in Turkey

William Armstrong - william.armstrong@hdn.com.tr

‘Nation-Building in Modern Turkey: The People’s Houses, the State and the Citizen,’ by Alexandros Lamprou (IB Tauris, 306 pages, £62*)

‘Nation-Building in Modern Turkey: The People’s Houses, the State and the Citizen,’ by Alexandros Lamprou (IB Tauris, 306 pages, £62*)In Turkey it is widely thought that whoever sits in government has the authority to reshape society however they wish. The country’s politicians are encouraged to see themselves as omnipotent Gods molding society like putty. His devoted supporters and bitter opponents don’t agree on much, but many believe that current President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has the power to refashion all of Turkish society on his own religiously conservative lines. When the public is as polarized as it is in Turkey on cultural identity, this leads to an even more hysterical public conversation.

Despite this, there are countless examples from Turkey that demonstrate the limits of state social engineering. The Kemalist nation-building project itself is perhaps the most instructive. The Turkish Republic’s new order after 1923 succeeded in changing many things, but today both sympathizers and critics agree that its achievements were far from complete. Despite the conviction of the single-party regime from 1923 to 1950, Turkey did not Westernize en masse in the way that many hoped.

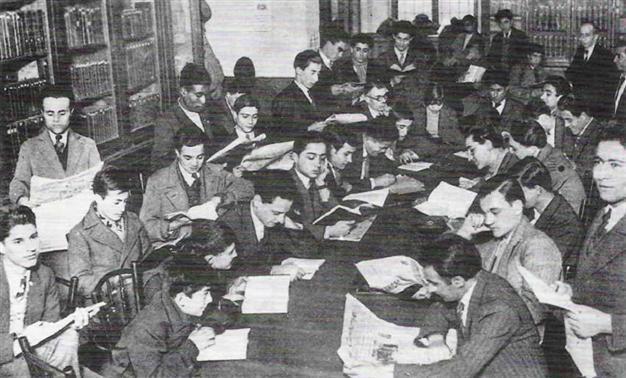

Among the regime’s most significant initiatives were the “Halkevi,” or People’s Houses, which operated in cities and towns across Turkey from 1932 to 1951. Financed by the party-state, their role was to disseminate the official ideology of Turkish nationalism and Westernization to traditional Muslim society. They were part of a top-down project whose explicit goal was to mold a “modern and civilized Turkish nation” through novelties such as sports, cinema, theater, Western music, concerts, and dance parties. In conservative Anatolian towns, the People’s Houses also aimed to promote the novel concept of men and women mixing as fellow citizens. In the words of Republican People’s Party (CHP) Secretary Recep Peker at the time, the aim was to knead “the parts of [the nation] that have come apart due to different accents, levels of civilization and religious sects, into a social body, into the shape of a nation.” Up until their closure, almost 500 People’s Houses were established, becoming one of the most salient symbols of the Kemalist regime.

Among the regime’s most significant initiatives were the “Halkevi,” or People’s Houses, which operated in cities and towns across Turkey from 1932 to 1951. Financed by the party-state, their role was to disseminate the official ideology of Turkish nationalism and Westernization to traditional Muslim society. They were part of a top-down project whose explicit goal was to mold a “modern and civilized Turkish nation” through novelties such as sports, cinema, theater, Western music, concerts, and dance parties. In conservative Anatolian towns, the People’s Houses also aimed to promote the novel concept of men and women mixing as fellow citizens. In the words of Republican People’s Party (CHP) Secretary Recep Peker at the time, the aim was to knead “the parts of [the nation] that have come apart due to different accents, levels of civilization and religious sects, into a social body, into the shape of a nation.” Up until their closure, almost 500 People’s Houses were established, becoming one of the most salient symbols of the Kemalist regime.This book by Alexandros Lamprou, a lecturer at Ankara University, is perhaps the most detailed study of the People’s Houses available in English. In it, he questions the clear-cut notion of the People’s Houses as a homogenous state institution imposed on a passive population. While the Houses were intended by the party-state to present a singular, uniform ideal, reality was far more ambiguous. Whatever the government envisaged, neither the cadre nor the operation of every People’s House across Turkey could be identical. Local sociopolitical and cultural conditions always deeply affected them, challenging the state’s reformist zeal.

Through close study of the People’s Houses in local contexts, Lamprou highlights the center’s limited ability to enforce its ideals. For all the uniformity of their structures and their tight hierarchical control, the People’s Houses had to operate within local societies where uniformity was a desire not a reality. In provincial towns across Turkey, local forces renegotiated, accommodated and adapted the imposition of the People’s Houses. The author describes this as a “domestication” of state policies:

State institutions and officials were not ‘society-proof’ even in places like the Kurdish-populated south-east where the cleavage between state officials and local population was greater and state presence limited … even there locals were able to contest and influence them, and, thus, convert the execution of the center’s plans.

The regime’s ideas - without necessarily being rejected - were inevitably blended with activities, perceptions and practices they were supposed to eradicate.

Both sympathizers and critics of Kemalism imagine a clear-cut border dividing the state from “society.” However, as Lamprou shows in this book, “study of local politics renders the differentiation between an omnipotent and monolithic state or bureaucracy and an equally undifferentiated and potentially hostile society, against which the state operated, quite simplistic.” This results in an “overestimation of the role, power and domination of an omniscient and omnipotent state over a passive society.”

All of this has lessons for today. If state social engineering was limited back in the first half of the 20th century, how much more limited must it be in the Turkey of 2015? Opponents of the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) often claim that it wants to transform Turkey into a theocratic state and cultivate an overwhelmingly pious population. The problem here is not that it assumes the AKP aims for this (many of its members do), but that it assumes any government has the capacity to realize this ambition. That is a big misunderstanding. In an age of rapid change driven by a bewildering combination of forces, the idea that the state is able to significantly remold Turkey’s hugely complex society is a quaint delusion.

It would be complacent to suggest that the state has zero power to affect people’s behavior. Social engineering projects can profoundly affect the lives of citizens for better or worse, but they cannot fundamentally alter the course of history. There are other powerful crosswinds pulling Turkish citizens in directions other than those approved by the center. President Erdoğan may repeatedly exhort parents to have “at least three children” and put in place policies to encourage this. But fertility rates in Turkey continue to decline, marriage rates drop, and divorce rates rise. Whether one deplores or praises these trends, traditional state mechanisms can do little to change them. As a result, the sound and fury of Turkey’s culture war may be little more than a cacophonous but ultimately empty pantomime.

_______

* Hürriyet Daily News readers can order this book from www.ibtauris.com for the special offer price of £20. To claim the discount, enter the code NATIONBUILDING at the checkout stage. Offer valid till June 28, 2015. Customers are responsible for clearing all local import taxes and duties on all orders.