‘Motherland Hotel’ by Yusuf Atılgan

William Armstrong - william.armstrong@hdn.com.tr

‘Motherland Hotel’ was adapted into a 1986 film directed by Ömer Kavur, starring Macit Koper (R) in the lead role of Zebercet.

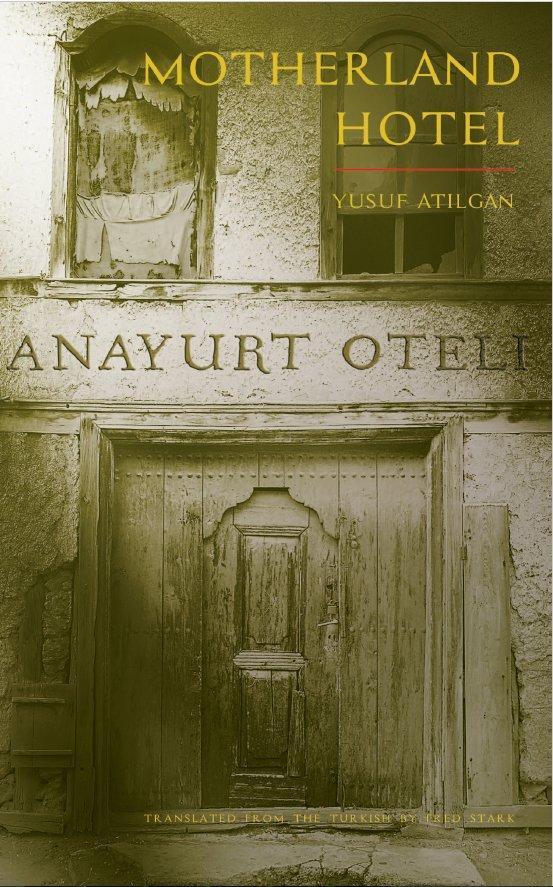

‘Motherland Hotel’ by Yusuf Atılgan, translated by Fred Stark (City Lights, 152 pages, $15.95)“Motherland Hotel” is the only novel by Turkish author Yusuf Atılgan yet translated into English. At barely 150 pages it is a minor masterpiece: The dark story of one man’s descent into madness, convulsed by sexual obsession and social isolation. Atılgan has been compared to Camus and Faulkner, but above all “Motherland Hotel” evokes a kind of Turkish version of The Shining.

The book was published in 1973, and this nimble English translation by the late Fred Stark first appeared in 1977. It has just been republished by City Lights, carrying the kind of Orhan Pamuk jacket quote coveted by every publisher: “I love Yusuf Atilgan; he manages to remain local although he benefits from Faulkner’s works and the Western traditions.”

The book was published in 1973, and this nimble English translation by the late Fred Stark first appeared in 1977. It has just been republished by City Lights, carrying the kind of Orhan Pamuk jacket quote coveted by every publisher: “I love Yusuf Atilgan; he manages to remain local although he benefits from Faulkner’s works and the Western traditions.” The story follows Zebercet, a middle-aged loner who runs a small rundown hotel near a train station in İzmir, inherited from his grandfather. Visitors to the hotel include villagers, tobacco farmers, party delegates, dentists, newly enlisted soldiers, marketplace vendors, livestock dealers, teachers, students, lawyers, prostitutes, touring actors, and one-night couples. Zebercet is “serious and patient” but alienated from society, having no friends and making no visits to the restaurant or cinema. His life follows a mundane daily pattern, structured by daily administrative tasks and routine, passionless sexual liaisons with the hotel maid.

This tedious life is dramatically interrupted by the one-night stay of an alluring woman visiting from the capital, referred to only as “the woman off the Ankara train.” When she leaves in the morning she tells him that she is visiting relatives in the country and will return in one week for another night. Although the woman’s stay is brief and their conversation is minimal, Zebercet quickly becomes obsessed.

He shaves off his mustache and purchases new clothing so he will look his best when she returns. He preserves the room she stayed in shrine-like, periodically creeping into it to masturbate (and more) beside her perceived ghost. He sleeps in the bed, leaves the sheets unchanged, and fondles the sweater and towel she left behind. The novel presents his gradual psychological unraveling with barely a wasted word. Quotidian details are precisely observed and loaded with meaning. A claustrophobic atmosphere is built with unspoken tension and few fireworks.

A week passes without the woman’s return, followed by more weeks and months. Zebercet descends further into obsessive madness and debasement. The woman’s visit triggers traumatic senses just below the surface. We get tantalizing glimpses of a history of familial bad luck, violence and sexual trauma, as the narrative fragments in line with Zebercet’s mental state. The threads that have drawn the novel together are poetically unraveled, as it alternates between traditional narrative fiction and modernist stream-of-consciousness poetry.

Zebercet’s psychic rambling becomes increasingly spectacular, but on the surface “Motherland Hotel” remains introverted and domestic. It was first published during the 1970s and was seen as a statement of artistic integrity at a time of rising political turmoil in Turkey. The novel paints a picture of tragedy in small-town life apparently without political significance. Readers are left to interpret hints of social and political comment as Zebercet’s mind fragments as they wish. Atılgan has the skill to balance the narrative without crudely pushing us in any one direction. As the translator Fred Stark writes in the introduction, it is “not that Motherland Hotel is devoid of political implications, but they are not brandished at the reader.”

Stark tells us that the novel was for a time “required reading for psychiatry students in Ankara’s major hospital-university complex.” It is certainly an intense, audacious book. Its reappearance in English is reason to celebrate.

*Follow the Turkey Book Talk podcast via Twitter, iTunes, Stitcher, Podbean, Acast, or Facebook.