Turkey in 2014: Not too bright

I hope you had a nice entry to this new Gregorian year of ours and now look at the future with some optimism for the dozen months ahead. As a Turkey analyst, however, I can offer only a modest optimism and only if I try really, really hard.

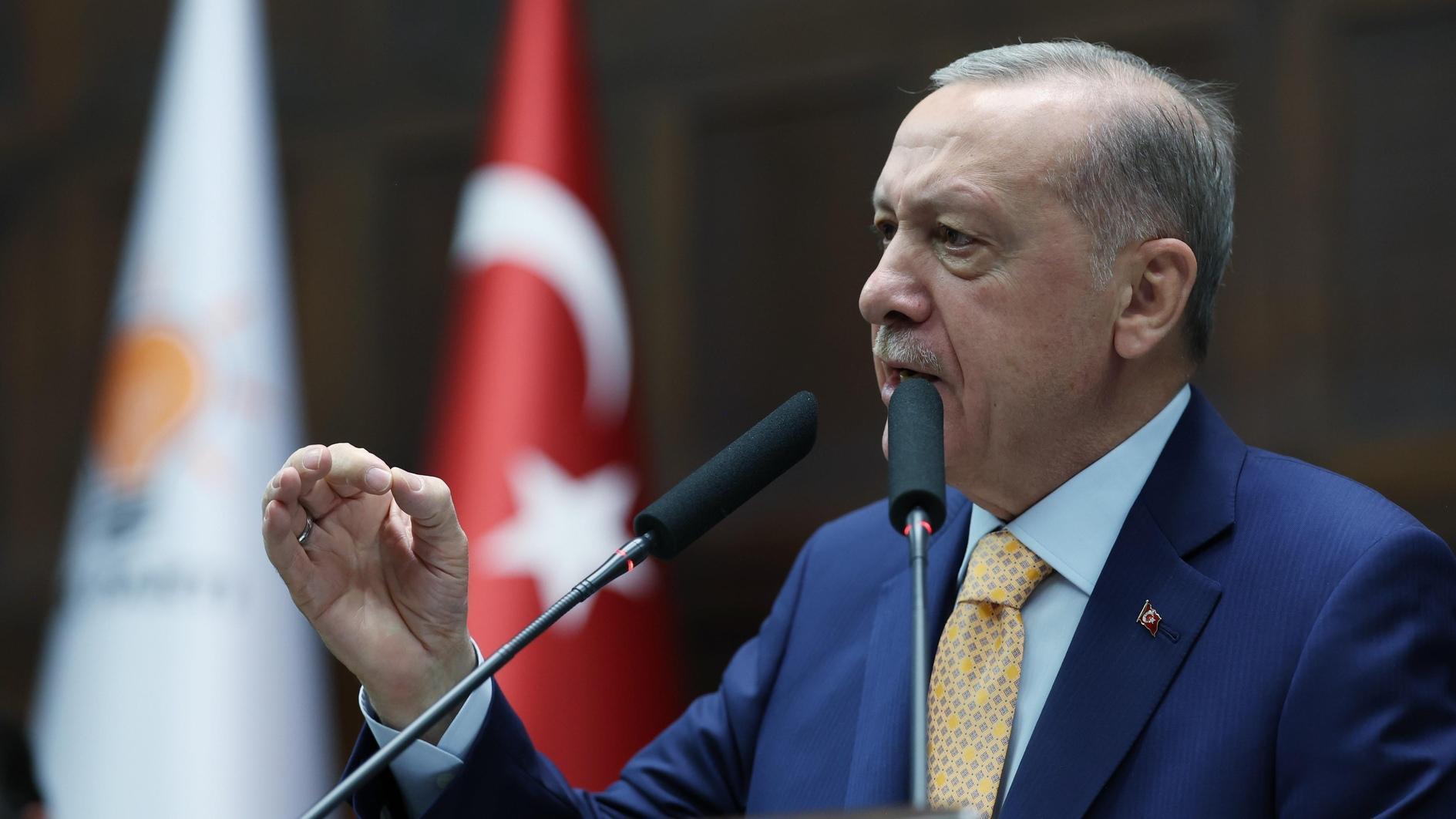

The main reason is the bitter polarization that Turkey inherits from the past year. A part of this comes from Turkey’s long-time fault line: secularists versus religious conservatives. The Gezi Park protests of last summer, at least in part, were a manifestation of how explosive this tension is. Meanwhile, Prime Minister Tayyip Erdoğan’s growingly conservative rhetoric, such as his attempt to intervene in private homes to disallow “girls and boys” from living together, constantly kept the culture war alive.

But there is even more toxic polarization now, the one within religious conservatives, namely the supporters of Prime Minister Erdoğan and Islamic scholar Fethullah Gülen. The tension between these former allies grew out of the Gülen Movement’s presence in the police and judiciary, real or perceived, and recently turned into a war of words and a legal battle. The movement supports the corruption investigation that targets some cabinet members, whereas the government depicts the same investigation as a veiled “coup attempt” cooked up by “foreign powers.” The same official narrative openly condemns the Gülen Movement as the fifth column of those “foreign powers,” which are, typically, the CIA, neo-cons, the Israeli lobby, and Israel.

This conspiratorial mind is poisonous enough for the political atmosphere, but there are worrying signs that the worst is yet to come. On Monday, Abdurrahman Dilipak, a famous columnist for Yeni Akit, a hardcore Islamist daily, wrote that the government might soon initiate an extensive purge against the Gülen Movement. “Do not be surprised,” he said, “if all actors in this scenario, such as policemen, prosecutors, judges, businessmen, journalists are put on trial.”

As I have written before, if there are bureaucrats who misuse their authority to serve the interest of the Gülen Movement, or any other entity, the government certainly has the right to fire them and bring them to justice. However, what Dilipak describes is a much larger scale witch-hunt, which can only violate many civil liberties and raise the tension in society to new heights.

Based on such ill omens, I predict that 2014 might be a very tense year. The government’s claim to fight a “new war of independence” against imaginary enemies that conspire against Turkey only signals more authoritarianism and less freedom.

The two subsequent elections of this year might possibly further raise this tension, but perhaps diffuse them as well, based on the results. The local elections of March 30 are crucial, for it will be the first test of Erdoğan’s popularity after Gezi and the confrontation with the Gülen Movement. If the governing party loses a considerable amount of votes, then Erdoğan might rethink running for presidency in the presidential elections of June, which will be a first in republican history. If the government rather gets a boost in the ballots, more intoxication with power might follow.

The sad truth is that Turkey, which was shown until a few years as a “model” of liberal democracy in a Muslim-majority country, looks anything but liberal now. It apparently will go through some serious headaches before deserving to be counted as a mature democracy.