Morsi fails to prevent street fights between Egyptian police, ultras

James M. Dorsey ISTANBUL - Hürriyet Daily News

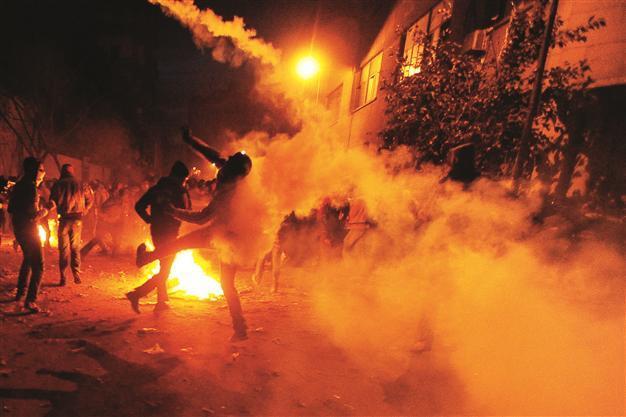

An Egyptian protester throws back a tear gas canister at security forces during clashes in the wake of the Port Said incidents in this file photo from Feb 3, 2012. EPA Photo

A pledge by Egyptian President Mohamed Morsi to re-open all cases against those responsible for attacks on anti-Mubarak and anti-military protesters over the past 21 months has done little to prevent militant football fans from joining the outpour of anger against the president’s unilateral decision to grab wide-ranging powers. The fans are clamoring for justice for the hundreds of dead protesters, including 74 of their own members.Mr. Morsi had hoped that the re-opening of cases, which largely failed to condemn those responsible for repeated crackdowns on protesters, would soften the blow of his power grab and would prevent the militant, highly politicized, street battle-hardened football fans from taking to the streets. The fans, or “ultras,” one of Egypt’s largest civic groups after Mr. Morsi’s Muslim Brotherhood, played a key role in last year’s toppling of former president Hosni Mubarak, and subsequently emerged as the most militant opposition to the military that led Egypt to the election last July which brought Mr. Morsi to power.

The fans’ threat to disrupt football matches has prevented the lifting of the 10-month suspension of professional football, which was imposed in February after 74 supporters of Cairo club Al-Ahly SC died in a politically loaded brawl in the Suez Canal city of Port Said. More than 70 people, including nine mid-level security officials, are on trial in Cairo for their role in the worst incident in Egyptian sporting history, in a slow-moving legal process.

The ultras have insisted that they will prevent a lifting of the suspension for as long as justice for the 74 has not been served. The outpouring of public anger against Mr. Morsi’s recent power grab offered them an opportunity to press their demands for reform of the security forces, an end to corruption in Egyptian football.

It also gave the ultras a renewed opportunity to confront law enforcement. In a replay on the anniversary of battles last year that lasted several days on Mohammed Mahmoud Street, near Cairo’s Tahrir Square, in which 42 people were killed and more than 1,000 wounded, hundreds of ultras have been fighting the police and security forces on that same street for the past five days.

Thousands of ultras joined mass protests against Mr. Morsi’s power grab last week on Cairo’s Tahrir Square, chanting “The people want to topple the regime,” “Do not be afraid, Morsi has to leave,” and “Down with Mohamed Morsi Mubarak.” Hundreds more ultras confronted the security forces on Mohammed Mahmoud and Qasr al-Aini Street with rocks and Molotov cocktails.

Battle for dignity

Ahmed Mounir, 15, told Ahram Online that his brother had been injured in last year’s Mohamed Mahmoud clashes, and had to have a leg amputated. “I have been in the square for three days now. I want to secure my brother’s rights and I don’t care if I live or die,” Mr. Mounir said.

His battle and that of his fellow ultras is a battle for “karama,” or dignity. Their dignity is vested in their ability to stand up to the “dakhliya,” the interior ministry that controls the police and the security forces, as well as the knowledge that they no longer can be abused by security forces without recourse and the fact that they no longer have to pay off each and every policemen to stay out of trouble.

In doing so, the ultras build on the perception of the security forces’ arbitrary use of force, perpetuated by repression in popular neighborhoods and in stadiums. In the words of scholars Eduardo P. Archetti and Romero Amilcar, police and security forces’ “use of physical force aided by arms of some kind … [was] exclusively destined to harm, wound, injure, or, in some cases, kill other persons, and was not used as an act intended to stop unlawful behavior that is taking place or may take place.”

‘Aura of omnipotence’

Official foot-dragging in holding security officers accountable adds to that perception, giving police power and “the aura of omnipotence” despite having “lost all legitimacy both in moral and social terms.” This development has been reinforced in post-revolt Arab societies such as Egypt by the failure to date to reform the security forces. “To resist and attack the police force is thus seen as morally justified,” they wrote.

The renewed clashes on Mohammed Mahmoud Street are as much a protest against Mr. Morsi’s recent power-grabbing constitutional decree as they are about highlighting frustration at Mr. Morsi’s failure to address the urgent need for reform of the police and the security forces.

Without such reforms, violent street protests are likely to erupt on every occasion that offers itself, such as happened during recent protests in front of the U.S. embassy in Cairo against the American-made anti-Muslim video clip. Those protests led in the Libyan city of Benghazi to the death of the U.S. ambassador and three other U.S. officials. Reform of the police and security forces would open the path to Egypt’s return to post-revolt normalcy. It would also allow for a lifting of the ban on professional football, a signal of the return of the calm needed for Egypt to embark on the road to economic recovery.