Sorry seems to be the hardest word

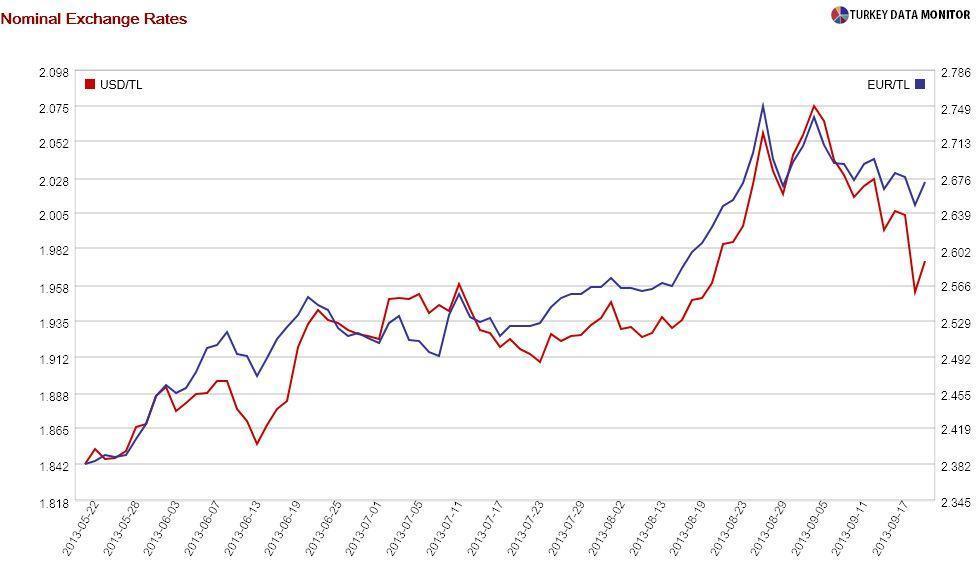

When the Turkish Lira quickly appreciated from around 2 to 1.95 against the dollar on the morning of September 19 after the Fed’s surprise decision to postpone tapering its bond purchases, I got an email from a staunch supporter of the Central Bank of Turkey’s policies.

When the Turkish Lira quickly appreciated from around 2 to 1.95 against the dollar on the morning of September 19 after the Fed’s surprise decision to postpone tapering its bond purchases, I got an email from a staunch supporter of the Central Bank of Turkey’s policies.She was arguing that since Governor Erdem Başçı had successfully predicted not only the tapering delay but also that Larry Summers would not be the Fed’s next chairman, I and die-hard critics of Turkish monetary policy should apologize. I am good at neither giving nor taking apologies, so I’ll offer an explanation instead.

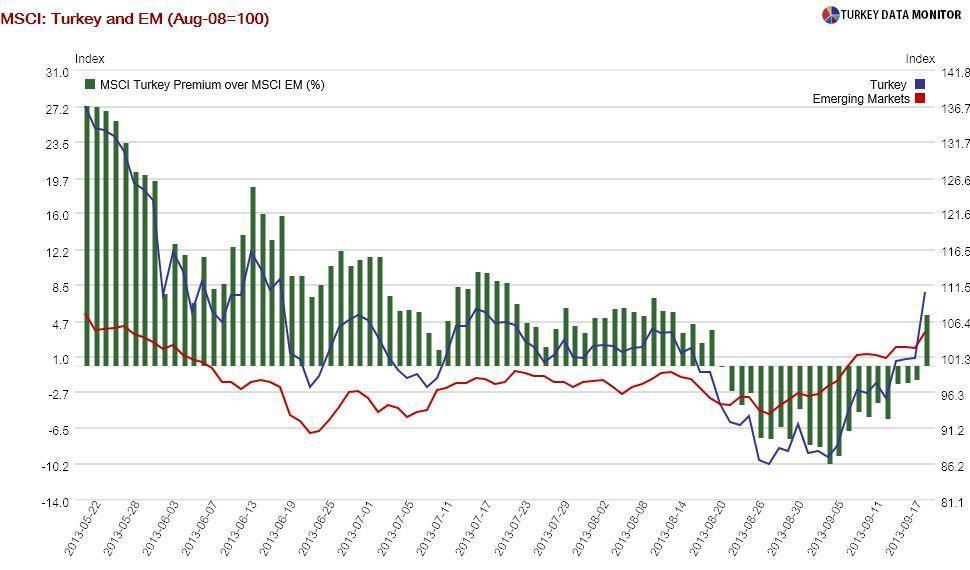

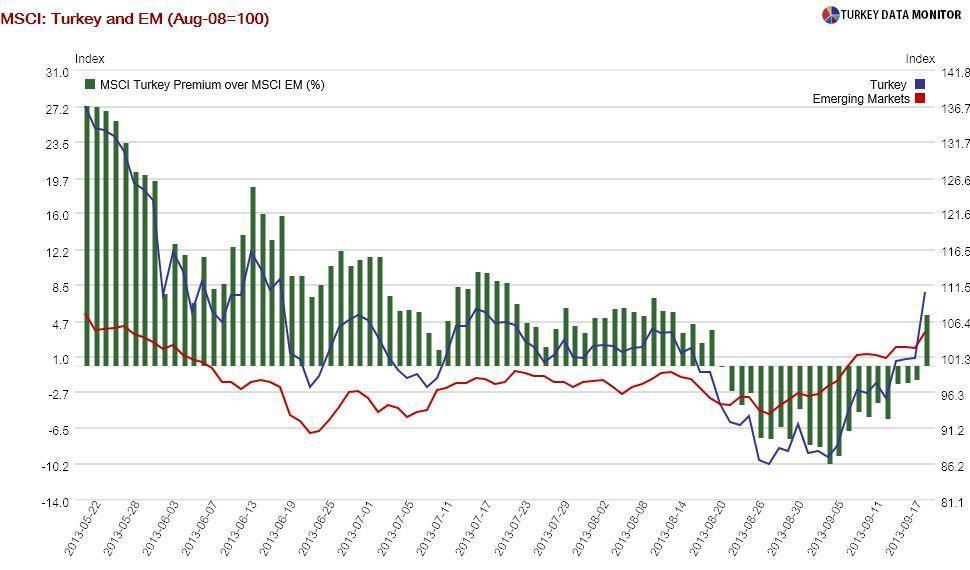

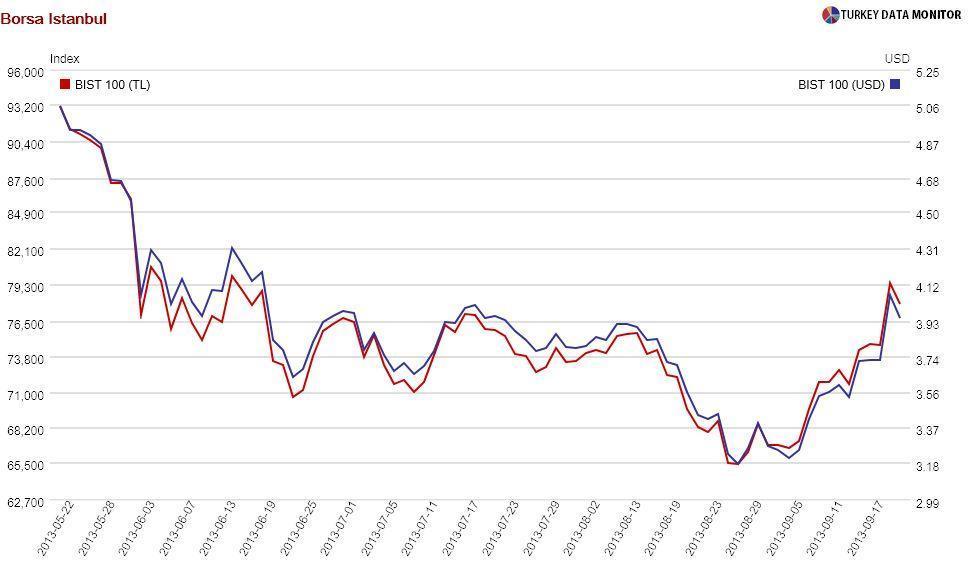

Emerging market (EM) assets were already on the rise after the former Treasury secretary announced Sunday night, Turkish time, fearing opposition from key Democrats, that he was withdrawing his Fed candidacy. Turkish assets perform better than most EM peers in good times, but underperform in bad times. Last week was no exception.

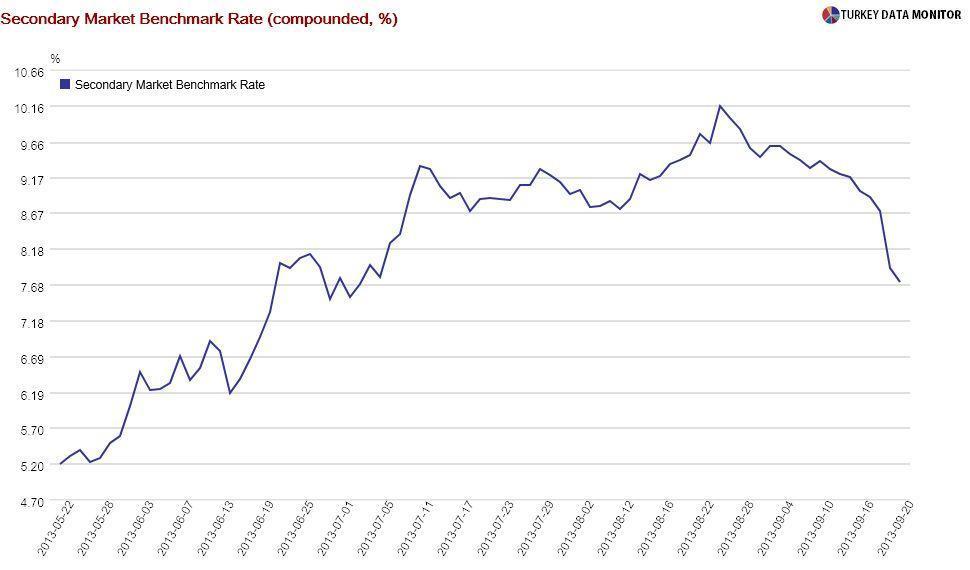

Take the yield on the Turkish two-year government benchmark bond. After decreasing from 9.2 to below 9 percent following the Summers announcement, it continued to fall. It then plunged after the Fed decision, dropping below 8 percent. Even the pause to the global markets rally on September 21 could not hold it back, as it ended the week at 7.8 percent.

According to Goldman Sachs, the rally in Turkish bonds could continue. The bank’s economists try to find out the maximum response of EM assets to Fed policy surprises by using a statistical technique called vector autoregressions (VARs), which is sort of like gumbo soup: You look at the relationship between a bunch of variables without specifying a structural model.

Goldman researchers discover that even though Turkish bonds showed the strongest response to the Fed’s surprise, they have the most room to go after their Russian, Brazilian and Indonesian counterparts. All three rallied less than Turkish bonds on September 19. On the contrary, Turkish equities attained their maximum response that day, as they outperformed peers by far.

Most surprisingly, despite having the best performance after the Brazilian real and Indonesian rupiah, the lira has the most room to go along with the Hungarian forint and the South African rand. It lost some of its gains on September 20, and so the case for long-run lira appreciation is still valid. It could even reach Başçı’s end-year target of 1.92 against the dollar soon.

It’s getting more and more absurd. Goldman economists find that the biggest reactions to Fed surprises come from countries that rely on external financing the most. That’s the government’s doing. But Turkish assets’ maximum responses to U.S. monetary policy shocks are much larger than countries with similar current account deficits. Blame it on the rain – not the Central Bank.

The other side of the coin is that Turkish assets would underperform during negative Fed surprises. It’s indeed a sad, sad situation, and I wonder whether “sorry” will be enough once we are hit with another negative Fed shock.