Lessons from the fall of the Wall for Turkey

If you fell into a coma in East Germany in October 1989 and woke up a few months later - like the protagonist’s mother in the German movie “Good Bye Lenin!” - you would find yourself in a completely different country.

If you fell into a coma in East Germany in October 1989 and woke up a few months later - like the protagonist’s mother in the German movie “Good Bye Lenin!” - you would find yourself in a completely different country.The fall of the Berlin Wall 25 years ago yesterday started the rapid transition from communism and central planning to democracy and market-based economies, not only in Germany but all of Central and Eastern Europe as well as Russia.

At first look, the economic transition does not seem to have been a complete success: The region has grown just 1 percent annually. But that number is misleading: All these countries went through a deep recession early on because of the painful initial adjustments. Besides, there has been a huge divergence in growth performance. Poland’s GDP more than doubled, and whereas the rest of Central Europe did reasonably well, ex-Soviet states lagged behind.

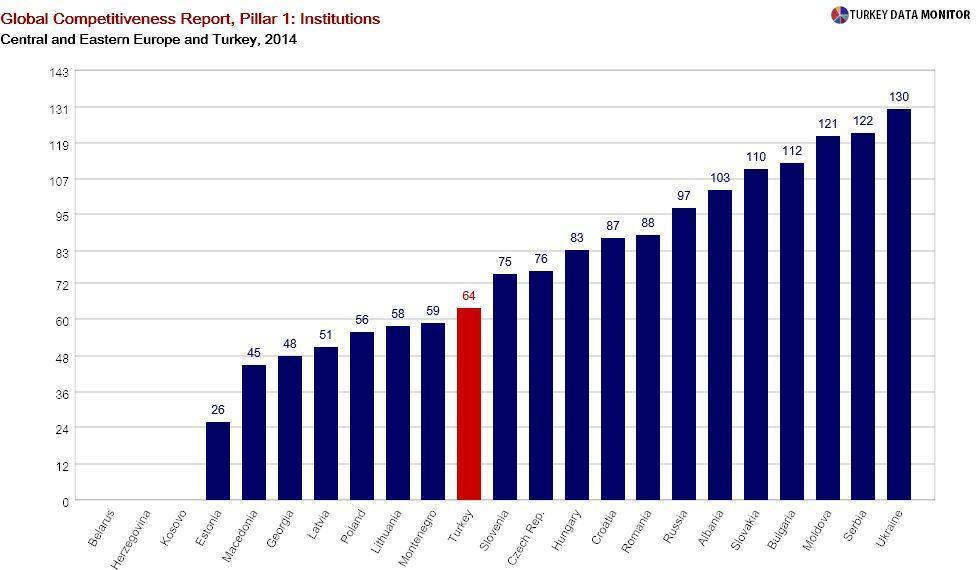

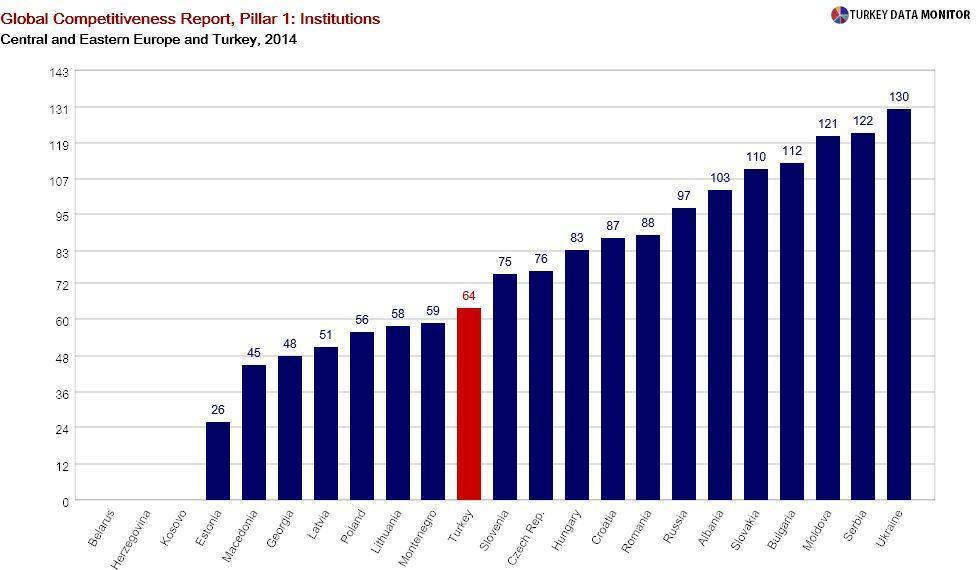

In a recent research note, analysts at economics research firm Capital Economics try to explain this divergence. They argue that, other than different starting points of countries, the speed of reforms and degree of entrenchment of the old system were important. But they suspect that much of the difference in economic performance could be explained by the degree of institutional reform.

There may be lessons for Turkey from the Iron Curtain’s transformation. Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoğlu unveiled nine of the 25 transformation programs of the government’s ambitious structural reform strategy on Nov. 6. There are some things to like about the program, such as the main principles guiding it: The relationship between political stability and economic predictability, human-focused development, adjusting to and leading changes in production technology, integrity in economic policies and full integration to the world economy.

Economists were indeed quite positive. As the perennial pessimist, I, on the other hand, found many things to criticize. If nothing else, the macroeconomic targets of the plan are inconsistent with the Medium-Term Program, which was published only four weeks ago. For example, while the latter envisages GDP to increase to $971 billion in 2017, the former’s 2018 GDP target is $1.3 trillion.

Besides, whereas the programs themselves have well-defined targets, it is not clear how the 417 action plans constituting them will be implemented. Many contain a version of the quintessential Turkish bureaucratic phrase, “gereği yapılacaktır,” which roughly translates as “whatever it takes.” There are vague timetables that seem to be there just for show, and it is not clear how monitoring will be done.

But more importantly, the institutions needed to support this ambitious agenda are not addressed. A program that will be revealed later on is titled “Improving the Business and Investment Climate,” but this just establishes that policymakers have not thought much about prioritization and the links between different reform areas, instead coming out with a grocery list.

In fact, I wouldn’t even call the declaration a reform agenda. At best, it is a wish list showing the government’s willingness to reform. But without a coherent strategy making use of other countries’ experiences, it is bound for failure.