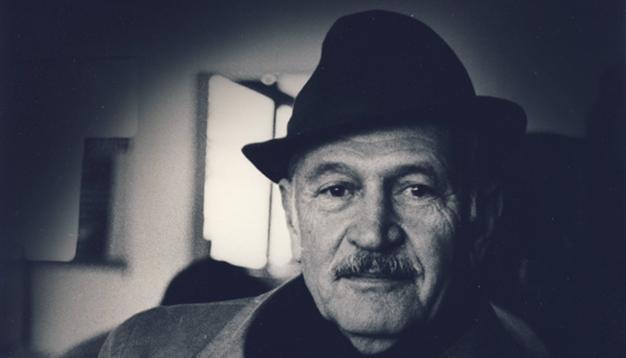

Poems of Oktay Rıfat

William ARMSTRONG - william.armstrong@hdn.com.tr

‘Poems of Oktay Rıfat’ by Oktay Rıfat, trans. Ruth Christie and Richard McKane (Anvill Press, £12, 256 pages)

‘Poems of Oktay Rıfat’ by Oktay Rıfat, trans. Ruth Christie and Richard McKane (Anvill Press, £12, 256 pages)The modernization of Turkish poetry had already been long underway when Oktay Rıfat published the “Garip” (Strange) volume with Orhan Veli and Melih Cevdet Anday in 1941. Nazım Hikmet’s blistering experimentation had been radically reshaping the language of Turkish poetry for almost 20 years, and the “Garip” movement is commonly cited as the second key transformative step against traditional Ottoman literary conventions. As Veli wrote in the selection’s manifesto-like preface, the aim was to eliminate:

all artifice and convention from poetry. Rhyme and metre, metaphor and simile had been devised to appeal to a succession of elites … Today’s poet must write for growing masses. The problem was not to undertake their defense, but to find out what kind of poetry it was that appealed to them, and to give them that poetry.

Actually, this wasn’t hugely different to what Hikmet had been pushing for years, and 1941 is quite late for such a “modernist awakening” anyway, but the “Garip” poets would nevertheless come to be seen as key revolutionaries of 20th century Turkish poetry.

Rıfat’s earliest work shares with Veli a determination to avoid using “pretentious” or “literary” language. Both had a poetic sensibility that prioritized humble, personal reflections on ordinary daily life, elevating it to the level of art. However, after Veli’s premature death in 1950, Rıfat started to develop a more consciously “intellectual” perspective; his novel, unconventional forms becoming more and more cerebral. Reading Veli often feels like encountering a raffish, rakı-chugging “Istanbul man” of the early republican era, but Rıfat is less socially specific. His three formative years in Paris in the 1930s, surrounded by innovators and enthused by the possibilities of surrealism applied to Turkish, seem to have become increasingly important throughout his life.

Rıfat’s earliest work shares with Veli a determination to avoid using “pretentious” or “literary” language. Both had a poetic sensibility that prioritized humble, personal reflections on ordinary daily life, elevating it to the level of art. However, after Veli’s premature death in 1950, Rıfat started to develop a more consciously “intellectual” perspective; his novel, unconventional forms becoming more and more cerebral. Reading Veli often feels like encountering a raffish, rakı-chugging “Istanbul man” of the early republican era, but Rıfat is less socially specific. His three formative years in Paris in the 1930s, surrounded by innovators and enthused by the possibilities of surrealism applied to Turkish, seem to have become increasingly important throughout his life.

Nevertheless, those early years still echoed through Rıfat’s work. In his poem “Umbrella” (1969) it’s possible to detect the spirit of Veli:

I was walking under my umbrella.

It was raining cats and dogs.

Torrents of water either side.

But in my head brightness, sunny days,

Hopes, desires, loves, seas,

I was walking under my umbrella.

Blue sky under my umbrella.

That poem also displays Rıfat’s characteristic use of metaphorical weather. Sometimes he takes that too far, but sometimes it can produce lovely lines, as in his 1973 poem “Pomegranate”:

Prolific once as a pomegranate full of seeds,

What became of you!

…

You were like that happy tree,

A flight of sparrows descending about you.

What became of you!

Now you’ve run out; turned into a waterless mill!

The translation in this volume by Ruth Christie and Richard McKane is unfussy and direct, preferring literalism to interpretation, while the selection itself is slightly over-exhaustive. There’s plenty of chaff that could have been cut out, but the book still gives a good sense of why Rıfat - at his best - deserves his place at the high table of 20th century Turkish poets.

Notable recent release

(I.B. Tauris, £62, 256 pages)

Rıfat’s earliest work shares with Veli a determination to avoid using “pretentious” or “literary” language. Both had a poetic sensibility that prioritized humble, personal reflections on ordinary daily life, elevating it to the level of art. However, after Veli’s premature death in 1950, Rıfat started to develop a more consciously “intellectual” perspective; his novel, unconventional forms becoming more and more cerebral. Reading Veli often feels like encountering a raffish, rakı-chugging “Istanbul man” of the early republican era, but Rıfat is less socially specific. His three formative years in Paris in the 1930s, surrounded by innovators and enthused by the possibilities of surrealism applied to Turkish, seem to have become increasingly important throughout his life.

Rıfat’s earliest work shares with Veli a determination to avoid using “pretentious” or “literary” language. Both had a poetic sensibility that prioritized humble, personal reflections on ordinary daily life, elevating it to the level of art. However, after Veli’s premature death in 1950, Rıfat started to develop a more consciously “intellectual” perspective; his novel, unconventional forms becoming more and more cerebral. Reading Veli often feels like encountering a raffish, rakı-chugging “Istanbul man” of the early republican era, but Rıfat is less socially specific. His three formative years in Paris in the 1930s, surrounded by innovators and enthused by the possibilities of surrealism applied to Turkish, seem to have become increasingly important throughout his life.Nevertheless, those early years still echoed through Rıfat’s work. In his poem “Umbrella” (1969) it’s possible to detect the spirit of Veli:

I was walking under my umbrella.

It was raining cats and dogs.

Torrents of water either side.

But in my head brightness, sunny days,

Hopes, desires, loves, seas,

I was walking under my umbrella.

Blue sky under my umbrella.

That poem also displays Rıfat’s characteristic use of metaphorical weather. Sometimes he takes that too far, but sometimes it can produce lovely lines, as in his 1973 poem “Pomegranate”:

Prolific once as a pomegranate full of seeds,

What became of you!

…

You were like that happy tree,

A flight of sparrows descending about you.

What became of you!

Now you’ve run out; turned into a waterless mill!

The translation in this volume by Ruth Christie and Richard McKane is unfussy and direct, preferring literalism to interpretation, while the selection itself is slightly over-exhaustive. There’s plenty of chaff that could have been cut out, but the book still gives a good sense of why Rıfat - at his best - deserves his place at the high table of 20th century Turkish poets.

Notable recent release

(I.B. Tauris, £62, 256 pages)